Nov. 3, 2025

Prison writing tells an American story of mass incarceration

Share this story

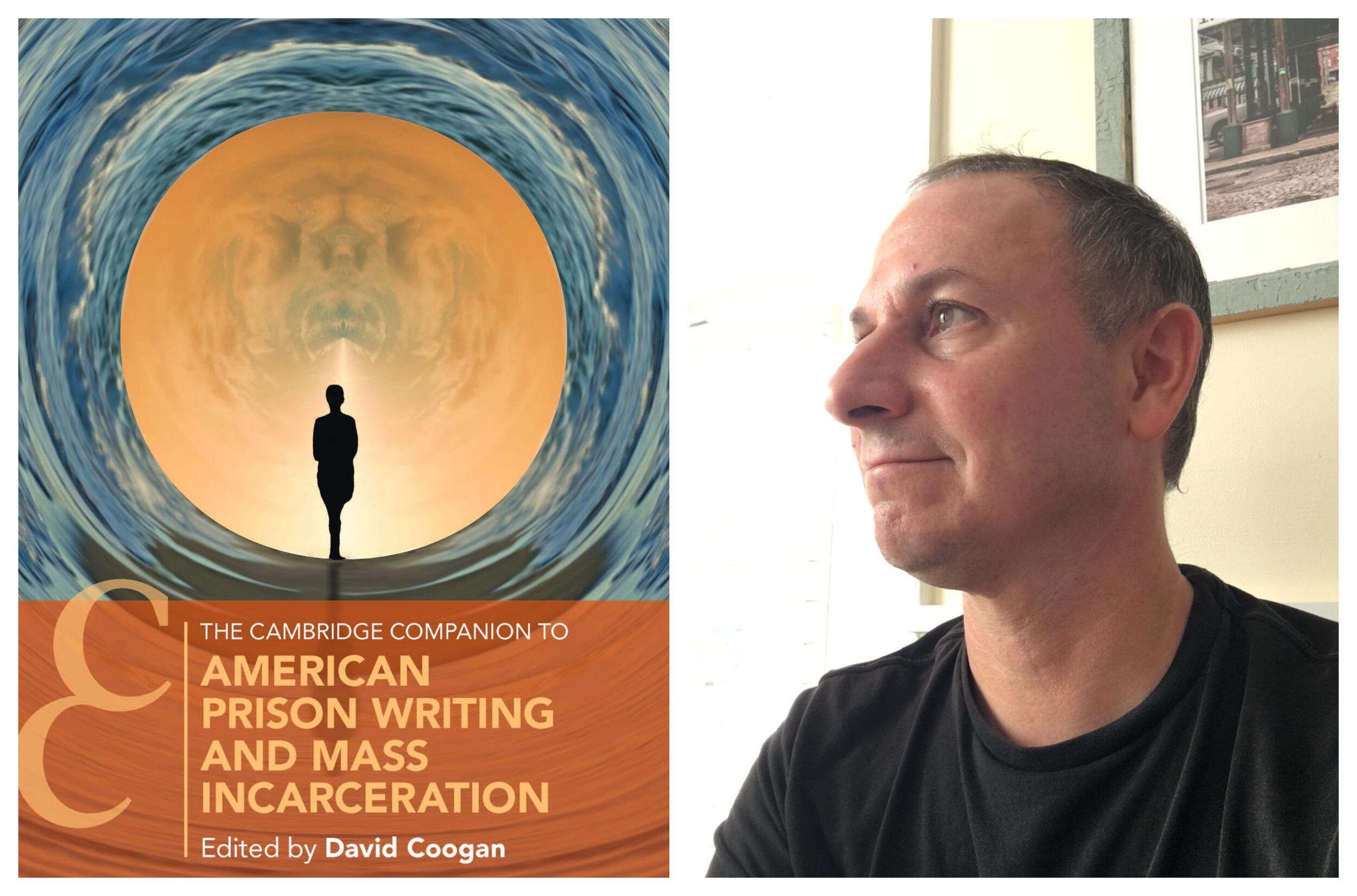

Inspired again by his time as a writing teacher in the Richmond City Jail, David Coogan is adding another chapter to his work giving voice to the incarcerated.

Coogan, Ph.D., an associate professor of English in the Virginia Commonwealth University’s College of Humanities and Sciences, is using his new book – “The Cambridge Companion to American Prison Writing and Mass Incarceration” – to trace history through the eyes of those who lived it.

His work curating and editing the collection, which was published in October, began years ago when teaching a memoir writing class at the Richmond jail, an experience that also inspired his 2015 book, “Writing Our Way Out: Memoirs from Jail.”

At the time, “I knew so little about jails and prisons or the people who got caught up in them,” Coogan said. “I began reading the published memoirs of people who had survived, and that gave me the bigger picture I needed.”

From the onset of mass incarceration in the early 1970s to the 21st century, the collection brings together accounts from figures including political activist Assata Shakur, journalist Wilbert Rideau, and author and death row inmate Jarvis Jay Masters, who has long maintained his innocence.

VCU News asked Coogan for quick insight about the importance of prison writing.

How has prison writing evolved alongside mass incarceration?

In the 1970s, mass incarceration began as a governmental crackdown on activists seeking social change in American society. It was less about stopping crime than stifling dissent, particularly from Black revolutionaries who did not just want to abolish prisons but also the societal forces that sustained them.

By the end of the 20th century, the prison population had gone from 300,000 to over 2 million, while mass incarceration had become a terrible “solution” to the social problems that we were unable – or unwilling – to face in society: poverty, racism, drug addiction, sexual assault and other forms of trauma that can lead to crime but which are often undertreated by a lack of affordable health care.

When revolutionary movements retrenched in the 1980s through the War on Drugs and then the 1994 federal crime bill (“Three Strikes, You’re Out”), American prison writers began witnessing and seeking self-determination from these increasingly cavernous warehouses. For writers trying to heal from traumatic life experiences and from the trauma of prison itself, memoir became the preferred genre.

What do you hope readers will take away from your new collection?

Mass incarceration works by characterizing the people in prison as a “mass” of anonymous, abhorrent criminals. But for 50 years, people in prison have been writing to expose the lies, shore up their own humanity, build community and imagine a better society that is more humane, one with less derailing and less pain. This book gathers them together into a chorus of resistance, witnessing and healing. It’s a beautiful sound.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.