March 4, 2022

‘Transnational nomadic lifestyle’ inspires alum’s award-winning work

Share this story

Cecilia Hankyeol Kim is from Korea. And England. And Australia and Singapore.

Her Korean family, headed by her expat father, lived a nomadic life, so as a child she resided in each country for only two to four years before moving on to the next.

“As a result, I am adept at adapting and assimilating to a new place very quickly,” said Kim, who received her MFA in photography and film from Virginia Commonwealth University last year and is now an adjunct instructor in the School of the Arts. “I came to appreciate this experience only [recently], as during those years I resented that I couldn’t settle down anywhere. It was a little devastating to arrive at a new place knowing that it was inevitable to leave again.”

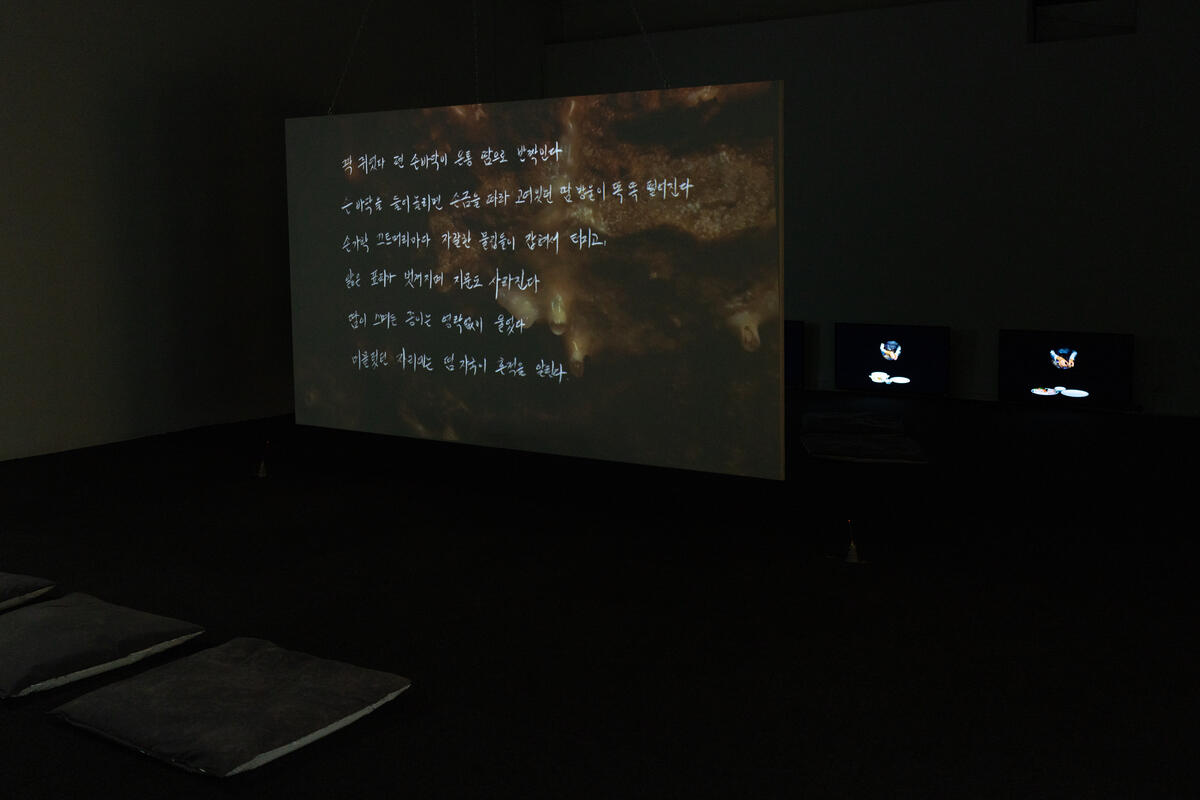

As an artist, that migratory lifestyle heavily influenced her practice. “A lot of my work is about navigating identity and constructing one’s own sense of belonging,” she said. “My videos tell stories through voices and words. Through the language of others, you relate and reflect on yourself. Much of my work is specifically about being a Korean woman who has lived more time outside than within my home country.”

Impressive run of success

Kim’s work with spaces of “otherness” has earned her a number of prestigious residencies, awards and exhibitions.

She is a 2021-23 fellow of the Hamiltonian Artists, an innovative career incubator program for emerging visual artists, and the 2021 Trawick Prize Best in Show winner. The juried Trawick competition and exhibition was established in 2003, with the top winner receiving $10,000.

Winning the Trawick Prize was a complete surprise, Kim said, but it gave her a lot of hope for the future of video art. She was the only finalist whose main medium was video.

“Being a video artist doesn’t earn me a lot of income, and I would have struggled to get by last year if it wasn’t for the award winnings,” she said. “I spent some of the money to travel and shoot my thesis film last year.”

Outside the isolation of the painting studio

Ironically, Kim was never interested in photography and film.

“In fact, I don’t think I had any real talent for it,” she said. “As far as I can remember, I wanted to be a book illustrator and writer, and went into a painting program as an undergrad.” But as a sophomore at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, she took a moving-image class and liked that the medium allowed so much freedom.

“I was initially attracted by the novelty because I have never made videos before,” she said. “I liked that you could make work while being an active member in society, outside the isolation of the painting studio, and that at times it was necessary to collaborate with my friends and family. For me, video was a medium for this kind of interpersonal connection.”

Kim’s multichannel installations use varying zones of sound, multiple immersive video projections and components from domestic spaces to move viewers through her installations, said Jon-Phillip Sheridan, chair of the VCU Department of Photography and Film.

“Her focus is on dramatizing simple food material and everyday acts and exchanges of love and care from the domestic space, and using them as a lens to examine the larger cultural implications — what they reveal and obscure about Korean culture and Korean culture in the diaspora,” he said.

Creating space for a wide range of cultural voices

The 2019 release of Bong Joon-Ho’s “Parasite” garnered a lot of attention for Korean films. It was then that Kim noticed that non-Asians were taking interest in previously released films that were already successful in the East.

She created a course at VCU to share the rich history and astounding films made in the past few decades in East Asia.

“It is important to study and analyze films as artists and filmmakers ourselves,” she said. “I realized immediately when I came to VCU [as a student] that there weren’t any classes devoted to non-Western studies of film in the photography and film program, and wanted to focus specifically on East Asian films, which I am passionate about.”

The class is structured around a selection of films with an overview of their social and political context in the countries in which they were made. Now teaching it for the second semester, Kim has noticed that the film history class comprises the most diverse group of students she’s seen in a single class.

They come from a wide range of cultural backgrounds, Kim said, contributing insights from their own cultures.

“It has been really incredible that this class is creating space for these voices,” she said. “I think it is popular not only because of the recent successes of Asian films like ‘Parasite,’ but I actually think that many of these students have already had a passion for Asian films by filmmakers like Ang Lee and Wong Kar Wai, and it has taken until now for a class to be devoted to them.”

Universal language

Kim is preparing for her next undertaking — an ambitious film project that will take her across the United States to sites of labor, such as factories that manufacture Korean food products, immigrant families making such foods at home, and geological sites such as salt mines and salt flats that relate to this circulation of transnational labor.

The project reaches back to her documentary roots and her passion for film as a means to connect and meet people.

“I was mentally dependent on my art as a therapeutic method of self-healing as I constantly reassimilated into new countries and cities,” she said of her youth. “Art continued to be a consolation to me, a universal language. Art was always an outlet where I could indirectly express myself without words.

“Sometimes I wonder what my life would look like now if I hadn't moved around so much, but the transnational nomadic lifestyle is so embedded and definitive of who I am now. I like to think it gives me a sense of liberation to have an abstract idea of my origins and home, but not be physically bound to geographical location. This identity, of course, is the basis of my art practice.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.