Sept. 20, 2021

Variants, misinformation, vaccine hesitancy: Jeanine Guidry’s work is more crucial than ever

Share this story

She didn’t know it at the time, but Jeanine Guidry, Ph.D., had been preparing for COVID-19 for years.

Guidry, an assistant professor in the Richard T. Robertson School of Media and Culture in the College of Humanities and Sciences and director of the Media+Health Lab at Virginia Commonwealth University, studies social media and health communications, focusing particularly on effective public messaging in a health crisis.

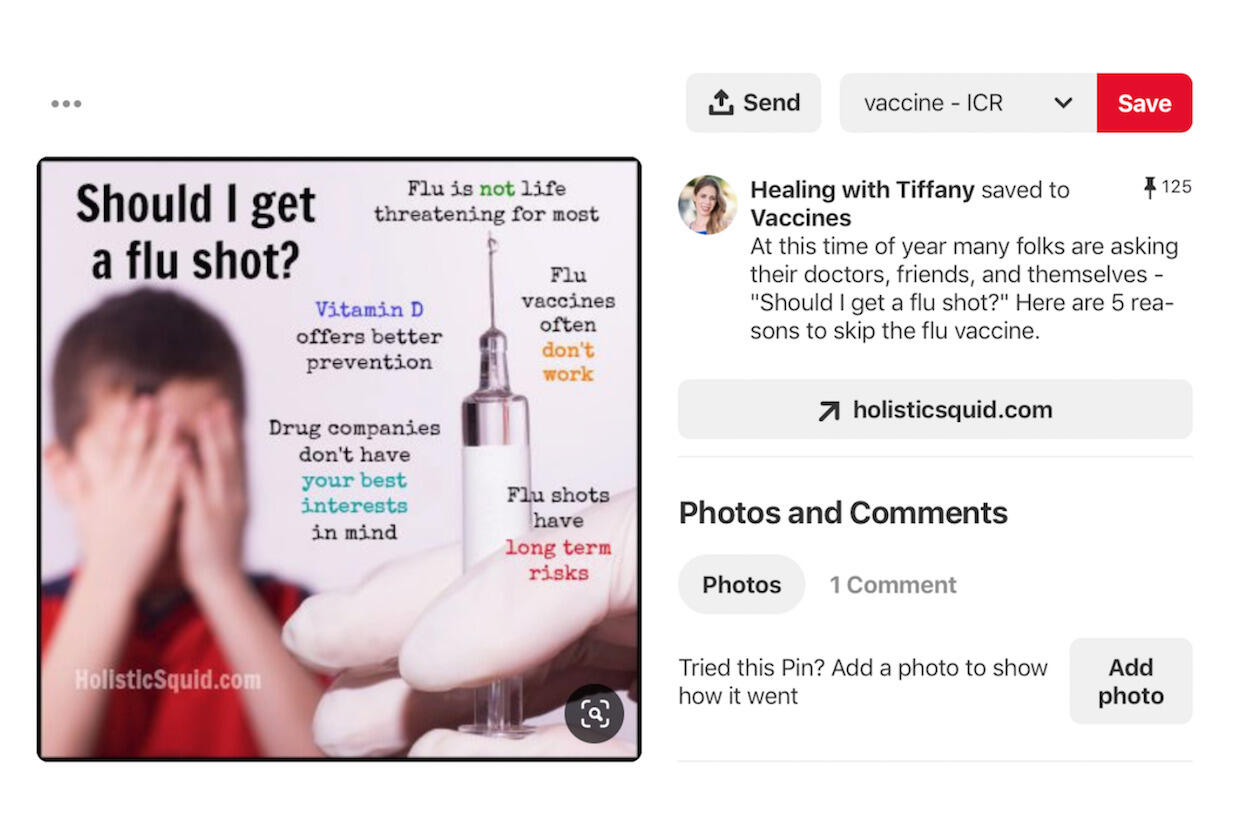

Her doctoral dissertation, “Designing Effective Messages to Promote Future Zika Vaccine Uptake,” explored how public health officials could best encourage people to be vaccinated against Zika virus, should a vaccine become available. She led a study, “(S)pin the Flu Vaccine: Recipes for Concern,” that analyzed 500 flu-vaccine Pinterest posts, providing insight into how misinformation can proliferate on social media. During major Zika virus outbreaks in 2016, Guidry collected and analyzed 1,000 Instagram posts to understand how public health messaging works — and doesn’t — amid a dangerous epidemic.

“On one hand, I feel very grateful to be in the position that I’m in and to be alive right now,” Guidry said. “I’ve been getting ready for this for years. I didn’t know that, but I have been. And I play a very small role, like most scientists do, but all those little small pieces of information that we didn’t have before come together and begin forming a picture.”

As soon as COVID-19 arrived, Guidry pivoted to focus on the new coronavirus. In March of 2020, she created and began teaching a new three-credit course, “Digital Crisis Communications for Global Pandemics.”

“I started thinking about it on March 20, and then on March 30 the class started. We’re still teaching it,” she said. “I’m not sure I would recommend developing a brand new course in 10 days, but I’m glad we did it.”

Her research quickly turned to COVID-19 as well.

Prior to the pandemic, she had received a grant from the Arthur W. Page Society to study messaging about the flu vaccine. In March 2020, the organization gave her permission to study COVID-19 instead. That study, “Stay Socially Distant and Wash Your Hands: Using the Health Belief Model to Determine Intent for COVID-19 Preventive Behaviors at the Beginning of the Pandemic,” involved a survey of 500 adults. It looked at how likely they would be to adhere to preventive behaviors that were recommended at the time, such as not touching one’s face, social distancing, avoiding large gatherings and staying away from those who were sick.

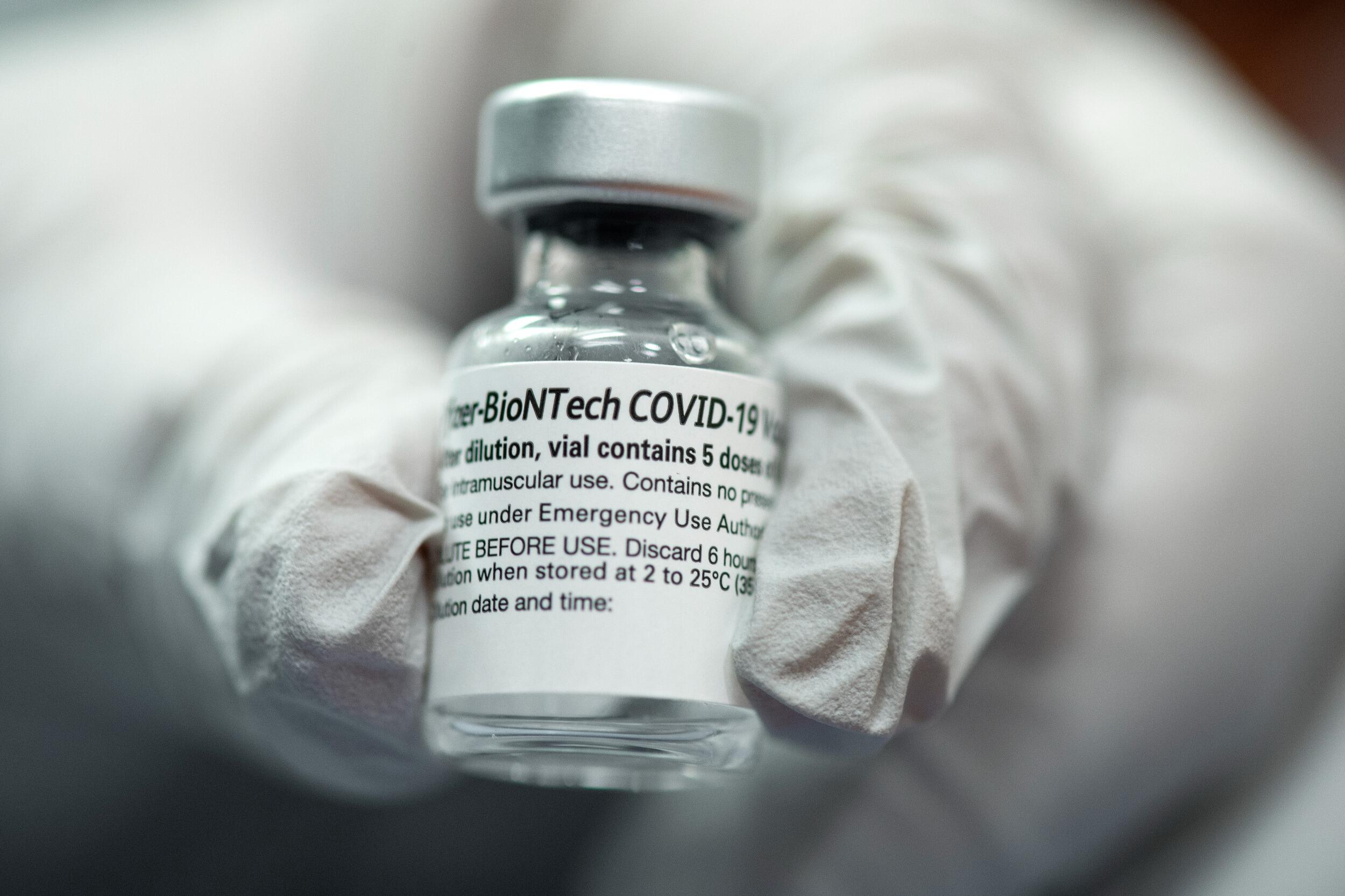

In December 2020, as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine under emergency use authorization, Guidry published a study that was among the first to investigate the psychological and social predictors of U.S. adults’ willingness to get a future COVID-19 vaccine and whether these predictors differ under an emergency use authorization.

“I realized pretty quickly that while we’re in the midst of this outbreak, we need to not just figure out how to develop a vaccine but also figure out how people would receive it,” Guidry said. “Because the vaccine is only as good as the shots in people’s arms.”

That July 2020 study, “Willingness to Get the COVID-19 Vaccine with and without Emergency Use Authorization,” involved a survey of 788 adults. It found that 59.9% of respondents were definitely or probably planning to receive a future coronavirus vaccine, but fewer than half of respondents planned to get it under emergency use authorization. It also found that white people were more likely than Black people to be vaccinated.

Another study Guidry led, published in March 2021, used that same sample of 788 adults and was among the first to question whether the U.S. population would support donating part of its vaccine stockpile to low- and middle-income countries. That study, “U.S. Public Support for COVID-19 Vaccine Donation to Low- and Middle-Income Countries during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” found that older people, Republicans and the uninsured were less likely to support donating vaccines to less prosperous countries.

A study she led for Massey Cancer Center — where Guidry serves as a member of its Cancer Prevention and Control research program — found that parents of children with cancer were more likely to believe misinformation and unverifiable content associated with COVID-19 than parents of children with no cancer history. The study also analyzed Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data to show that pediatric cancer mortality has increased during the pandemic due to delayed access to medical care, with COVID-19 misinformation cited as a potential contributing factor.

“Dr. Guidry's work is very important right now. COVID-19 is an extremely complex challenge, and her research is key to understanding how information — and especially misinformation — about the pandemic is communicated,” said Jennifer Malat, Ph.D., dean of the College of Humanities and Sciences. “Dr. Guidry's findings have immediate real-world value as we strive to combat misinformation and will also be useful as we meet new health care challenges in the future.”

‘A science and art’

In late 2020, Arthur L. Kellermann, M.D., senior vice president for health sciences at VCU and CEO of VCU Health System, read about Guidry’s research and reached out.

“He sent me an email and said, ‘I need to talk to you.’ You know, this is Dr. Art Kellerman, who is the head of VCU Health, and I am a very junior faculty member. I mean, let’s be real. That doesn’t happen every day.”

Kellerman arranged for Guidry to take leave from teaching during the spring semester, allowing her to focus on her COVID-19 research.

“Effective communication is a science and art,” Kellerman said. “No one understands that better than Dr. Guidry. Her expertise is critical, now more than ever, because we’re not only fighting a relentless and deadly virus; we are fighting a relentless barrage of misinformation that is extending the life of this pandemic. Although the science of public health has never been stronger, we need to do more to inspire the trust and confidence of those we serve. Dr. Guidry’s research helps us do that.”

Guidry’s main project during the spring was the development of online decision aids, which will help people navigate the choice to get the COVID-19 vaccine. When the decision aids are rolled out in coming months, one will be aimed at the general public and another specifically for parents and children. Guidry and her collaborators are translating the decision aids into Portuguese and Spanish with plans to test them in South America in addition to the U.S.

“We’re very, very lucky that the vaccines, in general, work so far with the variants, but there’s a whole bunch of them that are popping up and that is what you get with a brand new virus,” Guidry said. “We know a lot more than we did a year and a half ago. And that is wonderful, but it also keeps changing. So these decision aids, we’re going to be able to test them pretty quickly and start using them and making them available for people to use. And hopefully they will help some people make a decision to get the vaccine.”

“Effective communication is a science and art. No one understands that better than Dr. Guidry.”

Arthur L. Kellerman

Also in early 2020, Guidry provided expertise to VCU Health as it developed strategies to encourage people to be vaccinated.

Her work with colleagues at the VCU School of Medicine — where Guidry received her Ph.D. in social and behavioral sciences from the Department of Health Behavior and Policy — and with VCU Health, she said, is a reminder of the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration and that “we are one VCU.”

“Our campuses may be a couple miles apart, but I believe that some of the most effective research is done when we work together and bring people together for things as big as COVID, but also climate change and other massive problems we’re facing,” she said. “To find solutions, we need everyone at the table.”

What’s behind vaccine hesitancy?

Among Guidry’s key findings related to COVID-19 are insights into why people are reluctant to be vaccinated.

It was not a surprise, she said, because there has been hesitancy with previous vaccines. But it was a surprise — particularly given the number of deaths, the visual reminders of masks, the recommendations to avoid crowds and stay away from loved ones indoors — that Guidry found many people do not consider COVID-19 a serious risk.

“The thing about vaccines is that it depends not just on: Are people convinced that the vaccine works? They also have to be aware of the disease and they have to be convinced that the disease itself is serious, and that they’re at risk or the people who they love are at risk,” she said. “One of the main findings, and we’re looking at different at-risk populations, there is, every time, whatever population you look at, a pretty significant percentage of people that say, ‘I don’t think COVID is that serious. I think that taking the vaccine is a greater risk or is a risk. And I don’t want to take that risk.’”

Another finding, Guidry said, is that many people are reluctant because of a fear of needles.

“Needle phobia pops up as a significant predictor of vaccine hesitancy almost every time we do a study,” she said. “There’s sufficient numbers of people in the samples that we study that say, ‘I just really don’t like needles.’ That’s a real thing.”

Knowing that, she said, public health messaging should try to avoid sharing photos of needles on social media or in advertisements. Guidry received national media coverage in the spring, including in Kaiser Health News, for the finding that a fear of needles was a significant predictor of people refusing the COVID-19 vaccine.

“If you’re really, really scared of getting the vaccine because of needles, we need to address that in an entirely different way than if somebody says I’m concerned that the Pfizer and the Moderna vaccines are going to change my DNA,” she said.

Yet another finding is that misinformation continues to spread on social media.

“I’m very grateful that social media platforms are really trying to make an effort. Let’s put it that way. I’m also thinking that we’re late with all that. We knew that social media was a breeding ground for misinformation, and especially misinformation about vaccines,” she said. “There are nefarious actors in this, but the majority of people who spread these pieces of misinformation are not, they’re truly people who are just scared, they’re concerned. They really think that this may hurt them or their family or their kids now, or in 10 years.”

The persistent COVID-19 misinformation, she said, is driven by a loss of trust in science and underscores the need for better communication.

“One of the things we see consistently when we look at what people say on social media, and in some cases what people say in our studies is, ‘Well, I did my own research and I found there are a thousand [deaths] every few days from the COVID vaccine, way more than from COVID,’” she said. “Here’s the problem: You can find that kind of information online. It’s not correct, but you can find it. So I don’t think we have done a particularly good job as a society in making sure that people understand how science works and how it should be communicated.”

One key takeaway, Guidry said, is that encouraging someone to get vaccinated is probably best done person to person and not over social media.

“It starts with listening to each other and it starts with keeping lines of communication open,” she said. “If you’re going to have a conversation with someone about [getting vaccinated], try and do it in person, or try and do it over private chat or over a phone call. People may not be willing to listen right now, but maybe they will in three months. And if that line of communication is closed, then how do we get past that?”

Interdisciplinary collaboration

Guidry has a number of forthcoming studies that she conducted with a team of collaborators that includes researchers at VCU across both campuses, such as Paul Perrin, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Department of Psychology; Mark Ryan, M.D., an associate professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health; Kellie Carlyle, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Department of Health Behavior and Policy; and Bernard F. Fuemmeler, Ph.D., a professor and associate director for population science and interim co-leader of the Cancer Prevention and Control research program at Massey Cancer Center.

The team also includes partners outside VCU, including Candace Burton, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Sue & Bill Gross School of Nursing at the University of California, Irvine; Linnea Laestadius, Ph.D., an associate professor at the School of Public Health at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; Emily Vraga, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Minnesota; and Thomas Gültzow, a doctoral candidate and decision aid specialist at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, Guidry’s alma mater.

One forthcoming study looks at the response to COVID-19 and vaccines among people who self-identify as evangelicals. Another will explore vaccine perceptions among people who are not white.

“So we want African Americans, we want Hispanics. We want Asian Americans, we want Native Americans. Why? Because we’re still dealing with the fact that people of color tend to be more affected by COVID; when they’re affected by COVID, they’re affected more seriously; and this is a pattern that we see happen again and again. … So we need to do more to find out why could that be the case,” Guidry said.

“Is there anything that would make a difference? Is there any insight that could be gleaned from this that would make it a little bit better?” she said.

“Here’s the problem: You can find that kind of information online. It’s not correct, but you can find it. So I don’t think we have done a particularly good job as a society in making sure that people understand how science works and how it should be communicated.”

Jeanine Guidry

Another forthcoming study will look at how college students responded to COVID-19, particularly with social distancing. The study, which involved focus groups and surveys, included students from VCU as well as six foreign universities, including one in Wuhan, China.

A similar study, launched at the request of the State Council of Higher Education of Virginia, explores why young people in Virginia are one of the least vaccinated populations. Guidry and her collaborators held focus groups and conducted surveys, asking young people why they were choosing not to get vaccinated.

“It was just remarkable and scary, hearing all the same type of misinformation,” Guidry said. “[They said] ‘I heard it messes with fertility. I want to have babies.’ No, it doesn’t. It really, really, really doesn’t. But knowing that kind of misinformation is out there, I think, gives us some more specifics on how we can communicate.

“We’ve got to find better ways to communicate specifically, and we need to find more culturally appropriate ways to communicate,” she said. “In a perfect world, we would make sure that these pieces of misinformation never take hold, but that ship has sailed.”

Preparing for the next pandemic

Guidry’s research is contributing to communication amid COVID-19. But an underpinning of much of her work, she says, is applying lessons from the current pandemic to the next one.

Much of the response to COVID-19 was predictable based on past outbreaks, Guidry said. It was no surprise, for example, that misinformation continues to flourish online. It was no surprise that vaccine hesitancy continues to increase.

Guidry hopes her research will help health officials more effectively communicate to the public when the next pandemic arrives.

“The World Health Organization said recently that they don’t necessarily think this was the big one, that COVID wasn’t the big pandemic,” she said. “If this is not the big one, then I want us to be ready whenever it does show up.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.