Aug. 15, 2016

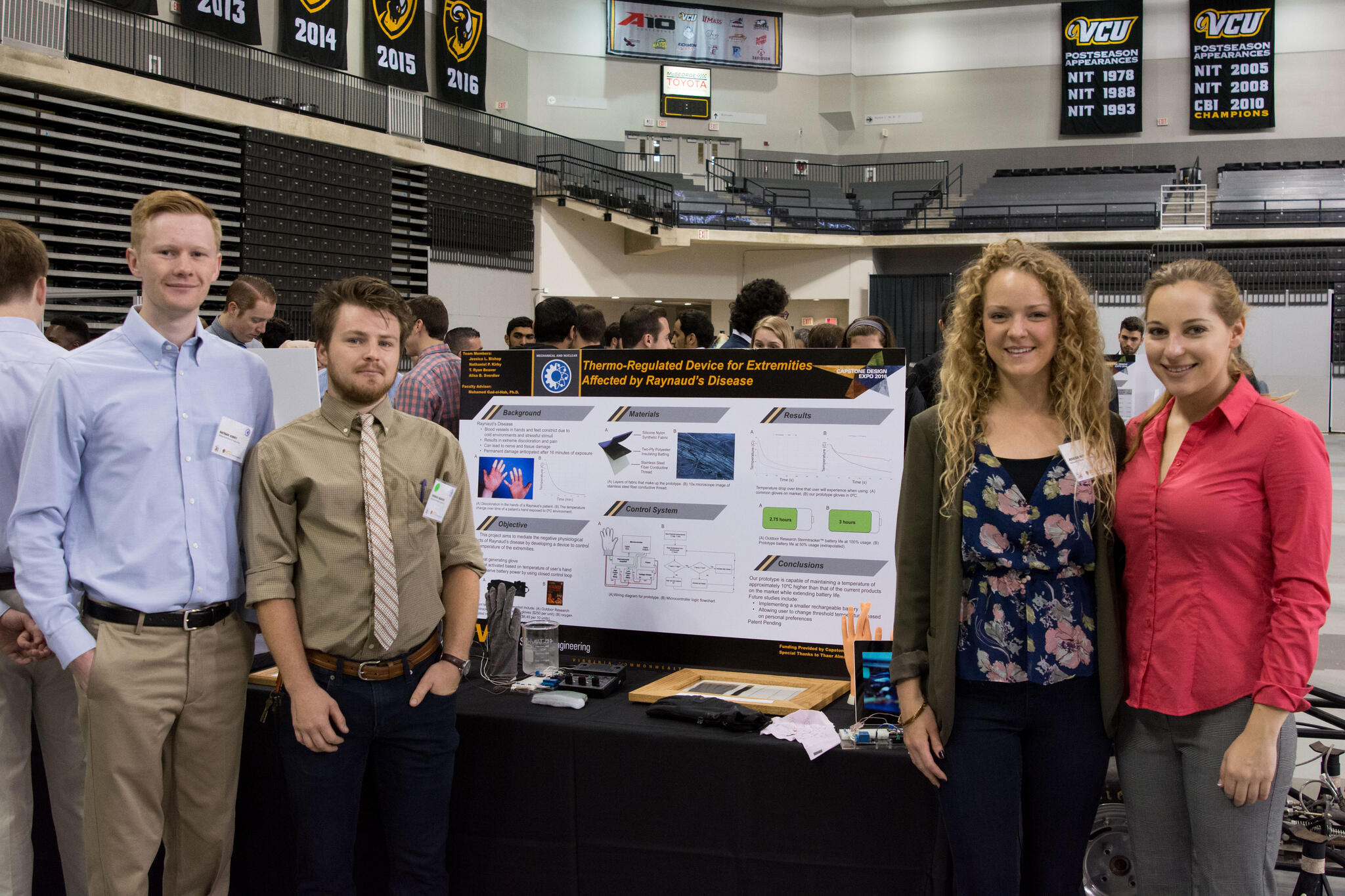

Engineering students design thermoregulated gloves that help people with Raynaud’s disease, including one of their own

Share this story

Every time Jessica L. Bishop suffered an attack of Raynaud’s disease during her senior year at Virginia Commonwealth University, it motivated her to work even harder on her School of Engineering Capstone Design project, a pair of “magic gloves.”

The gloves help regulate the fingers’ temperature, which is relevant because Raynaud’s disease affects extremities in such a way that people with the condition are unable to tell when their hands get cold, among other symptoms.

“It’s something I’m very passionate about. It’s something that definitely affects me,” Bishop said. “There’s a slew of medications that they can put you on, like blood pressure medication, [but] there’s nothing specific to the Raynaud’s. It’s really just remedying the symptoms [by] wearing gloves, avoiding cold, avoiding stressors. Not drinking a lot of coffee.”

Typically, blood flows from your heart to all the parts of your body, keeping them warm, said T. Ryan Beaver, one of Bishop’s Capstone teammates.

“This disease attacks the path that blood flows on and constricts it so the blood can’t keep flowing, so your fingers and toes don’t warm,” he said.

Someone without Raynaud’s disease can tell if his or her fingers or toes are dangerously cold because it hurts, Beaver said. Without that pain, you wouldn’t know if your temperatures are reaching the danger point where tissue damage or frostbite can occur. And then once the attack is over and blood starts flowing again, you suddenly feel the pain.

“Frostbite can happen really quickly, again without the person knowing,” Beaver said. “Other tissue damages can lead to amputation and infection. A lot of nasty things.”

Nuclear engineer Nathan Kirby — the first classmate to join Bishop’s team — spent countless hours over his senior year coding and running simulations. Modeling the way a hand’s temperature would drop when exposed to zero degrees Celsius, he determined that permanent nerve damage could occur after 16 minutes of exposure.

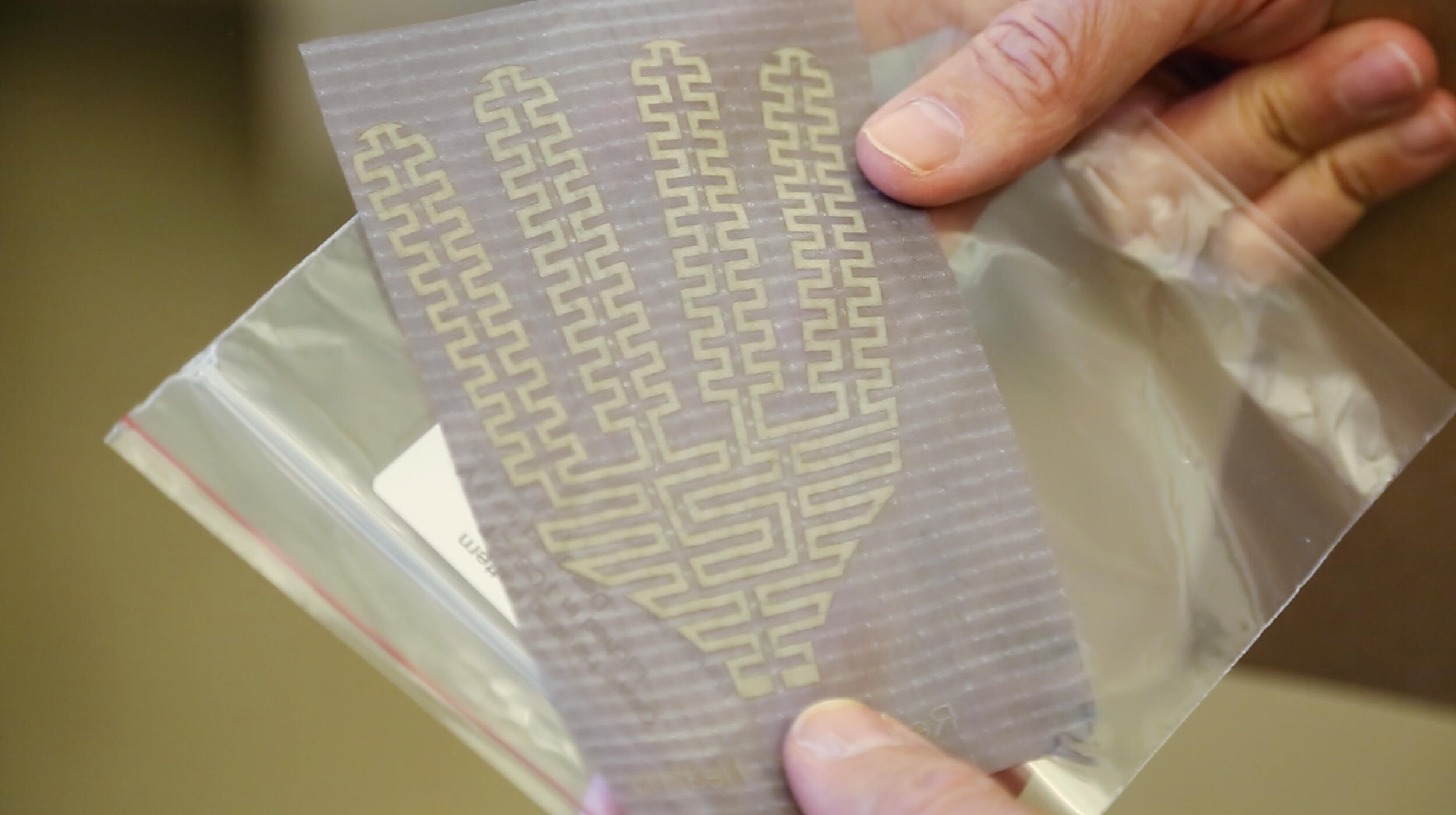

A special fiber sewn into the magic glove, which is properly known as a “thermoregulated device for extremities affected by Raynaud’s disease,” heats up when electricity is applied. A controller with a thermometer sits in the glove’s fingertips. When temperatures reach a dangerous level, the controller turns on one of two heaters. A low-powered heater keeps the wearer at a safe temperature. If the temperature falls below that, the high-powered heater kicks in. But, if the temperature rises too much, the heater turns off so the wearer doesn’t sweat.

With so much equipment, you would expect the gloves to be incredibly heavy, compromising flexibility for heat. Not so, said teammate Alisa Sverdlov.

The inside layer of the gloves can be removed from the outside layer, so people can wear them indoors while working at a computer and still have dexterity, she said.

Anyone who spends time in the cold can benefit from these gloves. Sverdlov said she can’t type in cold offices and looks forward to using the gloves in such an environment.

Mohamed Gad-el-Hak, Ph.D., said he was thrilled to serve as faculty adviser for the project.

“What attracted me to the project is Jessica’s positive attitude about channeling a personal adversity into doing something to help all of humanity,” said Gad-el-hak, the retired Inez Caudill Eminent Professor in the Department of Mechanical and Nuclear Engineering. “Students like that is what makes it all worthwhile, not to mention life worth living.”

Bishop was diagnosed with Raynaud’s at 14. It has gotten progressively worse over the years, especially in winter. At first, she didn’t take her cold hands and feet seriously.

“Then they started turning white. And then [they] started hurting,” she said. “And every year it would get worse and worse. It’s in your autoimmune system, so when you’re exposed to cold or stress, your arteries actually constrict and the blood flow doesn’t get to your hands. That causes nerve damage.”

In addition to the danger of Raynaud’s, Bishop finds it hard to explain to someone when she’s “Raynauding,” because the disease is invisible.

“It’s so uncomfortable and you can’t explain that to someone else,” she said. “It really takes mental focus keeping that separate from your life.”

While heated gloves exist, none work as well as VCU’s, Beaver said. The university has received a provisional patent for the magic gloves and is seeking a private sponsor to file for a permanent patent.

“We’ve compared our glove to the industry-leading glove right now, which isn’t as smart as ours,” Beaver said. “[Ours] stays 10 degrees warmer while maintaining a longer battery life.

A lot of gloves on the market don’t heat the back of the hand entirely, Bishop said. She pointed out a $300 glove that she used to wear in the lab but noted that it was too bulky to be comfortable and caused her hands to sweat profusely.

“It gets so hot and there’s no regulation,” she said. “It’s just the heating glove where ours actually registers and regulates [temperature].”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.