Nov. 22, 2022

Food for thought

Share this story

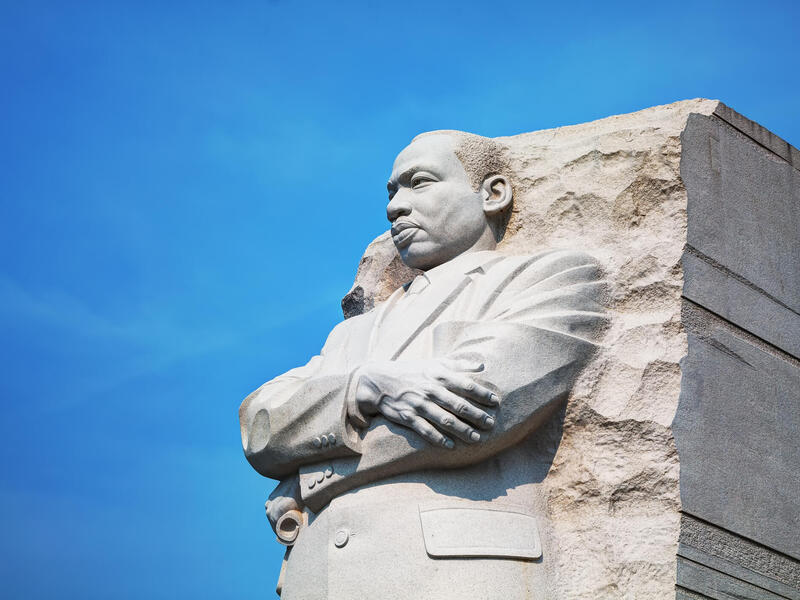

Professor John Jones, Ph.D., knows firsthand what it’s like living with hunger growing up, and that’s why he’s passionate about addressing food insecurity on the Virginia Commonwealth University campus.

“I grew up in poverty. I was on food stamps and Section 8 housing. I was food insecure in college. The very end of my freshman year I used the last money I had to buy day-old bread from Jimmy Johns. Food insecurity impacted my ability to learn and to go to class. It was very frustrating to me,” said Jones, an assistant professor in the Center for Environmental Studies, and a member of the Sustainable Food Access Core in VCU’s Institute for Inclusion, Inquiry, and Innovation (iCubed).

In his Urban Food Production class, students grow microgreens, seedling versions of vegetables that can be harvested 10 days after they are planted.

“They are nutritionally very dense from a micronutrient perspective,” Jones said. “Everything we harvest goes to the Ram Pantry [VCU’s student food pantry]. That was our focus when we came up with this. A lot of the food in the pantry is canned goods or dry goods. We wanted to get as much produce in as possible.”

Food insecurity for students in kindergarten through 12th grade is addressed through school lunch programs, but there are very few programs for college students, Jones said.

“Lunch programs for K-12 students have been very well received around the country. People recognize the value,” he said. “But, there is an assumption that when a young person turns 18 and goes to college, any of the poverty they may have been dealing with growing up is not a problem for them now. That is a massive disconnect.”

Food insecurity is a significant problem in the U.S. and affects people of all ages. The lack of consistent access to food has a negative impact beyond the obvious one of hunger. It can lead to negative physical and psychological health outcomes and mean choosing between food and paying utility bills or, in the case of VCU students, being able to afford books for college courses. According to the USDA, nearly 34 million Americans lived in food-insecure households in 2021.

Professors like Jones, along with staff, students, researchers and health care providers from a range of disciplines across VCU and VCU Health are working to eliminate food insecurity, whether it’s providing food right here on campus or trying to eradicate food deserts in the larger community. VCU News caught up with some of these food insecurity fighters to learn about recent efforts and how they are moving the needle.

Close to home

Youngmi Kim, Ph.D., associate professor in the School of Social Work, is a Sustainable Food Access core member whose research interests primarily focus on food insecurity from an economic perspective. In 2020, she collected data on VCU student food insecurity with an internal grant from the School of Social Work.

The three published studies that resulted from the grant addressed the prevalence of student food insecurity, challenges associated with food insecurity and how students cope with those challenges.

“College food insecurity issues are emerging concerns across the nation, but we did not have much information on our own VCU students. My studies helped better understand their challenges from our students’ lived experiences and inform future initiatives,” Kim said.

Kim’s survey estimates that 35% of VCU students experienced food insecurity before and after the pandemic. “This finding is fairly consistent with stats from [other] public/state college students. One surprising finding was that while 26% of students identified as food insecure at both periods before and after the pandemic, food insecurity tends to be transient over time for almost 20% of students. In other words, students may be exposed to the risk on and off repeatedly,” she said.

Her findings illustrate that the college environment creates or exacerbates many challenges to food security, including limited funds, co-occurring basic needs insecurity, lack of transportation, lack of access to a kitchen and lack of time to prepare meals. When students are experiencing constant competing demands on their time and/or when they have limited financial resources, food is an easy thing to cut out or reduce, Kim said.

“College students are young adults, and they think they can compromise temporarily. But, that is harmful for your health, mental health and academic success,” she said.

Making sure students have the food they need

Ram Pantry started in 2015 to provide in-need VCU students with food. It works to ensure that no student in the VCU community goes hungry and that every student has access to nutritious food.

Recently, the pantry has experienced an increased demand for food among students.

“This semester, we have had record numbers in regards to the number of visits and guests,” said Lisa Mathews-Ailsworth, assistant director for student support in the Division of Student Affairs, who oversees Ram Pantry. “On average, we are having upwards of 80 people visit a week, which is double what we were seeing last year. This semester we’ve served 268 guests over 830 times.”

VCU, the VCU Foundation and Feed More recently entered into a new collaboration enabling VCU to stock its Ram Pantry and the Little Ram Pantries pilot project with nutritious food at discounted prices.

“Our partnership with Feed More allows us to reach more students with more nutritious food options,” said Jones, who is leading the Little Ram Pantries project.

The collaboration will support the university’s ongoing efforts to address food insecurity among its students. Previously, all of the food provided by Ram Pantry and the 13 Little Ram Pantries located on both campuses was directly donated by individuals, organizations and corporations, either directly or through monetary donations. No university funds have been used to purchase food. Through the partnership with Feed More, donations to the VCU Foundation can be leveraged to acquire food from Feed More in an economically sustainable manner.

Additionally, the VCU Monroe Park Campus Learning Garden continues to donate all produce grown in the garden to Ram Pantry. The produce is grown using organic methods, and students, faculty, staff and community members can participate in volunteer activities at the garden to support sustainable vegetable production.

Jones is seeing significant use of the Little Ram Pantries that were installed last fall on VCU’s Monroe Park Campus. Students used the boxes, which are similar to the concept of Little Free Libraries, roughly 75 times per week.

“Our overall objective is to test the potential of our pilot program to mitigate food insecurity for our students,” Jones said. “People that need food can get it.”

Food and health in the community

Across the U.S., millions of people are regularly forced to choose between spending money on food and medicine or heat, electricity, rent and medical care. That’s the case for many residents of the City of Richmond’s East End who are experiencing food insecurity.

Located at the corner of Nine Mile Road and North 25th Street, the VCU Health Hub at 25th offers a variety of resources and programs to help East End residents by connecting them with community providers and helping with care coordination.

As a partnership between VCU and VCU Health, all Health Hub programs are free and delivered by VCU faculty, VCU and VCU Health staff and students, community partners and Richmond Health and Wellness, a program in the School of Nursing. Through the Health Hub, RHWP partners with Sholom Farms to provide prescription produce, an effort that allows physicians to prescribe fruits and vegetables for their patients.

“Food insecurity is a striking issue that affects other health issues. It’s one of the most frequent issues we are engaged with,” said Rich Killingsworth, executive director of the Health Hub at 25th. “This time of year, we see sad evidence that this is a worsening issue. The holidays put a financial constraint on families, which causes more need.”

People who come to the Hub are “almost embarrassed to say I am hungry,” said Stephanie Flowers, who works at the Hub as a community health worker/outreach coordinator. “People can come in presenting symptoms as one thing but by the time they leave we tap into the fact they need several resources for food insecurity.”

A couple of months ago, Flowers worked with a woman who came in to get resources for domestic violence and discovered she didn’t have the food she needed to sustain her. She also needed help with money for medications.

“It comes down to, ‘Do I buy processed foods or fresh fruits or vegetables? Do I get medications or do I get food?’ Ninety percent of the people that use our services are geriatric. They don’t have a lot of extra income,” Flowers said.

Flowers draws from several resources that include the RHWP partnership with Sholom Farms for prescription produce and a partnership between VCU Health and Feed More that helps provide food boxes.

“People can fill out a form online and then Feed More contacts them,” Flowers said. “We get them on a healthy path.”

VCU Health’s Food Is Medicine program also provides food boxes for patients and their families at Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU through a grant from the Rite Aid Foundation.

“The boxes contain heart-healthy, shelf-stable food. It’s enough food to make meals for three to four days,” said Kimberly Lewis, director of outreach and administration for VCU Health, who notes that she has seen an uptick in the number of people needing the boxes. “The overall positivity rate [for food insecurity] was 26% between June and December.”

Fighting food deserts with farmers

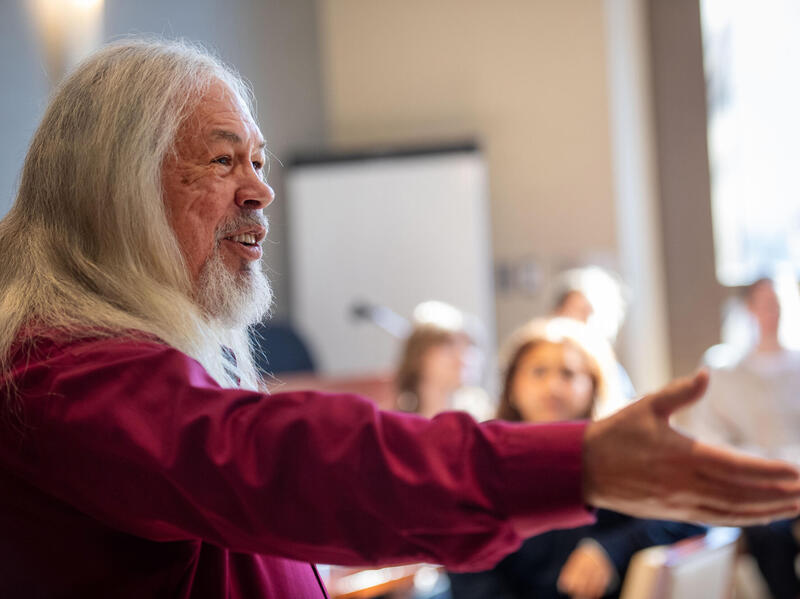

School of Business professor David Berdish and his students also strive to help fight food insecurity in the community through a project they have been working on in his classes Supply Chain Management and Analytics and Logistics and Distribution Strategy.

In the project, they work with small farmers in Charles City and the City of Richmond to aggregate their inventory. This inventory aggregation and distribution system will help farmers get their product to market and allow them to have a stronger business, which will enable them to give some of their product to food pantries.

“One of five people in Charles City doesn’t know where their next meal is coming from. I reached out to several farms in the area where we can aggregate the inventory and combine it in one location. The stuff they don’t use will go to food banks, etc.,” Berdish said.

Berdish is also working with the City of Richmond to identify small farmers. The project is currently moving from theory into practice.

“Our next step is to work with the City of Richmond to identify farmers who they think would want to work on this,” Berdish said. “In Charles City, we are working with food pantries and farmers.”

Students have identified locations for aggregate modules (refrigerated storage containers), said Berdish who is collaborating on this project with Stephen Fong, Ph.D, from the College of Engineering.

“We are trying to get the city to OK the locations and help facilitate,” he said. “We think by next year we could be up and running.”

Berdish, like environmental studies professor Jones and social work professor Kim, is part of the Sustainable Food Access iCubed core, which harnesses the combined expertise of researchers from diverse disciplines across VCU in an effort to address the complex issue of food deserts in urban environments.

Truly solving the problem of food insecurity or hunger will require intervention by the federal government to address systemic wealth inequity, Jones said. But he and his colleagues are looking at the ripple effect that even small improvements can make.

“Food insecurity is likely to negatively affect our graduation rates and other student success outcomes,” Jones said. “Our Ram community should focus around this issue, which is not only ethically sound, but should also improve VCU’s success metrics.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.