Dec. 17, 2025

VCU sturgeon expert collaborates with Upper Mattaponi Tribe to expand tracking

Carrie Fox hauled a green net over the side of a small skiff on a cloudy, brisk day in December. Though teeming with invasive blue catfish, the net also held one of the James River’s most iconic species: the Atlantic sturgeon.

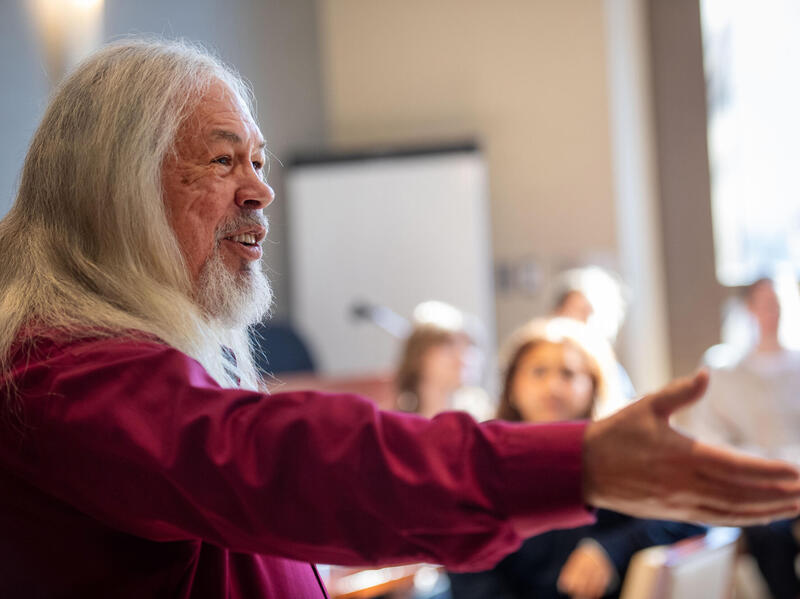

“We got one!” said Matt Balazik, Ph.D., as he fished through the net to pick out the juvenile sturgeon. Less than 2 feet long, the spiny fish – one of three caught that day – writhed in his hands as he transferred it to a plastic water barrel.

The Virginia Commonwealth University expert estimated that this sturgeon, which could live for over 50 years, was nearly 2 1/2 years old. And while Balazik is a seasoned hand, the thrill of the catch is still relatively new to Fox, a fisheries technician for the Upper Mattaponi Tribe and a member of the Pamunkey Indian Tribe.

Balazik has spent almost two decades chasing sturgeon up and down the James. Now he, Fox and other members of the Upper Mattaponi’s fisheries program are working to bring his sturgeon smarts to a new frontier: the Mattaponi River, which runs through the tribe’s home territory in King William County, about 30 miles northeast of Richmond.

“We’ve been sampling the James for close to 20 years now, and we have a better guess of where they’re going to be,” said Balazik, a research faculty member at VCU’s Rice Rivers Center, part of the College of Humanities and Sciences. “But this hasn’t been done in the Mattaponi.”

In November 2024, Balazik started working with the tribe and Fox, who graduated from VCU in 2023 with an undergraduate degree in gender, sexuality and women’s studies, to apply his sturgeon sampling and research techniques to the Mattaponi River. The researchers, whose work is funded by a three-year National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration grant, are most eager to catch juvenile sturgeon, whose populations are relatively unstudied in both rivers.

“We’re trying to figure out the nuances, because every river is different,” Balazik said. “You try to paint these things in a uniform manner, like all the populations are functioning the same. They’re not – anyone will tell you that.”

By teaching and working with members of the tribe, Balazik hopes his sturgeon work can take on a new life on the Mattaponi.

“Who better to do that work, to monitor the sturgeon, than the Upper Mattaponi Tribe?” he said.

Tracking a unique creature

The Atlantic sturgeon’s life history is as unique as the prehistoric fish itself. Crested by spiny scutes, adult sturgeon can grow up to 14 feet long, and they spend most of their time in the ocean. But they swim up their home rivers along the eastern coast of North America to spawn in either the fall or the spring once mature, when they are between 10 and 30 years old depending on water temperatures.

The sturgeon, which was overharvested by the caviar trade in the late 1800s and overfished throughout the 20th century, finally gained coastwide protection in 1998, and it was listed under the federal Endangered Species Act in 2012. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that scientists, including Balazik, began to track sturgeon populations on the James River. To date, Balazik has caught over 900 adult sturgeon and over 1,000 juveniles, with more than 90% of them caught during a 2018 boom year.

But catching the fish is just the beginning. Before releasing the juvenile sturgeon, Balazik and Fox inject electronic tags under the skin of each fish and fit them with yellow, external tags that will tell other researchers that the fish has already been captured. They also measure each fish and clip off a small piece of fin for DNA analysis.

Then, they release the fish back into the James. Each juvenile sturgeon helps the researchers find out how many of the young fish are surviving in the river’s turbid waters. So far, there aren’t quite as many as Balazik would hope, despite a robust population of adult sturgeon born about 30 years ago.

“We’re not finding the teenagers. We’re not finding young adults, which means that we’ve had problems for some time of younger fish surviving to fill in those young adults,” Balazik said.

That could be due to any number of environmental conditions, or due to predation by the omnipresent blue catfish. But before Balazik and Fox can figure out what’s causing the problem in the James, they need to know how big it really is – and the only way to do that is to catch and tag juvenile sturgeon.

“Ideally, if you know where they’re at, what time of year they’re here, what might be harming them, you can mitigate that and try to change things to give them better recruitment numbers and survival rates,” Fox said.

“Who better to do that work, to monitor the sturgeon, than the Upper Mattaponi Tribe?”

Matt Balazik, Ph.D.

A fish worth the wait

Sampling trips like this one on the James River fulfill a research purpose, but they also give Balazik time to train Fox and other members of the Upper Mattaponi’s fisheries program. And after almost a year of sampling, Fox was eager to finally catch a sturgeon on the Mattaponi.

“This is what I want to do. I just have to be patient. And, I mean, I enjoy it regardless,” she said, as the skiff cruised down the James. “So, I’ll wait. I’ll wait forever for them.”

But as it turns out, Fox didn’t have to wait forever. One week later, she and Balazik caught their first tiny, juvenile sturgeon on the Mattaponi after a long day of trawling, and “emotions went haywire,” Balazik said.

Fox is lucky – it took Balazik 11 years to catch a juvenile sturgeon on the James. Once the team starts to consistently catch the fish on the Mattaponi River, the tribe employees will use the same techniques to independently track sturgeon in their waterways.

“This is the first of many sturgeon the Upper Mattaponi Tribe fish research team is going to interact with on the Mattaponi,” Balazik said. “However, this one we will never forget.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.