March 2, 2022

From refugee to Ph.D.

Share this story

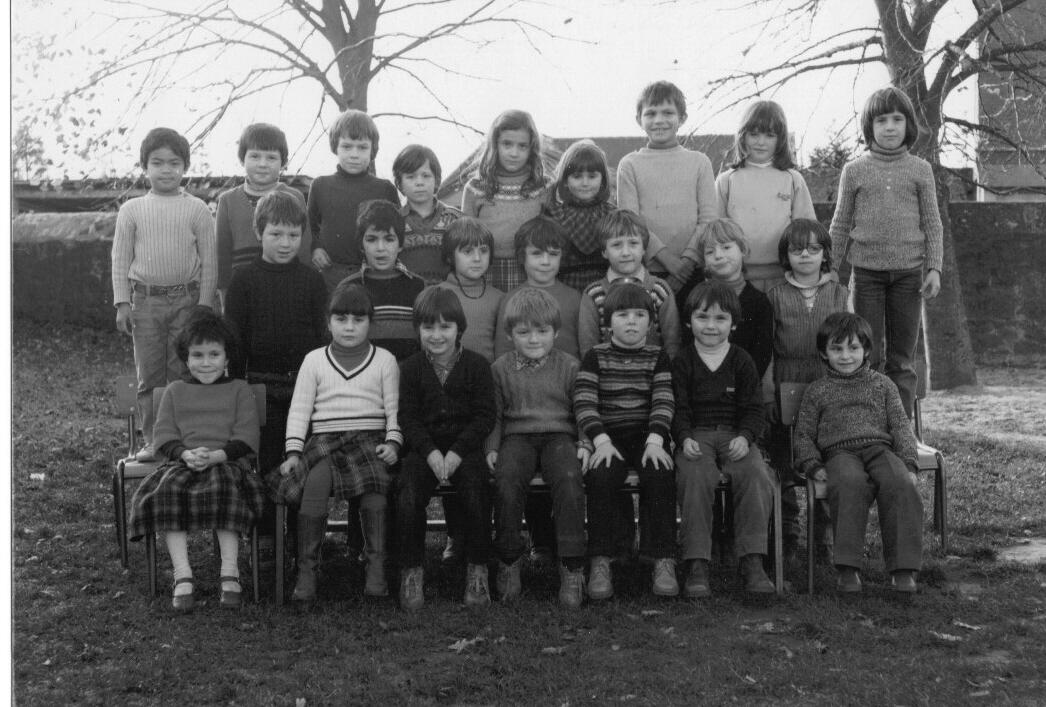

Nathan Tuoch has come a long way since he first stepped into a classroom. As a young Cambodian refugee who resettled in France with his parents in the 1970s, he initially found school to be an overwhelming, boring and entirely foreign experience. He recalled sitting in the back row, his mind wandering, unable to focus on the teacher’s rapid French.

“I don’t know how my learning began,” he said. “But just like any kid, I adapted to the language and got used to it. It was strange, but at the same time it was very cool.”

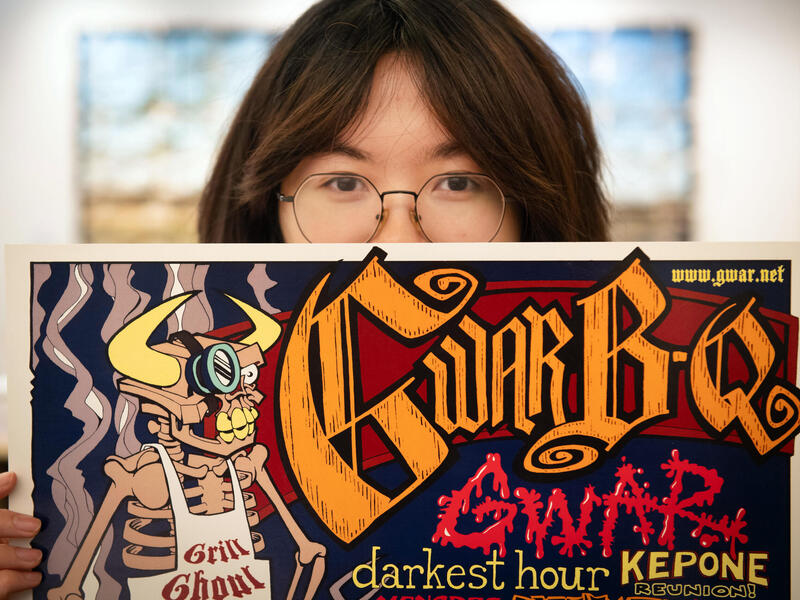

Now a first-year Ph.D. student in the Department of Radiation Oncology’s rigorous medical physics Ph.D. program at Virginia Commonwealth University’s School of Medicine, Tuoch feels at home in the classroom. He already has a bachelor’s and two master’s degrees under his belt, and with another doctorate degree — a D.Sc. in health sciences at Drexel University — also in the works, he prides himself on being a lifelong learner.

“I want to be a student forever,” he said on the day of his graduate program orientation, the corners of his eyes crinkling as he smiled and gazed around the lobby of McGlothlin Medical Education Center on the MCV Campus. “Knowledge is golden. I think everybody needs to acquire more knowledge, and it motivates me every day to move forward.”

This relentless pursuit of knowledge has been one of the few constants throughout a lifetime of extreme changes and challenges. And for Tuoch, the goal is not to add more letters behind his name — it is to obtain knowledge and use it to help others.

A story of survival

The youngest of 13 children born in Cambodia, Tuoch was a toddler when the Khmer Rouge, or the Communist Party of Kampuchea, began its brutal occupation of the country in 1975. Because Tuoch’s father was a high-ranking Cambodian military officer, he was targeted for fighting alongside the U.S. military during the Vietnam War, and the family was forced to flee.

In an attempt to keep his family safe, Tuoch’s father traveled solo along the coast, toward Thailand, to evade capture and torture. The rest of the family trekked a circuitous route of more than 200 miles from the city of Phnom-Penh through thick, unforgiving jungles to a refugee camp at the border of Thailand and Cambodia’s Pailin Province.

Tuoch and his mother were the only ones to make it out of the jungle alive. And by the time they crossed the border, Tuoch was barely hanging on, severely malnourished and ill with malaria. The pair prayed that his father would make it too.

Tuoch’s own memories of the journey are sparse, but many that remain are vivid, such as witnessing a fellow refugee lose his toes while pushing a makeshift cart through a river and peeling leeches off his own frail body after crossing a swamp. Some scenes, such as pulling his sister’s hair while she carried him, replay in a hazy corner of his mind, a space where pieces of his past are cobbled together with his own recollections and the projection of retold stories. He vaguely remembers his sister’s face, but not much else about her, his other siblings or what it was like to lose them.

“I don’t feel like I miss them because I think I never got to be emotionally attached. I was too young,” he said. People tell him he is lucky to not remember that pain, but he disagrees. “I wish I could because that’s how you build your wisdom — by going through those experiences. It opens your eyes to more things.”

His mom remembered, but she didn’t talk about it much — only when he asked. Tuoch believes it was the only way she knew how to cope with what she went through, while also protecting him. When his parents miraculously reunited in France years later and had Tuoch’s younger brother, they resolved to move forward, even if that meant not always being together. When Tuoch was in high school, his mother brought him and his brother to the U.S. while his father remained in France. During that tumultuous transition, his brother’s teacher took the two boys under her wing. Tuoch still keeps in touch with his “adopted American mom.”

His parents’ resilience and determination to pursue better opportunities for the family have been the driving forces behind everything Tuoch does.

“My only way of life is based on my parents’ experiences, strength and survival,” he said, reflecting on the unimaginable pain of losing 12 children. “Every day, I try to remember that nothing can be more difficult than what my parents went through.”

Finding his way

Tuoch has built a successful military career, but that was not the plan. Always drawn to medicine and science, he wanted to become a neurosurgeon.

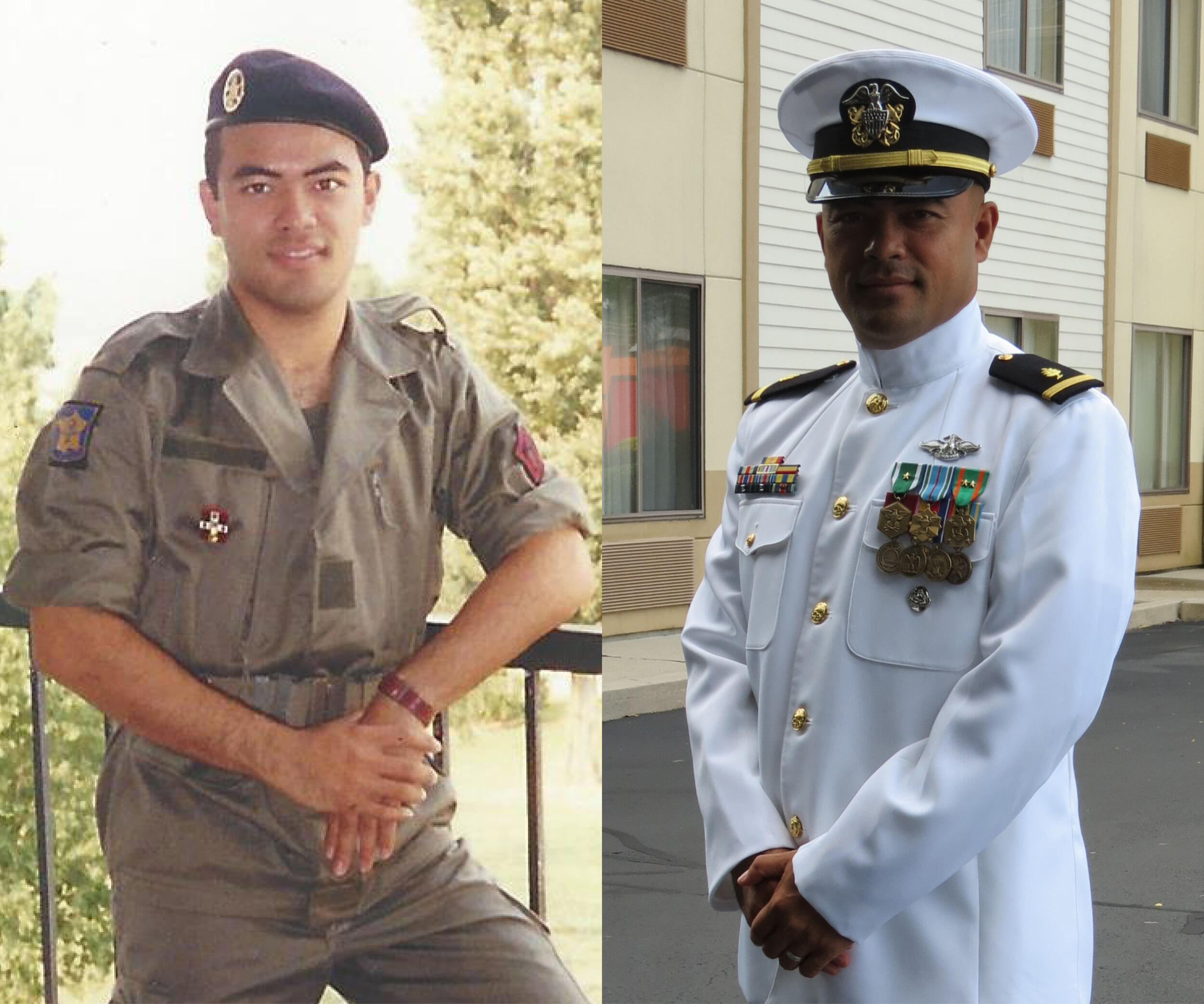

After graduating from high school, what he described as a mistake in the immigration process sent him back to France to straighten out his visa. But instead of processing his paperwork and returning to California, he was greeted at the airport with a letter from the French government instructing him to report immediately to a military base for two years of mandatory national service.

Deployed under NATO, Tuoch was sent to the Alps and the Macedonian mountains during the tense conflict that led to the Kosovo War in the late 1990s. The scenes of destruction and desperation against the calm backdrop of lush, green mountains felt all too familiar. It was another exercise in survival, and the experience stuck with him.

After leaving France, he returned to the U.S., where he attended Loyola Marymount University for a few semesters, his sights still set on medical school. But limited options as an undocumented immigrant meant working low-paying, under-the-table farm and factory jobs, which took its toll. His grades suffered, and he could no longer afford to stay in school.

Eventually, he went back to what he knew and enlisted in the U.S. Navy, where he worked as a special operations hospital corpsman. He later was commissioned as a naval officer and pursued radiation health physics, managing the radiation health and safety program on nuclear-powered carriers and submarines and at shipyards. Additionally, he was assigned to the Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute, where he began teaching and conducting research on radiobiology and the management of radiological casualties. Currently stationed at the Naval Dosimetry Center in Bethesda, Maryland, he leads the operations department. Now nearing retirement after 23 years in the Navy, he is eager to become a full-time student again, commuting to Richmond from his home in Northern Virginia for the medical physics Ph.D. program.

Tuoch said he has always enjoyed the scientific elements of his work, but he wants to do something with a more direct impact in health care. After years of searching for the right opportunity, he landed at VCU.

“I try to focus on my passion for what I want to do: healing people and helping people,” he said.

A desire to give back

At VCU, Tuoch is studying machine learning in Magnetic Resonance Imaging Guided Linear Accelerators in the hope of incorporating artificial intelligence into radiation treatment and improving quality assurance.

“One of the things I’ve always been passionate about is the passing on of knowledge,” Tuoch said. “Everyone has their own unique background, everyone has their own educational path, and there is always someone who will be enlightened or so happy to learn about it, and that’s what I want to do – teach and research.”

Meanwhile, he’s also about a year into his other doctoral degree at Drexel University, where he’s researching how to incorporate advanced modeling tools to treat radiation injuries in nursing and other health care professions. His wife, whom he describes as unwaveringly supportive, occasionally teases him, asking why he insists on returning to school over and over. For him, the answer is simple: He wants to give back.

“We’ve been helped since 1978, through the war, in the refugee camp. France adopted us as refugees, then I came to the U.S., and I have my adopted American mom here,” he said. “I’ve always thought I owe something, to be able to make an impact on other people. I haven’t made an impact on other people’s lives yet, and that is how I keep motivating myself.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.