May 23, 2019

Who was Mr. Baptiste?

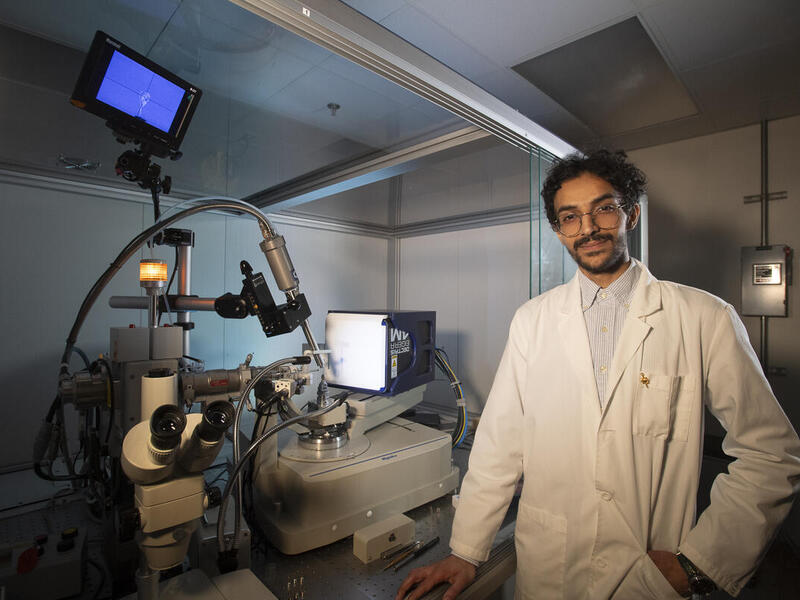

A VCU professor’s investigation may have just proven the identity of one of the first Black American composers.

Share this story

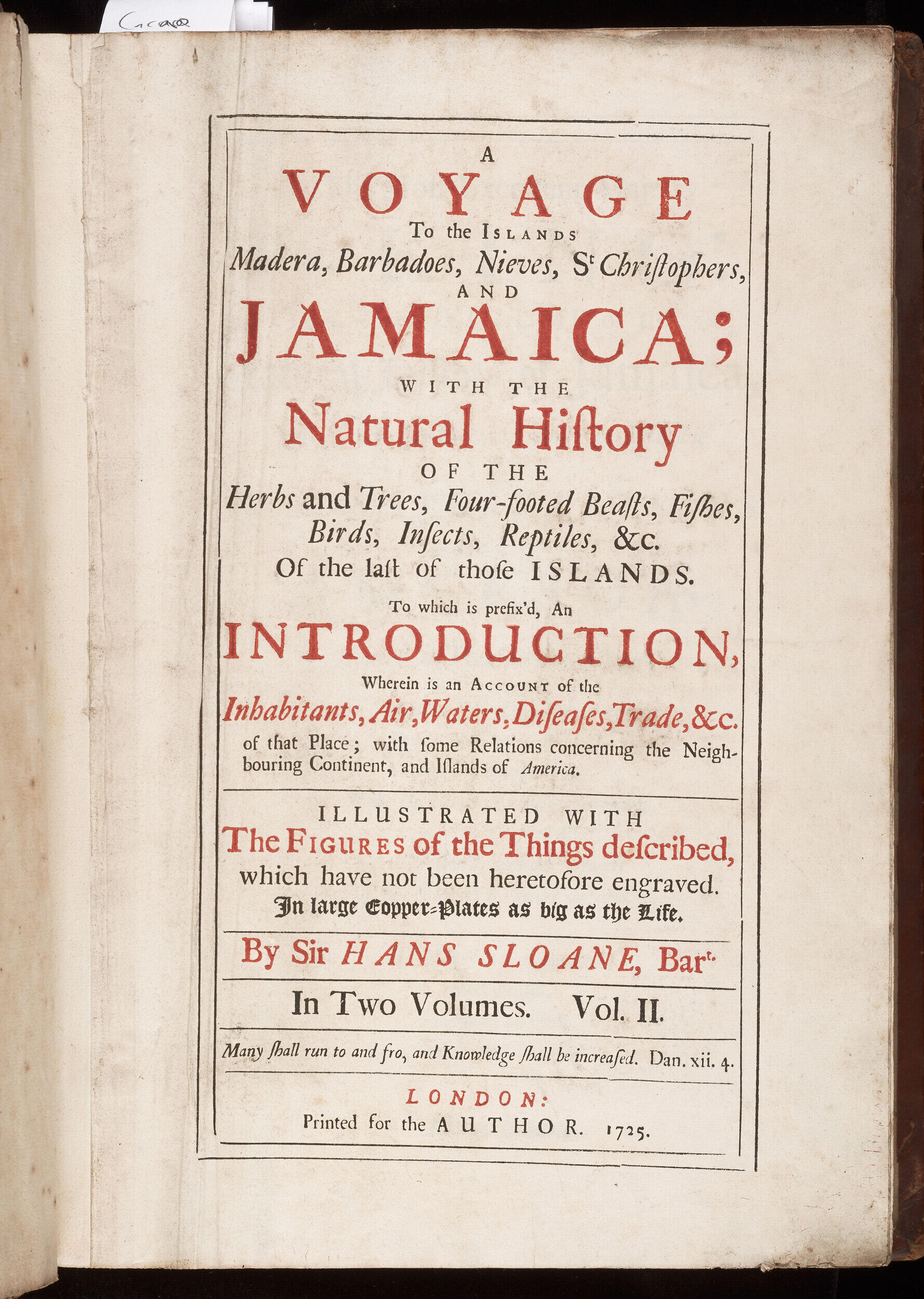

In his 1707 account of colonial life in Jamaica and other Caribbean islands, British naturalist and physician Hans Sloane describes happening upon a festival in 1688 where a “great many Negro musicians were gathered together.”

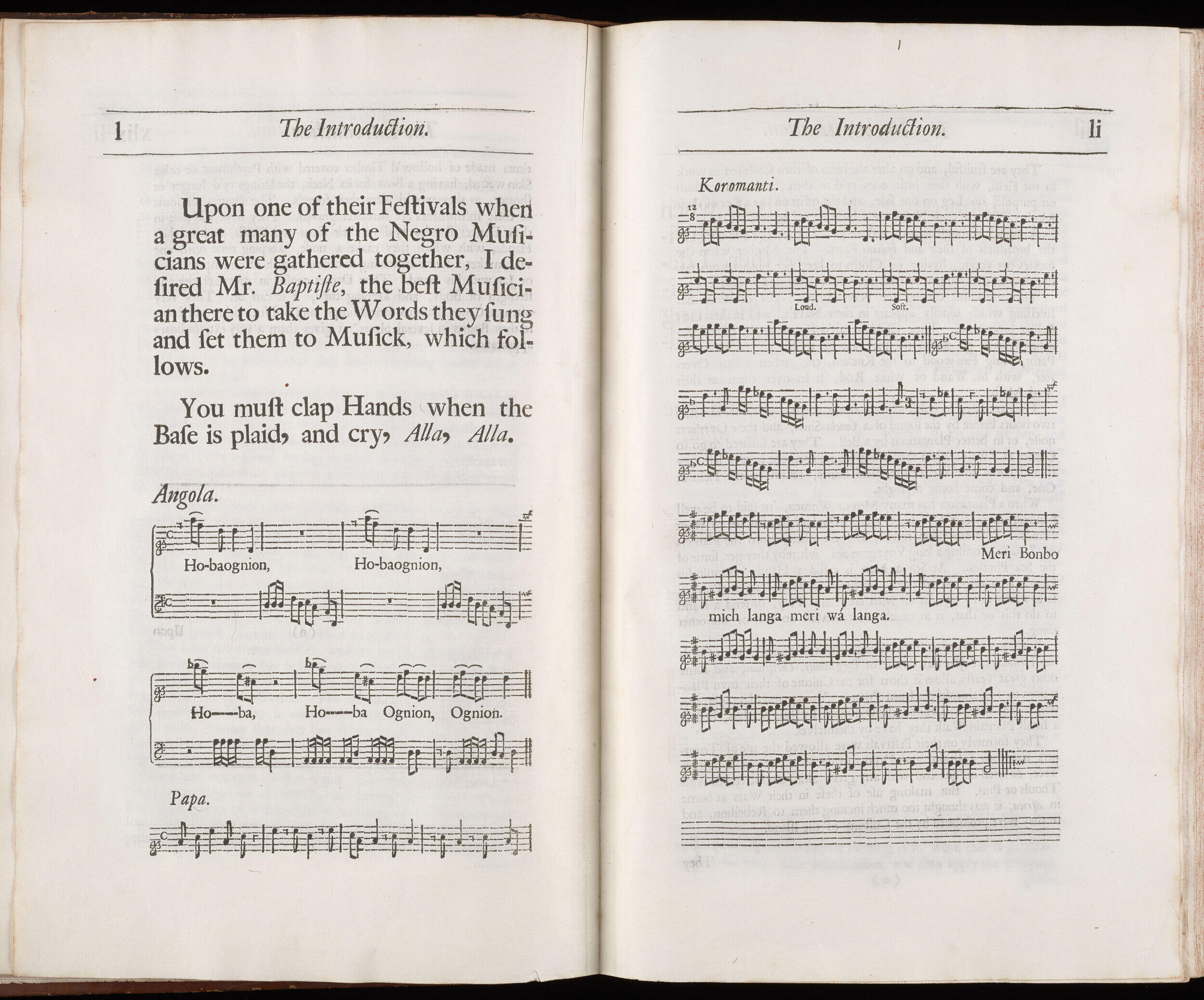

“… I desired Mr. Baptiste, the best musician there to take the words they sung and set them to music,” wrote Sloane in “A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica.”

Baptiste’s sheet music, transcribed over two pages in Sloane’s book, is the earliest known example of published African diasporic music in the Caribbean. Previous research assumed Baptiste was a white colonist from France.

Virginia Commonwealth University professor Mary Caton Lingold, Ph.D., an expert on colonial travel writing — such as “A Voyage to the Islands” — has long suspected that “Mr. Baptiste” was, in fact, a black musician and composer.

“I decided, you know what? I’m going to try to prove this,” said Lingold, a professor in the Department of English in the College of Humanities and Sciences. “I’m going to try to find Mr. Baptiste.”

Now, after an investigation that has taken her to national archives in Jamaica and the British Library in London, Lingold believes she is closer to proving the hypothesis.

And, if true, that would make Baptiste one of the first, if not the first, published black composers in history.

“There were many free people of African descent, especially in the French colonies at the time, many of whom were musicians,” Lingold said. “Why would a French colonist — a white guy from Europe — be the best musician in Jamaica? Why is he not a person of color? Why do we assume that he was a white colonist?”

Searching for clues

Last summer, Lingold found four records in Jamaica’s national archives from 1655 to 1730 that mention a Mr. Baptiste. One was a naturalization record that shows Baptiste was of African descent. The others are a marriage record, land document and an estate inventory related to a Baptiste.

“There are actually a lot of records in the national archives [during this time period],” Lingold said. “If you were a planter, your name is going to be in those records over and over and over again. They’re fairly comprehensive in some respect. In all of those records, I only found four documents that have to do with anybody with the name Baptiste, which suggests that one of them, or if they’re all the same person, is my guy.”

Beyond the records showing there was a Baptiste of African descent in Jamaica during the correct time period, the theory that the “best musician there” was a person of color makes sense for several reasons, Lingold said.

The music itself holds clues. The sheet music in “A Voyage to the Islands” is for three compositions — titled “Angola,” “Papa” and “Koromanti” — that reflect three distinct African musical traditions.

Whoever authored the sheet music would have at the very least been literate in African musical forms.

“Who would be more likely to be literate in African musical forms than an Africa descended musician who had grown up in the colonies?” she said. “It just makes more sense.

“Now are these the most faithful representations of all time? Absolutely not. But they are extraordinarily distinctive and I believe someone who hailed from the Caribbean, and particularly someone with personal connections to enslaved communities, would have been more equipped to be able to execute the significant distinctions.”

‘A Voyage to the Islands’

The question of Baptiste’s identity has been a question long tied to Lingold’s research in colonial travel writing. Before joining VCU in 2017, as a doctoral candidate at Duke University, she collaborated with her mentor, Laurent Dubois, Ph.D., a professor of history at Duke, and composer and instrumentalist David K. Garner on a project called “Musical Passage: A Voyage to 1688 Jamaica.”

The online project tells the story of the sheet music in “A Voyage to the Islands” with the goal of shedding light on the early history of African diasporic music, which is among history’s greatest and enduring cultural legacies.

As part of “Musical Passage,” the collaborators set out to interpret the music transcribed by Mr. Baptiste. It was through these collaborations that Lingold and her colleagues began to think differently about Baptiste’s identity. The website provides two versions of “Angola,” one with vocals by Lingold, a musician in her own right, and fretless banjo by Garner; and the other adapted for chorus, fretless banjo and percussion.

“Angola was the name used for the coastal region of Central Africa, and also sometimes for enslaved people from that area,” the site says. “The song ‘Angola’ stages a lively conversation between the upper and lower registers in a call-and-response pattern. There are many clues in the notation and in this case, we believe that the high pitches in the vocal melody may refer to a style of singing with a reaching quality that is challenging to represent in the notation. The piece has a decisive ending, unlike the other tunes. The rhythmic pattern in the bass line may have been performed on a stringed instrument like a banjo, or on another instrument like a balafon, which is a type of xylophone common in parts of West Africa and among the African diaspora.”

“Musical Passage” also speculates on the identity of Baptiste.

“The only thing Sloane tells us about Mr. Baptiste, who authored the musical notation, is that he was the ‘best musician there,’” the site says. “Although some have assumed that he was a European colonial elite like Sloane, we conjecture that he was actually one of the ’Negro musicians’ performing that day.

“Where did Mr. Baptiste learn how to read and write music in the European tradition? His name suggests that he was probably not from Jamaica, but instead was a free person of African descent from a nearby colony. The last name ‘Baptiste’ was common among free people of color in French-speaking Saint-Domingue, Martinique, and Louisiana.”

Lingold and her collaborators theorized that if Baptiste came from one of the Catholic colonies like France or Spain, he may have had an opportunity to learn European notation in a church setting, where enslaved or free young men were often trained in liturgical music. The French colony Saint-Domingue (colonial Haiti), was home to a rich and theatrical life in which many free people of African descent came to perform in the theater as musicians. Such a background might explain how Baptiste was able to interpret and transcribe the music Sloane described.

“[Baptiste] was clearly a skilled listener and musician: each of the pieces [in “A Voyage to the Islands”] is in a very different style, and showcases careful attention to the intricacies of melody and rhythm,” they wrote. “We may even most usefully think of Mr. Baptiste as a composer, someone who was a frequent participant in such gatherings and therefore responded to Sloane’s request — ‘to take the words they sung and set them to music’ — by creating pieces inspired by and channeling what was performed at this and other ‘festivals.’”

One of the first Black American composers?

The assumption that Baptiste was a white colonist instead of a musician of African descent reflects historical biases, Lingold said.

“I’m trying to prove essentially that this Mr. Baptiste may be one of the first — if not the first — published black composer in the world,” she said. “But this is the thing, of course: Black people always have to jump through hoops to prove that they are who they say they are, that they know what they know. And that’s because of the racism that was born out of this period, and born out of slavery.”

Interestingly, on the other hand, Baptiste likely would have considered himself neither black nor a composer, said Lingold, who will be presenting a paper on this topic in the summer at conferences in Portugal and Boston.

“Both of these categories are historically specific categories that may have not resonated for him,” she said. “Even today, race is construed differently in Jamaica than in the U.S, where we have the ‘one-drop rule’ notion of you’re either black or you’re white. In Jamaica, when I told people there that I think [Mr. Baptiste] may be one of the first black composers, they seemed more interested in the fact that he was a Jamaican composer, rather than a black composer.”

That Sloane gave Baptiste the “Mr.” honorific, she said, suggests that he would have been perceived differently than an enslaved person from Africa at the time.

“For some Europeans, class would have trumped race in this time period,” she said. “That changed dramatically over the course of the 18th century, but Mr. Baptiste would have been seen as a free person with personal property and a profession. But musicians weren’t particularly important. Professionals usually were from a lower-class background, which is one of the reasons it became an attractive career for free people of color who were eager to climb the economic ladder and obtain more social and geographic mobility. So yes, I want to prove that he’s one of the first black composers. But on the other hand, that’s kind of an anachronistic notion.”

With historical investigations of this sort, Lingold said, we may never be able to say with 100 percent certainty that Baptiste was a musician of African descent.

Yet, she said, “I can argue with every confidence that the evidence suggests that this man was likely the first black composer, and that’s something to celebrate, and a legacy to remember.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.