Feb. 18, 2019

For billions, clean water is scarce. For one week, it was for these VCU students too.

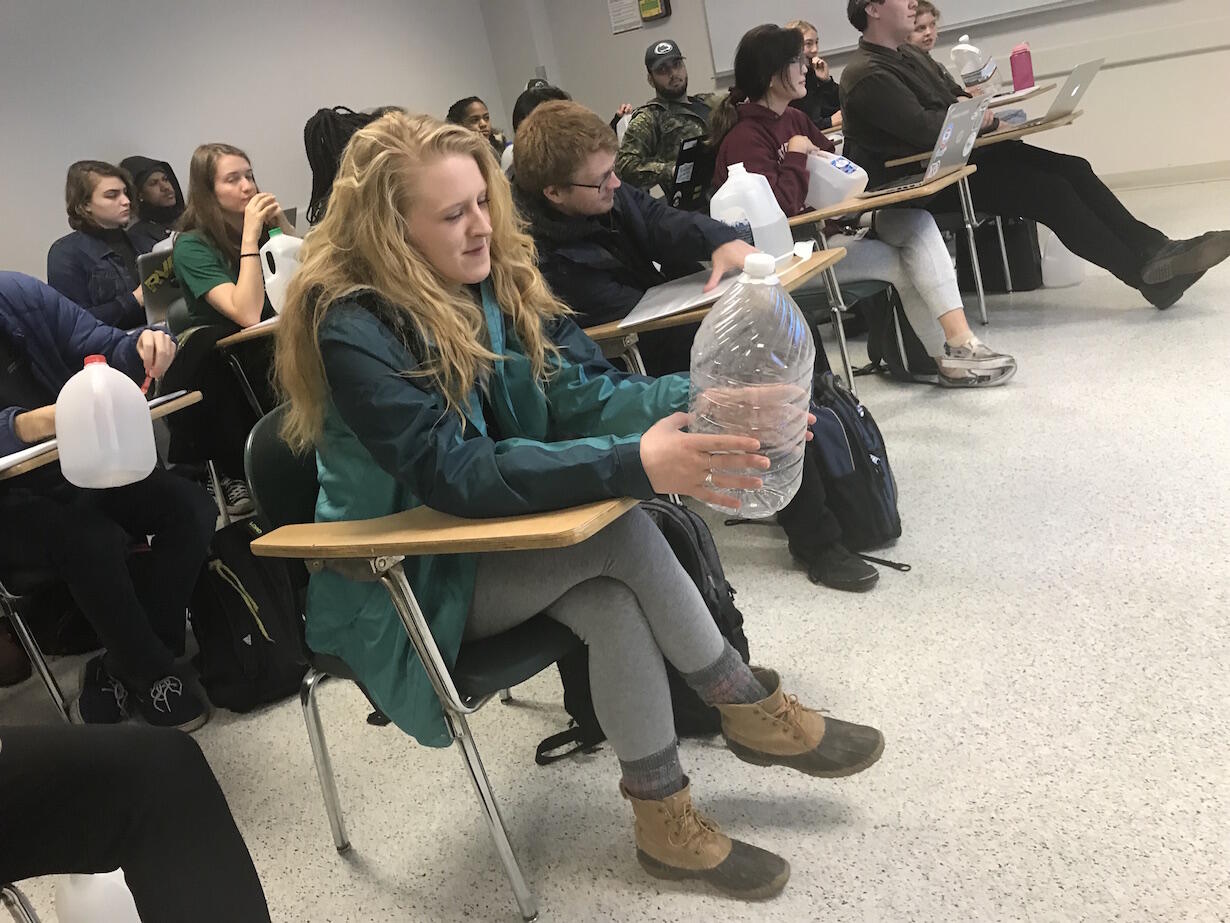

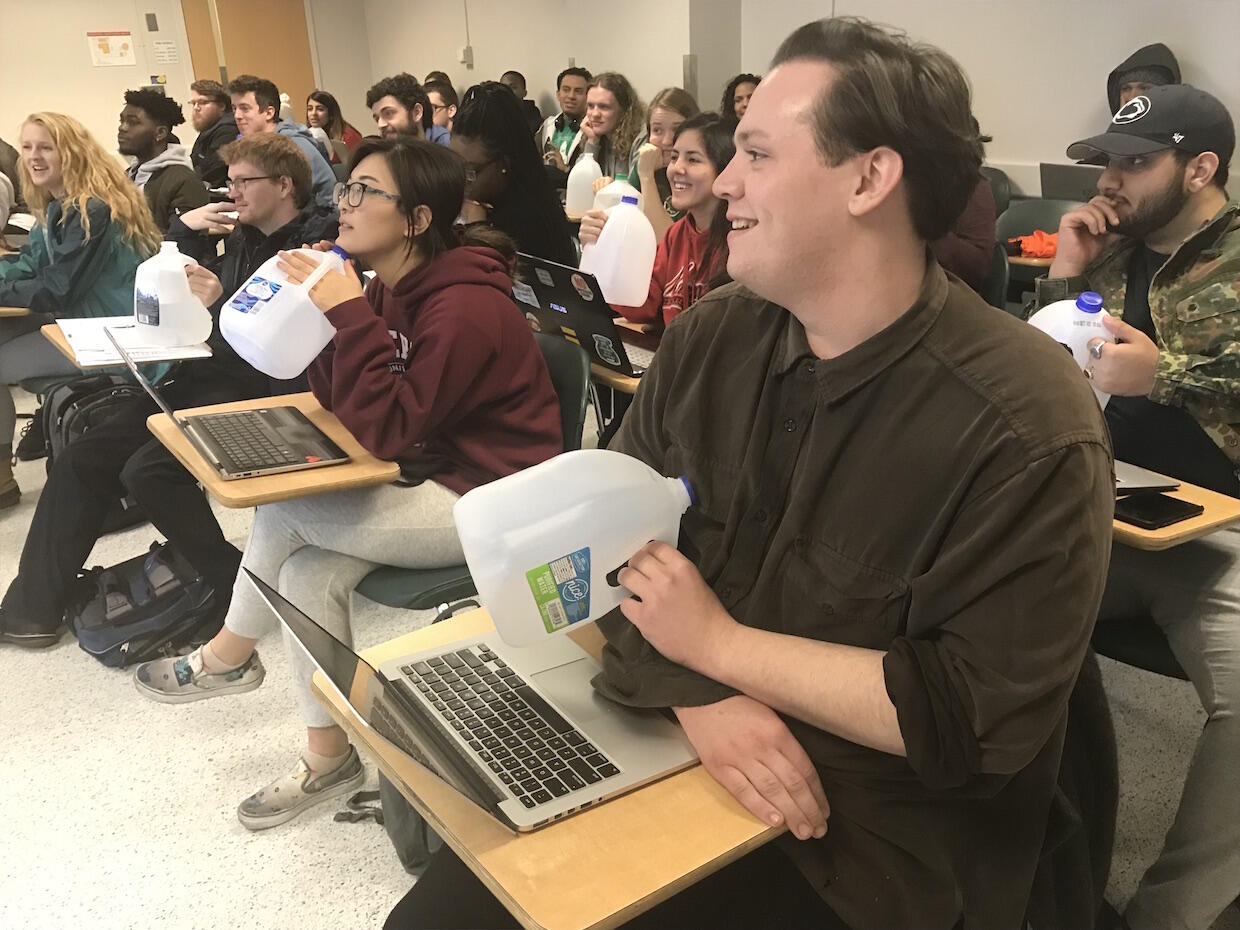

To gain insight into life where clean water is not easily accessible, students in a VCU political science class were put on a tight water diet last week.

Share this story

All water that Virginia Commonwealth University student Raphael Debraine has consumed over the past week — to drink, cook, wash his hands, make coffee, brush his teeth, wash dishes or shave — had to be drawn from an on-campus water fountain into a gallon jug, and then lugged home via a 20-minute walk to his apartment in the Fan.

“Oh, it sucks,” Debraine said. “It sucks so hard. It’s horrible.”

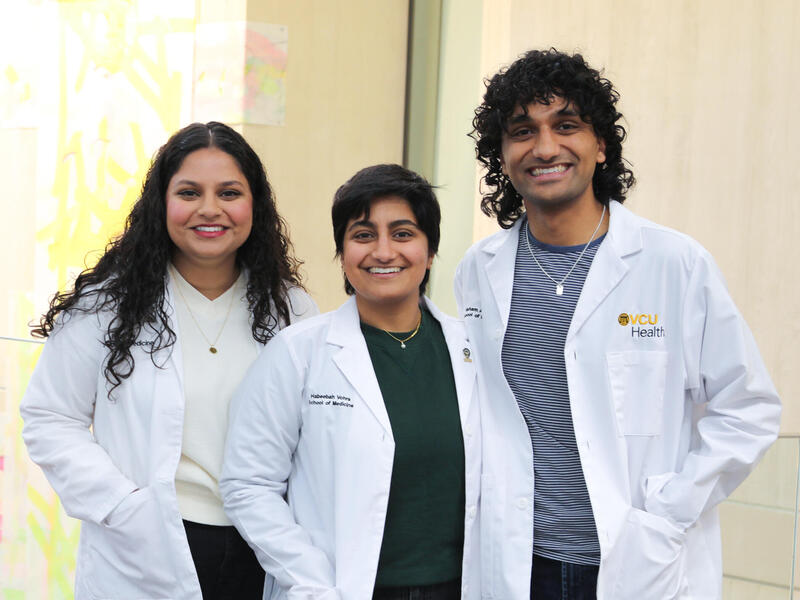

Debraine, a senior studying political science, and his classmates are taking the course Environmental Security, taught by Andrea Simonelli, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science in the College of Humanities and Sciences. The students were assigned to spend all last week on a tight water diet.

The idea is to provide insight into the daily struggles faced by the billions worldwide who lack easy access to clean drinking water.

“Globally, 2 billion people have to use drinking water contaminated with feces. In 41 countries, a fifth of people drink water from a source that is not protected from contamination,” Simonelli said. “And in sub-Saharan Africa, people spend between 30 minutes and one hour a day collecting water.

“For this assignment,” she told her students, “you will be one of them.”

A few days later, students like Debraine were learning to adapt.

“The first day I went home and made [hamburgers] and I realized just how much water I use just for one meal. When I cook, I’ll use multiple bowls for different spices, I’ll use different knives and different cutting boards. And I never really thought about the water that’s used in washing those,” Debraine said. “By the time I was halfway done with the dishes, I’d used up my entire gallon.”

The next day, Debraine started cooking dishes, such as rice and fish, that required fewer pots and pans.

He also switched up his daily commute. Normally, he rides his bike to campus. Last week, he opted to walk so he could more easily carry his water jug, remembering that Simonelli had warned the class about a student a few years back who had fallen off his bike while trying to carry his heavy, sloshing jug.

Globally, 2 billion people have to use drinking water contaminated with feces. In 41 countries, a fifth of people drink water from a source that is not protected from contamination. And in sub-Saharan Africa, people spend between 30 minutes and one hour a day collecting water.

Other students encountered different challenges. One student’s jug leaked in his backpack, soaking its contents. Another accidentally kicked his over during class, spilling a bit of water. One had to ask classmates for advice on how to wash dishes using minimal water.

A student who works at a Richmond restaurant had to strategize how to best wash her hands during the week, particularly given that it was occurring the same week as the restaurant industry’s busy Valentine’s Day rush.

“This is torture,” complained one student who lives off campus, as Simonelli explained the exercise.

“This is not torture,” Simonelli replied. “You live in America. By virtue of birth, this is not your normal life. You will live [doing this exercise] for a week. This is not supposed to be easy. This is supposed to be inconvenient. You know what it’s called when people have to spend 30 minutes to an hour a day collecting water? It’s called inconvenient.

“It is absolutely inconvenient to be water scarce,” she said. “But this will help you understand how much productivity and how much of people's lives — most people who are not unlike you — get spent having to do basic things. You know what is basic? Drinking. And we all need to do it every day without even thinking about it.”

Choices, trade-offs and extra steps

For many of the students, the exercise gave them a better understanding of the choices, trade-offs and intellectual labor involved when one cannot simply draw clean water from a household tap.

“It’s been interesting,” Debraine said. “It adds an extra step, where I’m always thinking about what I’m going to do. Do I need to go back to VCU now? Yes, I need to fill up my water. What am I going to make for dinner? I can’t make pasta because I'm not going to go back to VCU to get more water. It’s that extra step of thinking ahead and planning that you don’t really have to take when water is easily available.”

The exercise is inspired by Simonelli’s field work in countries such as the Polynesian island of Tuvalu, which experienced a severe water shortage in 2011 caused by a major drought. She visited Tuvalu last summer, along with Samoa, Fiji and the Marshall Islands, as part of her research into how governance affects climate resilience through human security in the Pacific.

Simonelli, the author of “Governing Climate Induced Migration and Displacement: IGO Expansion and Global Policy Implications” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), is an expert in human migration and displacement brought about by climate change.

“I go to all kinds of places where getting access to clean water is not convenient,” she said. “This [exercise is similar] to what I have to do. It is not easy. You have to carry your water. You have to shower awkwardly. These are my challenges when I travel and when I do field work.”

Simonelli’s Environmental Security class explores not only how the availability of natural resources affects human civilization, but also how we artificially determine their accessibility through means of political power. In addition to water scarcity, it covers topics such as food security, air quality and habitable zones, and also explores issues at the nexus of resource conflict, including privatization, scarcity, over-usage, competing interests, garbage, climate change, gender issues, migration, forests and disaster.

“This [water scarcity] exercise fits into the course in that it is an experiential way that the students can connect with the case studies that they are learning about,” Simonelli said. “The majority of Earth's inhabitants are water insecure in either it’s hard to find or unclean. Students can feel removed from these experiences, or simply pity, unless they actually try for themselves to live in these conditions.”

The lack of easy access to clean water, Simonelli told the students, can have impact in ways large and small.

“It’s often cheaper to buy soda than it is to buy a bottle of water,” she said. “Once you process all that water, you’d think that would make it more expensive. But it’s not. So, oftentimes in the places that I work, you’ll see more of the locals drinking sugary drinks than you see them drinking water. And consequently, there are very high levels of people with diabetes [because they have] a diet full of rice and sugary drinks.”

‘Usually the students hate me at first’

Not all water consumption was included in the exercise. The students were allowed to take showers (to be considerate to roommates) and do laundry.

Throughout the week, the students were required to write daily diary entries that documented their experiences and kept track of all water usage.

Simonelli told the students she expected them to struggle, forget, fail occasionally and even cheat.

“I want to know: What did you do?” she said. “This is about the difficulty of learning how tough it is to do this. I want to know what you did. I’m not marking you down because you got in a bind. I want to know what happened and how you tried to avoid it.”

Simonelli, who has two similarly challenging assignments in store for her students later this semester, said the water-scarcity exercise might prompt complaints, but ultimately provides students with a deeper level of understanding.

“Usually the students hate me at first,” she said. “But when we go over all of the grander implications of water insecurity and then we talk about their shared experiences, they usually appreciate it — and their sinks.”

For Jasmine Parks, a public relations major in VCU’s Richard T. Robertson School of Media and Culture, the project led her to think about how much water and other resources she consumes, and to appreciate the conveniences that come with living in the United States.

“I know I take things for granted, especially how good my life is. We all complain about our lives — I know I do — but I just have to reassure myself that I have it way better than most people do,” she said. “This project really puts everything in perspective and is reminding me to be truly grateful for what I have.”

It also gave Debraine a new perspective on water and consumption.

“The sadistic part,” he said, “is just seeing how slowly the jug fills up and how quickly it empties out.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.