June 5, 2020

Remarks by Aashir Nasim, Ph.D.

Share this story

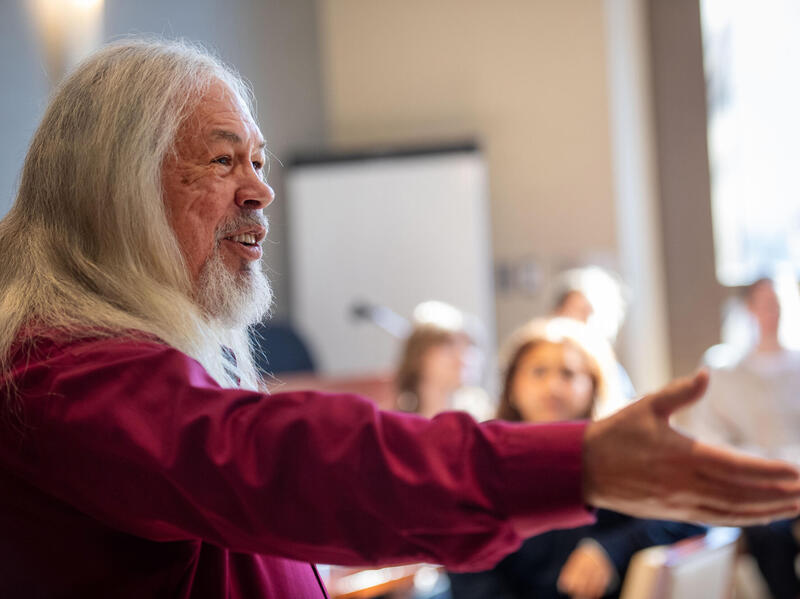

Aashir Nasim, Ph.D., vice president of VCU's Office of Institutional Equity, Effectiveness and Success, addressed the Board of Visitors on Friday:

As an urban public research university, formed during the height of the civil rights movement in 1968, we understand rather intuitively how the pandemic and the most recent protests have impacted people’s lives, and their livelihoods.

While we haven’t experienced anything like this pandemic in our lifetime, at VCU, we’ve certainly realized that most public health crises disproportionately impact racial and ethnic minority populations with respect [to] cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, cancers and the like. COVID-19 being no exception.

There also is a continuing public health crisis with respect to housing and food insecurity. As more and more people lose their jobs, we know African American and Latinx adults experience unemployment rates double and sometimes triple the national average. The lack of meaningful work adversely impacts the agency and generativity of mothers and fathers who can no longer afford to provide for their children, much less afford the cost of attendance at a four-year university. It also changes the equation from integrity to despair for older adult populations who now find themselves subjected to employment discrimination and stereotypes about their vulnerabilities.

And we must acknowledge that there long has been a public health crisis with respect to African Americans and their interactions with law enforcement. Within many African American families, dinner-time lesson plans for children have undergone what I will call a curriculum transformation. The lessons the past few months are not only related to teaching their children about washing their hands and social distancing to prevent infection from viruses such as COVID-19, many African American parents have reformulated the curriculum to teach their children about the new viral strains of racism — yes, teaching them to not just wash their hands, but to also show their hands, and to not just socially distance themselves from strangers, but to also physically distance themselves from those who were sworn to serve and protect them. Indeed, there is a public health crisis.

Many of our faculty and staff understand how this pandemic has fundamentally altered the life of our students, students who have had their dreams deferred, students who have had to return to a home that is no longer theirs. For some of our LGBTQ students, to return home only to go back inside of a closet, for some of our students who feel the guilt and shame of missing a class on zoom because of “family issues.” We know their stories, and if you hear enough of these stories, then you see a grander narrative taking shape.

The narrative is that access alone isn’t enough. Opportunity alone isn’t enough. Rather, engagement is where we need to be. Meeting our students, our employees, our patients where they are. And to meet them where they are, we must recognize and respect their humanity and their right to belong.

We don’t call ourselves a safety net hospital because it sounds glamorous. We are a safety net hospital because we believe in the integrity and value of every human life.

We don’t tout the number of students who are first generation, limited wealth or racial or ethnic minority because we are seeking some praise or reward. In fact, in past credit agency reports, it stated that our student demographic was a mitigating risk to our university’s credit rating. We don’t serve these student populations for some economic gain as some have suggested. We serve these student populations because we believe in the power of education to transform their lives, their families and their communities.

And, we certainly don’t worry if people outside of VCU don’t think we are considering all sides of an issue when we send statements of solidarity and support that are centered on our core values as a university. We will not get looped into parsing the false dichotomies between party crowds on our beaches during stay-at-home orders and protesters in the streets of our major cities after curfew.

As a university, when we state the phrase “black lives matter,” it does not mean that other lives matter less. It means that in consideration of the socially-constructed hierarchies of race that we all are a part of, knowingly or unknowingly, that if I can get you to agree that a black life matters, then by a universal human ethic every life matters too. In other words, if I can convince you that Aashir’s life has value, then I know you can value everyone else’s life.

So, when our president writes “black lives must matter if we ever are to realize the potential of VCU’s shared community and the vast privileges of belonging to a global community,” this is what he means: There is a universal human ethic to valuing all lives irrespective of the color of their skin or their lot in life.

Listen, you don’t need me to tell you what is happening. Unless you’ve been lost somewhere in a Netflix series the past few months, you know what we’re facing as a nation.

So, let me share with you how this is how this will play out across higher education for the next few months.

I am sharing this because I don’t want you to worry when you see that VCU is not doing the same things as your alma mater or your son’s or daughter’s university.

This is how most universities will approach the fall semester with respect to PPE: pandemic, protests and elections.

There will continue to be debate and deliberation about university statements.

Presidents will charge committees, task forces and workgroups to examine “the issue” and how they can best meet the needs of their students.

There likely will be exceptions to the hiring freeze due to the pandemic. Universities that hadn’t had a chief diversity officer probably will splurge to hire one now.

A year or so will pass and the task force under the direction of the newly appointed person to oversee this process will release a report with recommendations.

Most recommendations will come with a price tag, and universities still attempting to recover from a wave of COVID-20 will try to integrate these recommendations within new university priorities.

I know this sequence of events all too well because I have seen it play out this way across institutions of higher learning crisis after crisis. And this simply doesn’t pass with our students, not VCU students. They too know the game.

Therefore, we will not spend time doing every single suggestion you will read during the next few months in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Inside Higher Education, the Hechinger Report.

In fact, what other universities will do in large part is inherently designed to mute or resist systemic change.

But our president is beyond simple rhetoric. He’s stated in no uncertain terms that it is long past time for change. Importantly, he didn’t wait to say this when the pandemic fell upon us, he didn’t wait to say this after Ahmaud, Breonna, and George were killed. He said this to me when I assumed this position in 2018.

Therefore, in December 2018, we announced a task force on Individual, Institutional and Systemic Bias. This task force of more than 80 faculty, staff and students concluded its work in October 31, 2019 and provided recommendations to 24 problem situations that impacted our university with respect to bias and discrimination.

Since then we have been working on implementing the following:

With respect to our physical environment: We’ve understood for quite some time what the symbols of oppression mean for racialized minorities. Therefore, the VCU History and Civil Rights committee co-chaired by John Kneebone and Jodi Koste conducted a study across 2018-19 on Confederate commemoration on campus. Following this study, a VCU policy was approved by you and the VCU Committee on Commemoration and Memorials was charged. The committee has met several times and will met again in the coming weeks, with a plan presented to you by the first meeting in fall to dismantle the remaining vestiges of an unwanted history on our campus. Upon your good vote of yea, we will begin dismantling.

In terms of policy development: In the next few weeks, we will have completed our revision of the university’s non-discrimination policy. We realize the legal thresholds for discrimination are tough to reach; at the same time, we realize the deleterious effects of death by a thousand microaggressions. We soon will have an alternate pathway to adjudicate these matters in a way that is affirming for those who have been aggrieved.

With respect to non-discrimination training for employees: We understand the value of non-discrimination training. This fall, we will have completed a training module for employees. However, while mandatory non-discrimination courses increase accountability and compliance, evidence shows they do not change attitudes and cognitions. As such we have developed a compendium of diversity and inclusion courses and seminars and programs for faculty and staff, but also courses — free of charge — for students such as hashtag activism and promoting social justice. We began offering these courses and seminars several months ago.

With respect to faculty hiring: We have developed an affirmative action planning executive dashboard to account and monitor our progress toward hiring minorities and women; those with disabilities; and protected veterans.

And, this fall, we will implement a required diversity statement for all faculty positions so that any future hires must explicitly demonstrate how their teaching, research and service advances diversity and inclusion.

With respect to gender identity diversity: In the coming weeks, we will launch our “Call me by my name” campaign. One of the ways that we make inclusion real is by recognizing that individuals have the right to use names other than their legal name, to identify with the gender they know themselves to be and to utilize the pronouns that best fit them. This is what it means to meet people where they are, you call them by the name they wished to be called by.

But, make no mistake about it, even in doing these things, we don’t always get it right. And our students let us know this in no uncertain terms. Therefore:

With respect to incident reporting, feedback and responsiveness: We recognized some time ago that we’ve had an issue with providing mechanisms for our employees and students to report incidents of bias and discrimination. We will be overhauling our portals for employees and students to report adverse events. We also will implement a feedback loop to allow for constant feedback from employees and students on what’s working for them and what isn’t.

Also, we can no longer simply skirt around our curriculum. In 2019, the president charged a curriculum transformation task force to evaluate ways in which we can create a more dynamic and engaging curriculum for our students. We’ve offered recommendations, and over the course of the next several months, we will continue to work with faculty to implement inclusive teaching pedagogies that are student-centered and meet our students where they are in terms of their learning trajectories.

Finally, with respect to the health and wellbeing of our most vulnerable populations: The institute that I direct called the Institute for Inclusion, Inquiry and Innovation has teamed with the Office of the Vice President for Research and Innovation to double the award amount for every COVID-19 rapid response grant that focuses on achieving health equity in older adult, racial minority and other vulnerable populations.

In these ways, from a VCU culture and climate perspective, we are absolutely committed to our students, employees and our patients as we enter into the 2020-21 academic year here at VCU.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.