Nov. 28, 2018

How forests are a key piece in the climate change puzzle

Share this story

The U.S. Global Change Research Program on Friday released a major report that provides a current scientific assessment of the carbon cycle in North America and its connection to climate and society.

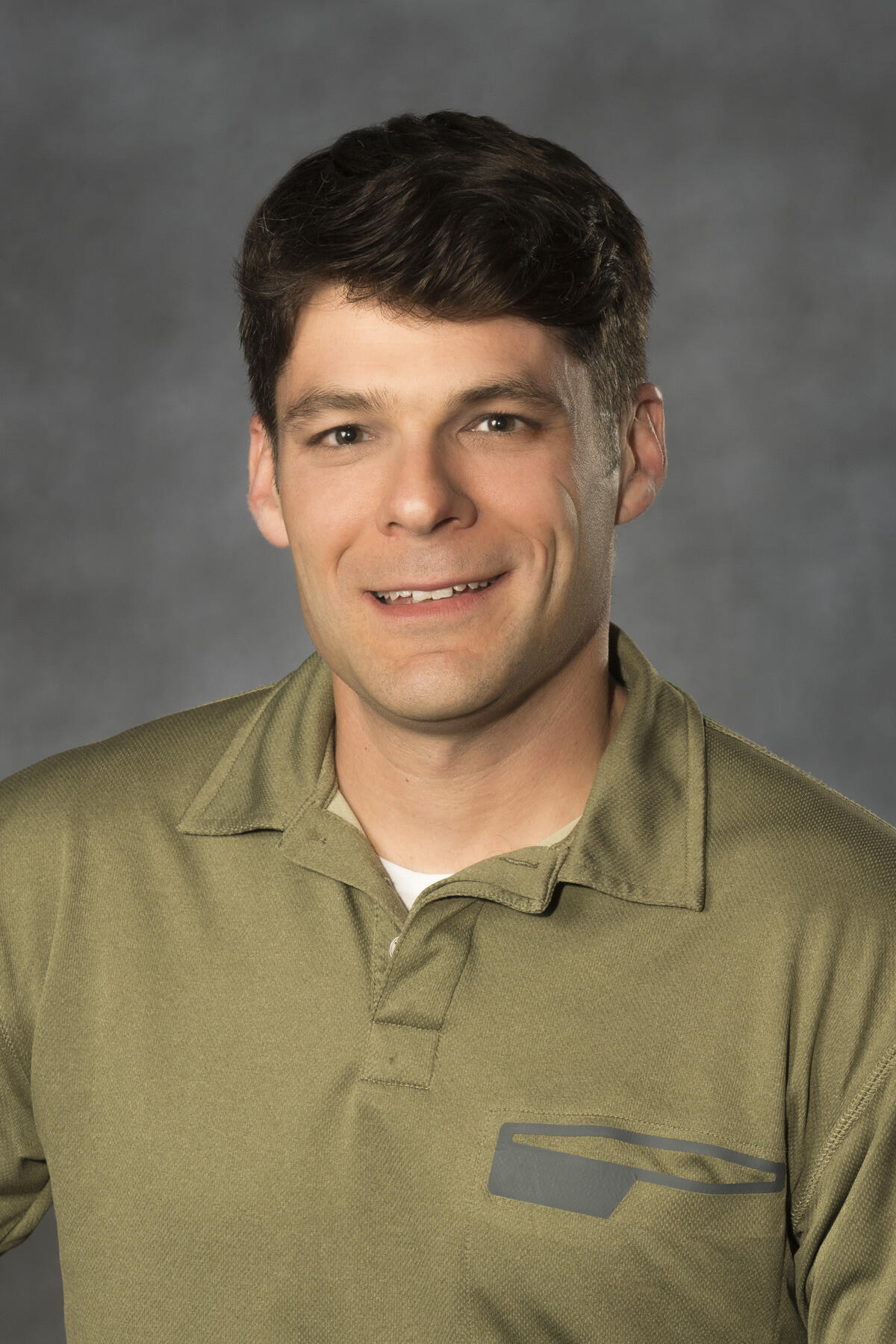

Chris Gough, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Biology in the Virginia Commonwealth University College of Humanities and Sciences, was a contributing author to the report’s chapter that focuses on forests, and the role they play in the carbon cycle and climate change mitigation.

The report, the Second State of the Carbon Cycle Report, or SOCCR2, was developed by more than 200 scientists from the United States, Canada and Mexico. It was released alongside the National Climate Assessment, which focuses on the state of the climate, the scientific understanding of the climate system, and the impacts on human health and economics. The SOCCR2 report, meanwhile, provides the latest science and data on the underlying causes of those changes, including impacts from urban areas, energy systems and ecosystems.

“The State of the Carbon Cycle is intended to be an accessible and approachable synthesis of the science for the public, managers and policymakers to consult as they consider solutions,” Gough said. “So, for example, in my area that might be better management of a forest for the purpose of sequestering carbon.”

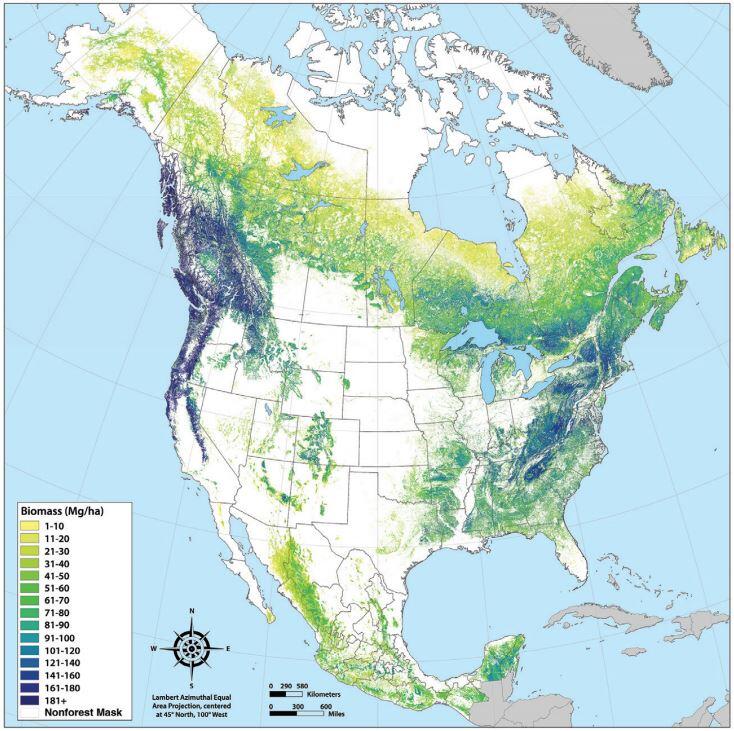

There are an estimated 723 million hectares of forestland in North America, according to the report. These forests, particularly those in the United States, sequester a great deal of carbon. In doing so, they are providing an ecosystem service by at least partially offsetting carbon dioxide emissions to the atmosphere. The carbon removed from the atmosphere through photosynthesis accumulates in biomass and soils.

“The report provides quantitative assessments of how much North American forests offset our carbon emissions,” Gough said. “A key finding is that forests are a relatively effective and inexpensive way to partially offset our carbon dioxide emissions to the atmosphere. And proper management in fact can improve the capacity of forests to sequester carbon.”

At the same time, he said, the report shows that mismanagement or poor management, and land-use conversions away from forests — such as to agriculture — will diminish the capacity of forests to scrub carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

The report also explores how disturbances — such as hurricanes, fires raging in Western states and insect pests — are increasing in frequency and extent, thereby also reducing the capacity of forests in North America to sequester carbon.

Gough said he hopes the report sends a message to policymakers that forest management, preservation and sustainability are important to the reduction of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

“I hope that [policymakers] will appreciate that forests play a prominent role in shaping climate by offsetting carbon dioxide emissions,” he said. “An additional goal of the report is that they will have a better understanding of what activities will both promote and reduce carbon sequestration in our forests.”

Gough’s lab at VCU focuses on how climate, disturbance and forest age affect carbon sequestration. Recently, work supported by the National Science Foundation has focused specifically on disturbance interactions with forest carbon cycling, asking whether disturbance changes the trajectory of carbon sequestration, if at all.

“In some cases we’re finding, for example, that forests can be quite resilient to disturbance and in other cases not so much,” Gough said. “So we’re trying to understand: Why are some forests resilient and rebound quickly following disturbance and others are more vulnerable?”

His lab is also interested in the effects of climate change on forest carbon sequestration. His group, in partnership with The Ohio State University and the University of Michigan, operates a U.S. Department of Energy supported AmeriFlux “core site.” These sites are long-running carbon sequestration monitoring stations supplying data freely to the research community and policymakers.

“We are associated with one of the longest running carbon sequestration tower sites in the country,” Gough said. “So we have access then to this long-term pairing of carbon sequestration and climate data. We’re able to look at and observe real-time changes over 20 years in climate and how that’s affecting forest carbon sequestration at our site.”

The lab also looks at what processes affect carbon sequestration as forests get older.

“We’re really interested in the ecological and carbon sequestration value of old-growth forests,” he said. “Ecological theory suggests aging forests decline in their capacity to sequester carbon. But we’re not finding that. And we’re trying to understand why.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.