Dec. 10, 2025

Study reveals genetic overlap of 14 psychiatric disorders, explaining why patients often have multiple diagnoses

Share this story

An international collective of researchers is delivering new insights into why having multiple psychiatric disorders is the norm rather than the exception. In a study published today in the journal Nature, the team provides the largest and most detailed analysis to date on the genetic roots shared among 14 conditions.

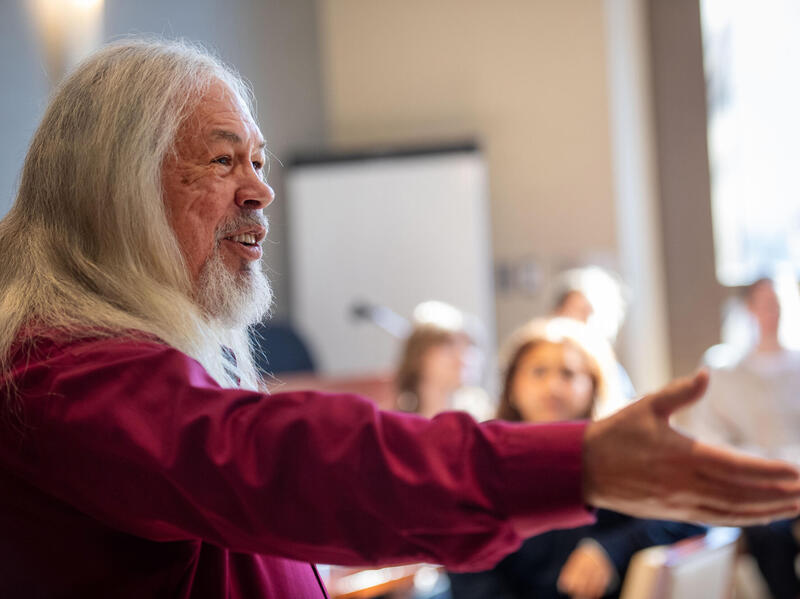

The study is the latest effort from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium’s Cross-Disorder Working Group, co-chaired by Kenneth Kendler, M.D., a professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Virginia Commonwealth University’s School of Medicine, and Jordan Smoller, M.D., a professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

The majority of people diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder will ultimately be diagnosed with a second or third disorder in their lifetime, creating challenges for defining and treating these conditions. While a person’s environment and lived experience influence their risk for developing multiple disorders, their genetic makeup can also play a significant role.

By analyzing data from over 6 million individuals, the working group mapped the genetic landscape of 14 psychiatric conditions and revealed five families of disorders with high levels of genetic overlap. The results mark an important step toward understanding the genetic connections among psychiatric disorders and could ultimately help clinicians better serve their patients.

“Psychiatry is the only medical specialty with no definitive laboratory tests. We can’t give a blood test to tell whether someone has depression – we have to rely on symptoms and signs. And that’s true for almost every psychiatric disorder,” said Kendler, a world-renowned researcher for his pioneering studies in psychiatric genetics. “Genetics is a developing tool that allows us to understand the relationships between disorders. The findings from this study reflect the most comprehensive analysis of psychiatric genomic data to date and shed new light on why individuals with one psychiatric disorder often have a second or third.”

For this study, the research group analyzed genetic material collected from more than 1 million individuals with a childhood- or adult-onset psychiatric disorder and 5 million individuals without a disorder diagnosis. By pinpointing genetic markers found more frequently in people with a particular condition, researchers can understand the genetic factors that contribute to these diseases.

The working group then used multiple complementary analytic approaches to dissect the genetic architecture of 14 psychiatric disorders and identify conditions with high genetic overlap. Their analysis identified 428 genetic variants associated with more than one disorder, as well as 101 regions on chromosomes that were “hot spots” for these shared genetic variants.

Through statistical modeling, the researchers found that the 14 disorders could be divided into these five groups based on genetic similarities:

- Compulsive disorders: obsessive-compulsive disorder, anorexia nervosa and, to a lesser extent, Tourette disorder and anxiety disorders.

- Internalizing disorders: major depression, anxiety disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Neurodevelopmental disorders: autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and, to a lesser extent, Tourette disorder.

- Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder

- Substance use disorders: opioid use disorder, cannabis use disorder, alcohol use disorder and nicotine dependence.

Major depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder showed especially high levels of genetic overlap, with about 90% of genetic risk estimated to be shared across these three conditions. Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder share about 66% of their genetic markers.

Through this study, the researchers also discovered that disorders with high genetic overlap also showed similarities related to when shared genes were expressed during human development and which brain cell types were impacted. For example, genes expressed in oligodendrocytes, a key part of the central nervous system, were more prominent in internalizing disorders, while genes expressed in excitatory neurons, which activate other neurons, were more prominent in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

The researchers say these findings provide a solid scientific basis for how the psychiatric field defines disorders, and the study could inform future efforts to create or repurpose therapeutics to treat conditions that commonly occur together.

“I feel very proud to be a part of this effort,” Kendler said. “This work really shows that we gain more for our field and for those suffering from mental illness when we come together to tackle these scientific challenges.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.