Oct. 20, 2021

New study aims for early detection of autism to help patients thrive

Understanding humans’ genetic makeup is at the center of a $3.5 million project led by VCU School of Pharmacy researchers.

Share this story

In a search for the keys to autism, researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University are about to begin one of the largest and most thorough scans of the set of chemical instructions, the methylome, that regulates the activity of human genes.

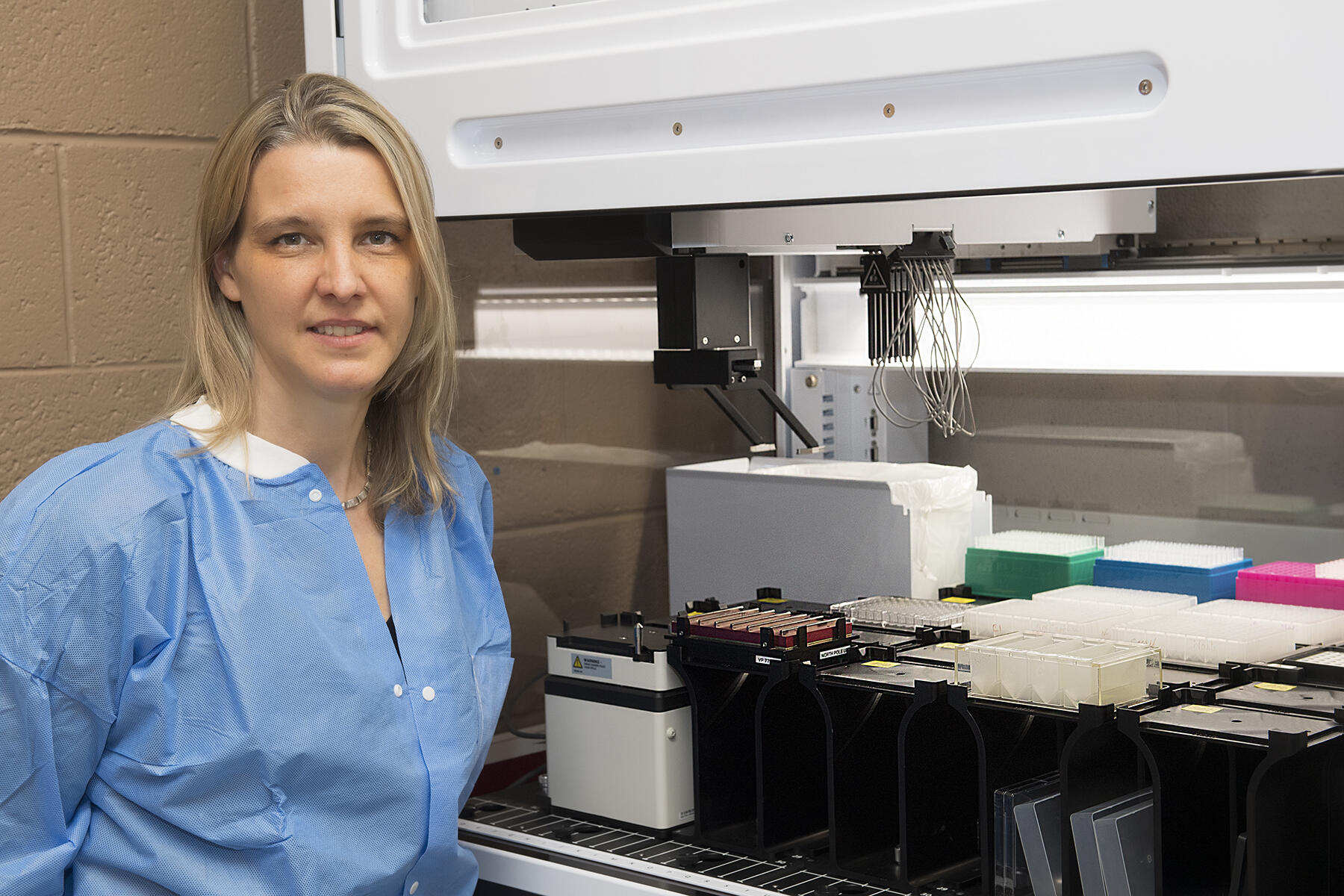

The goal is to identify infants who have high risk of developing the disorder so they can receive early care that could help them thrive, said researcher Karolina Aberg, Ph.D., an associate professor at VCU School of Pharmacy’s Center for Biomarker Research and Precision Medicine and co-director of the VCU Genomics Core.

Aberg and her research partner in the project, Edwin van den Oord, Ph.D., a professor at the School of Pharmacy and director of the Center for Biomarker Research and Precision Medicine at VCU, recently received a $3.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to support the research.

The project, a collaboration with scientists from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, will begin by scanning blood samples from people with and without autism, provided by volunteers in a project managed in Sweden. The samples are paired — one had been taken from newborns, the second from the same people later in life after their autism diagnoses.

By surveying both sets of blood samples, the researchers hope to identify locations where those chemical instructions of people with autism seem different from those of people without autism. The methylome orchestrates whether specific genes are made active and if the activity is turned down, turned up or turned off entirely.

This is of particular interest because each person’s methylomic profile is influenced by genetics and environmental factors and changes over time.

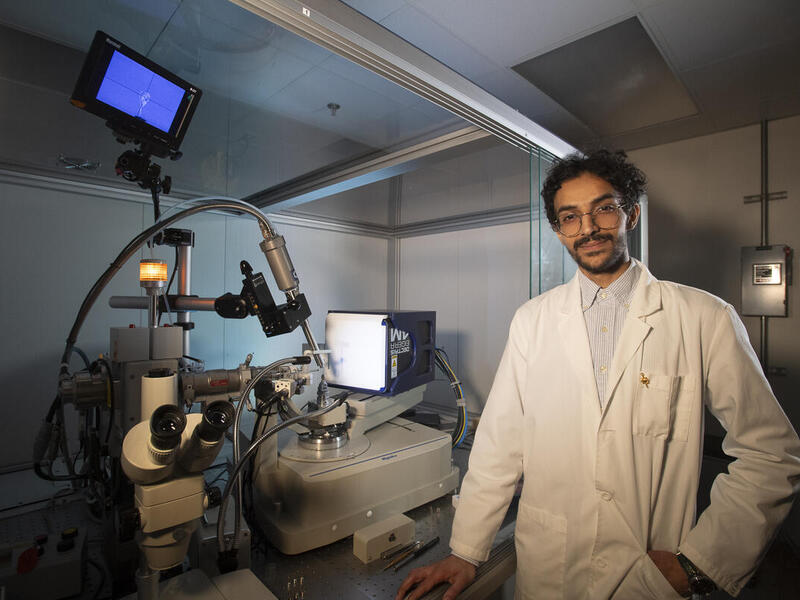

After using sophisticated robotics to prepare the samples, the researchers plan to comb through 28 million separate locations on each sample with a sequencing technology called MBD-seq that detects the locations in the genomic sequence where methylation marks are present or absent.

This careful investigation is much more thorough than previous methylation scans of autism, which typically examine 450,000 sites — about 3% of the human methylome. The VCU project will examine almost 100%.

“It is like the difference between using a flashlight and using floodlights,” Aberg said. “We will be able to investigate a much larger portion of the methylome.”

The process begins by extracting DNA from the blood samples, which arrive as dried blood on paper. The DNA then is cut into fragments.

The shards of DNA that contain methylation sites are “tagged” through an ingenious procedure that attaches minuscule metal beads — so small that 25,000 of them could be lined up inside an inch — that are covered in a protein coating that attaches to the methylation sites. The process then uses magnets to separate these fragments from the rest. The tagged fragments are sequenced, or placed in order, to determine which gene they potentially will regulate.

In a final phase, the researchers will use a similar technique to examine brain tissue of donors with autism to see what methylation profiles and gene expressions can be found there.

“We will see if the methylation profiles look the same in the blood and in the brain,” Aberg said. “If so, we will directly study which genes in the brain are regulated by the methylation profiles.” This is important, she added, because “autism is a disorder mainly involving the brain.”

Aberg emphasized that all blood samples have been provided by volunteers in Sweden who remain anonymous and can withdraw from the research at any time. The brain samples are from anonymous people in the U.S., half of whom had been diagnosed with autism, who donated their bodies after death to support scientific research.

The entire process of studying the samples, including the complex statistical analysis required to identify meaningful methylation sites, is expected to take about five years.

“We hope this study will help autism patients and their families receive the care that will help them thrive,” Aberg said.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.