Feb. 4, 2010

VCU Professor a Virtuoso of Cinematic Effects

Share this story

When Matt Wallin was 7 years old, he saw “Star Wars” in a movie theater. Wallin, like just about every other kid who experienced the film during its initial run, exited in a state of giddy awe. He was stunned by the vivid realization of a fanciful world enlivened by space travel, strange creatures and the mystical Force. However, while most of his peers subsequently trained their focus on the spectacle itself, Wallin also grew enamored with the invention of that spectacle, eagerly consuming whatever he could find of the behind-the-scenes arcana that explained just how the director George Lucas and his team of moviemakers did what they did.

More than 30 years later, Wallin, now a veteran visual effects man and an assistant professor of communication arts in the VCU School of the Arts, has retained that fascination with the intricacies of films. Light bedside reading often means highly technical books on the latest in computer software and cameras. During the commute from his home in Charlottesville to VCU, he listens to podcasts about how special effects on newly released movies have been engineered. He attends conferences to sit in on panel discussions and presentations and reads the transcripts if he cannot be there in person. When he sees a movie with effects that impress and surprise him, he peppers his friends who worked on the movie – because, invariably, he knows someone who worked on it – with questions about the techniques they used. “Avatar,” the 3-D film breaking box office records, is a current obsession, especially the use of a groundbreaking lighting technique called spherical harmonics.

Wallin’s continuing headlong pursuit of knowledge has paid off. His resume credits include visual effects work on a host of Hollywood blockbusters dating back to the mid-1990s, such as “Star Wars Episode 1: The Phantom Menace,” “Twister,” “King Kong,” “The Lost World: Jurassic Park 2,” “Watchmen,” “I Am Legend,” “Matrix: Reloaded,” “Matrix: Revolutions,” “Hellboy” and “The Mummy.” He also has served as visual effects supervisor for the artist Matthew Barney since 1996, including managing effects on three of the films in Barney’s renowned Cremaster cycle.

Wallin’s path has sometimes involved risky choices – such as leaving a lucrative job at the top effects company in the world – and has taken him in surprising directions – he never envisioned himself as a professor – but the upshot has been a rewarding career that keeps him motivated and always hungry to learn more.

“I’m interested in a lot of different things – a broad base of technology and art and a bit of science – and I get to work on all of them,” Wallin says. “So far in my professional life, it’s been about looking at the things that I’m really passionate about and basically not talking myself out of them.”

Movie Magic

Wallin’s clip reel, a sample compilation of effects he has had a hand in producing, shows movies at their most visually thrilling, illustrating not only Wallin’s craftsmanship but the range of invention that is available to filmmakers today. There is little that they cannot convey on screen.

For instance, from Wallin’s clips, which can be found on his Web site -- http://www.mattwallin.com:

A strange flying ship bursts through the still surface of the Hudson River at night, sending an erupting spray of water high into the air. A shadowy moon is perched over the lit Manhattan skyline in the background. (“Watchmen”)

A visibly disturbed King Kong lopes down a 1930s New York City street, frantic pedestrians and vehicles rushing all around him. (“King Kong”)

Explorers fight giant scampering spiders in an oversized jungle. (“King Kong”)

A hideous zombie screams and rolls its sinewy head and neck, tendons bulging in striking detail. (“I Am Legend”)

The warrior Beowulf battles a giant dragon, swinging high in the air alongside the beast with his sword gripped in his hand. (“Beowulf”)

The Jedi knights Qui-Gon Jinn and Obi-Wan Kenobi clash with the sinister Darth Maul in a flash of light sabers. (“Star Wars Episode 1: Phantom Menace”)

The actor Brendan Fraser fights a gang of skeletons, using his sword to decapitate one foe and then swat its bouncing, screaming skull directly at the screen. (“The Mummy”)

The actor Keanu Reeves shoots a stream of fire from an ancient-looking gun. (“Constantine”)

Hellboy slugs a tentacle-headed alien, sending him crashing to the ground. (“Hellboy”)

A spaceship races through a narrow passageway, pursued by screaming tadpole-like creatures, sparks following it as it skids on its sides. (“Matrix: Revolutions”)

New York’s Chrysler Building: first imagined under construction and then, surreally, as a maypole. (“Cremaster 3”)

Advances in digital technology have democratized the art form of filmmaking, allowing cash-strapped students to produce work that would have been far beyond their budgets a few years ago. Now, Wallin says, it’s conceivable to take $15,000 and make “the best movie the world has ever seen.” Wallin is energized to be a part of this dramatic shift, including working on new techniques with students, such as those he teaches in a 3-D computer animation class.

“It’s a really exciting time,” Wallin says. “There’s just so much going on right now that is new.”

Managing visual effects involves creating or manipulating lifelike images that can be incorporated seamlessly into existing live-action footage. The field’s practitioners need a high level of skill and a fussy attention to detail. There is a range of specialties within the discipline – lighting, rendering, animation, structuring, compositing, etc. – and a complex visual effect typically involves a team of people laboring on an array of high-powered computers, each person obsessing over one aspect of the effect. In recent years, Wallin has worked as a digital compositor on films, bringing together the completed work of the various specialists into a cohesive, finished scene.

The work can be both exhaustive and exhausting. Wallin’s most intense job was the six months he spent in New Zealand working on director Peter Jackson’s re-make of “King Kong.” Wallin recalls working steady, 110-hour weeks for the final three months of the project alongside co-workers putting in the same hours, signs of gradual physical and mental deterioration evident as they raced against their deadlines. Of course, the rewards can be great. Wallin speaks with pride about the resulting effects in the film, such as the vigorous, lifelike movements of the giant gorilla at its center. “King Kong” earned an Academy Award for visual effects.

An Education in Effects

Wallin was not a tech geek in college. In fact, he did not even own a computer during his time at San Francisco State, where he majored in documentary and experimental filmmaking, instead banging out his scripts and papers on a Smith Corona typewriter. Visual effects interested him less than cinematography, screenwriting and camera work.

However, during his senior year, he landed an internship at Industrial Light and Magic (ILM), the visual effects company that George Lucas started in the 1970s, and worked in the art department, mounting storyboards and contributing in whatever way was asked. For his first shoot as a production assistant, he used a backhoe – a first for him – to clear land so that a knight could ride a majestic white horse through a meadow for an insurance commercial.

When the internship ended, Wallin finagled a one-year contract as the company’s receptionist. The job proved to be the ideal way for someone as ambitious and curious as Wallin to get his foot in the door. Wallin’s phone was the main line at ILM, making him the central hub of the company. Every one of the employees knew his name and he knew theirs. When his shift ended, Wallin was free to wander through the computer labs and watch how Lucas staffers were employing radical techniques to overhaul movie effects. They were working on “Jurassic Park” at the time and “were genuinely excited about what they were doing,” Wallin says. Most of his co-workers were only too happy to teach Wallin the tools of trade and even to let him sit in and work on projects. By the time his year was up as receptionist, Wallin was both entrenched and technically savvy. He was hired full time as a visual effects technician.

Lucas, the man who had inspired Wallin’s interest in filmmaking, was now his boss, reviewing his work and waiting alongside him in line for lunch in the company cafeteria. Meanwhile, Wallin had joined the vanguard that ILM then represented.

“They were changing so much at that time. Really, they were inventing the way that we see movies now,” Wallin says. “They created this big push forward during those years. While I was there, they went from having 250 employees to 1,500. I was very lucky to get that job and to be there at that time.”

Over the course of nearly seven years at ILM, Wallin worked as a computer graphics resource assistant on “The American President,” as a digital compositor on “101 Dalmatians,” “Twister,” “Speed 2” and “The Lost World: Jurassic Park 2,” and as digital artist on “Star Wars Episode 1: The Phantom Menace” and “The Mummy.”

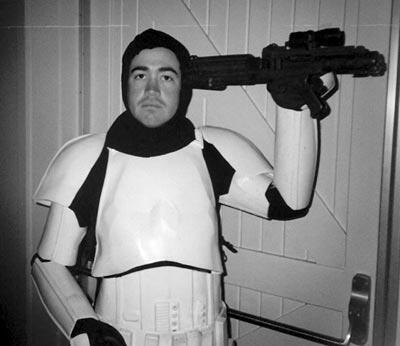

During Wallin’s tenure, Lucas created a special edition of “Star Wars,” utilizing computer-generated effects to add new scenes and enhance some of the old ones. Wallin was selected to serve as an extra, donning a stormtrooper suit and patrolling the Wild West-like streets of Tatooine. In a tidy bit of symmetry, Wallin became a physical part of the movie that had made him want to make movies in the first place.

Shift in Scale

The sheer size of the operation that creates a big-budget, effects-laden film can lead participants to feel a bit lost in the machine -- “it doesn’t take away from the fun of working (in visual effects) but it is hard to get a sense of ownership in the films sometimes,” Wallin says. Early in his time at ILM, Wallin demonstrated an urge to also work on smaller productions that would allow him a more substantial role.

Wallin had been struck by Barney’s first two Cremaster films, which reminded him of Star Wars “in a perverse way.” The graphics in the films were crude, and Wallin wrote Barney a letter expressing his admiration for his films and offering to help.

Barney took Wallin up on the offer, and Wallin has supervised visual effects for all of Barney’s films since, contributing such haunting elements as an ice floe in the Danube River and a computer-generated version of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. Wallin left ILM in 1999 and moved to New York to work full-time on "Cremaster 3," the final chapter of the film cycle, not only contributing visual effects to the film but manning a camera to shoot behind-the-scenes documentary footage. He and some colleagues started a small effects company soon after he arrived on the East Coast.

The two-and-a-half year "Cremaster 3" project had a major impact on Wallin both personally – during production he met his future wife, who was painting sets – and artistically. Whereas before Wallin largely had worked on movies from a computer lab, he was on the set every day for "Cremaster 3" and it gave him new insight into filmmaking.

“I learned where the creative impulse was coming from for each decision and how (Barney) was orchestrating everything,” Wallin says. “It was fascinating seeing the whole thing up close from beginning to end – the whole production. It was so much fun to be around.”

Wallin found he enjoyed his independence and he lived a peripatetic life after "Cremaster 3," working on projects in a number of locales, including his six-month stay in New Zealand in 2005 for “King Kong.” He moved to Charlottesville with his family in 2006 and was hired at VCU later that year after seeing the faculty opening advertised in an experimental film magazine.

Something New

Wallin radiates an infectious enthusiasm for movies and seems as interested in discussing others’ work as his own – a valuable trait in a teacher. In fact, it is easier for Wallin to watch others’ films because he does not see in each frame the strain and effort needed to make them. Wallin recently saw the disaster flick, “2012,” and was impressed with the film’s depiction of an earthly apocalypse. “Avatar,” though, merits a special praise from Wallin, who grows animated when he discusses its charms. The film has raised the bar for Wallin and his fellow effects professionals. Wallin says that when he saw the film in a Charlottesville theater the audience – a mixed group, he says, ranging from kids to middle-aged adults – broke into a spontaneous ovation at the conclusion of the film. “I don’t remember when I’ve seen that before,” Wallin says.

The post-production visual effects for “Avatar” were managed at Peter Jackson’s Weta Digital facility in New Zealand. Many of the same people that Wallin toiled alongside on “King Kong” worked on “Avatar,” too, and he was in touch with them during production, consuming their stories about the making of the film.

If he had chosen differently and remained in New Zealand – a country he loved – Wallin likely could have been a part of the “Avatar” phenomenon, too. Still, Wallin does not regret leaving the rush of steady visual effects work. He now accepts projects that fit his schedule and allow him to stay close to his wife and young son. Two summers ago, the three of them moved to Vancouver for 14 weeks so Wallin could work on “Watchmen.” He also took a semester off to work on “Beowulf” and “I Am Legend” and worked on visual effects for Barry Levinson’s film, “Man of the Year,” from his home studio.

“I sometimes miss that camaraderie of like-minded (film nerds) working really hard together on something,” Wallin says. “But that’s replicated in some ways in the lab here with students.”

Wallin’s next direction might involve a new role in a movie’s development – one that echoes his studies in college. He has been working on the screenplay for a narrative film. His description of the plot – which he says is not ready for publication – is beguiling. The movie will rise and fall on a central, conflicted character, but when Wallin tells the tale he does not fail to sketch a few scenes that beg for memorable visual effects. It would be hard to leave those out.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.