Jan. 16, 2024

Freedom of the press is more of a ‘roller coaster’ than a straight line, VCU professor says in new book

Share this story

In the United States, freedom of the press is such a core principle that the phrase itself, with roots in the Constitution, has special resonance. But if you think the concept is linear – that societies worldwide simply toggle from restricted to free press – it’s not that tidy.

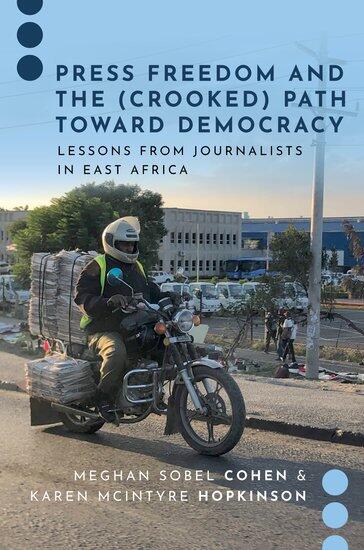

“That’s not it at all. Actually, it’s a roller coaster,” said Karen McIntyre Hopkinson, Ph.D., associate professor and director of graduate studies in Virginia Commonwealth University’s Richard T. Robertson School of Media and Culture. Her recent book “Press Freedom and the (Crooked) Path Toward Democracy: Lessons from Journalists in East Africa” explores the ride in three countries – Rwanda, Uganda and Kenya – where few researchers have examined press freedom.

McIntyre and co-author Meghan Sobel Cohen of Regis University in Denver interviewed and surveyed hundreds of East African journalists about their experiences and perspectives related to press freedom, and the authors lean heavily on African scholars as well.

McIntyre started researching journalists in Rwanda in 2016, and she and Sobel Cohen collaborated on numerous papers. McIntyre also earned a Fulbright scholarship in 2018 and lived in Rwanda for a year to intensify her research. Framed by its 1994 genocide amid civil war and a history of authoritarian rulers, Rwanda has a particularly fascinating media landscape, she said.

McIntyre spoke with VCU News about press freedom in her target countries – and how she connects it with the American experience and with her VCU students.

Why focus on press freedom?

When we started to do this research, we realized that press freedom was way more complicated than we knew. From a Western perspective, the indicators would suggest that there’s little press freedom or there’s not press freedom in Rwanda, according to the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index. But when we interviewed journalists there, a lot of them felt that they did have a lot of freedom. We started to dig into why this is. We learned that press freedom is a lot more complex and depends on how you view it. Also, press freedom is fluctuating. They’re gaining it and losing it, depending on a lot of variables, especially political variables. We realized that media development theories that exist have been helpful to us, but we also saw flaws in them. We thought it was important to highlight that.

What makes Rwanda’s media landscape so intriguing?

Journalists there feel that they are quite free. They would tell us, “Oh yeah, I’m free. I can write about whatever I want” – but then in the same breath, “I can’t write about any security issues, like military-related things” and “Oh no, I can’t write about the president.” They perceived their level of press freedom to be quite high, but they also acknowledge that they can’t write about certain things. So, I wanted to dig into why, and I learned there’s a lot of support for Paul Kagame, the president of Rwanda, within the country – likely because Rwandan citizens have to support the president. It’s illegal not to. But I also think that a lot of that support is genuine.

During focus groups with members of the public asking questions about their trust in media, it was interesting to hear people say they trusted the government-run media. I found that ironic, because the media contributed to the genocide. So-called journalists on the radio were spouting hate speech and encouraging people to kill their neighbors, revealing their hiding places. The media contributed and exacerbated the genocide.

We asked, how could Rwandans ever trust the media again after that? But they said they trusted especially the government-run media because Kagame – who, by a lot of standards, is authoritarian – was leading the charge to end the genocide. It’s complex. People call Kagame “the darling tyrant.” They’ve seen a lot of progress since the genocide. Rwanda has its problems, but it also is a major success story in terms of its recovery since.

How does press freedom in Uganda and Kenya vary from Rwanda’s experience?

Generally, Rwanda has the most restricted press. Uganda has more freedom. And then Kenya is the freest of the three. It’s interesting because there are degrees of freedom on different trajectories, like Rwanda’s press freedom is steadily going up since the genocide. But Uganda’s press freedom, which is higher, is going down now. And then in Kenya, journalists acknowledged it was more consistent. They’re the freest, and the journalists believed that they felt the freest. We liked this way of looking at it in that there are the three levels: least free, medium and most free. It gave us an interesting framework in the book.

Tell us a bit about your research and findings.

Our methods are based off in-depth interviews and a survey of journalists in the three countries – we interacted with over 500 journalists.

Other scholars have looked at press freedom as a linear process, going from not free to free. We argue that’s not it at all. It’s a roller coaster. And there are variables that impact press freedom. We considered how recently a country had a major conflict, like genocide or some other significant civil war. The closer a country is to having a major conflict, the more restricted their presses.

Political variables played a huge role, like who the president is and how they feel about press freedom. In a country like Rwanda, they’ve had the same president for decades. Kenya has much more change in their presidency, and so Kenya has much more press freedom.

Other categories we analyzed included factors like international linkages. Kenya has many more international links than Uganda and Rwanda. And we think that allows them to have more press freedom. A final factor was how a country’s civil society is. In Kenya, the citizens are much louder and more empowered. And in Rwanda, people are very quiet. In Kenya, citizens will speak out. That also helps press freedom.

How does the book project inform your VCU work and possible future research?

The fieldwork we did for the book better positioned me to recruit and work with international students. And in my classes, because I am aware of media systems in countries with less press freedom than the U.S., I am able to talk about the U.S. media landscape in context, widening students’ worldview.

I also have combined my two threads of research by studying constructive/solutions journalism in the same countries where I study press freedom. There is also a connection, or lack thereof, in that in countries with low levels of press freedom, a concept like constructive journalism – which involves applying positive psychology techniques to the news process in an effort to create more productive and solution-focused stories – might be hijacked and used to spread government propaganda. I am interested in doing more research on constructive/solutions journalism in non- or emerging democracies.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.