Feb. 2, 2026

How AI is changing fashion

Share this story

Fashion might seem like a uniquely human pursuit — from the eye for design to the feel of material — but artificial intelligence is weaving itself into the realm.

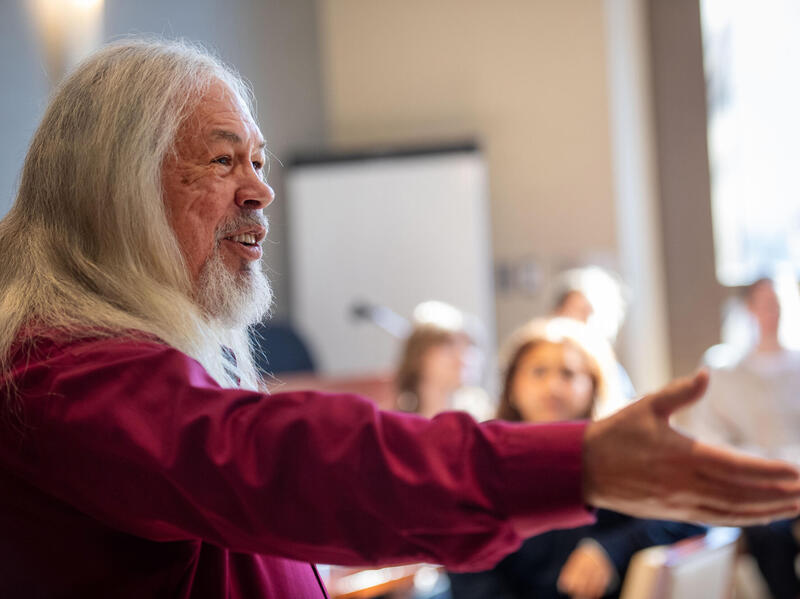

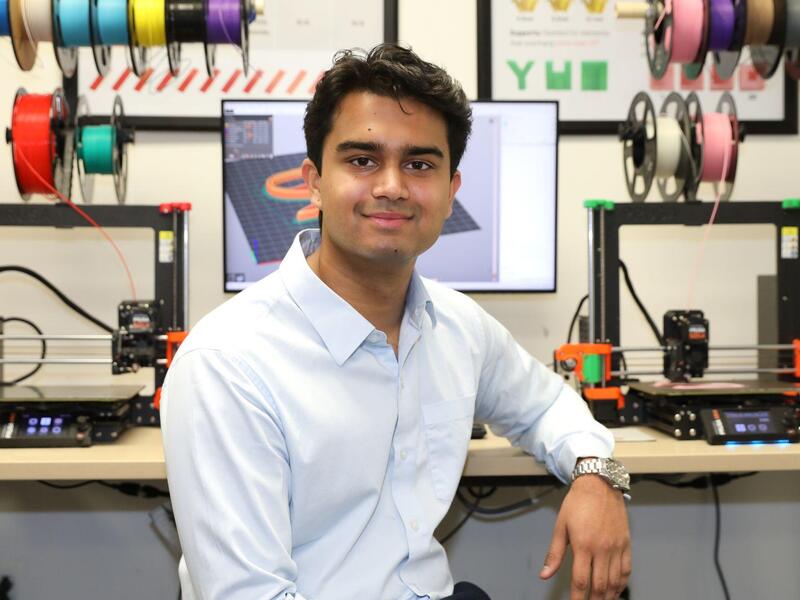

In Virginia Commonwealth University’s School of the Arts, Hawa Stwodah is an assistant professor of fashion design, and Jennie Cook is an assistant professor of fashion merchandising. Both have been exploring how AI is reshaping fashion, including in education.

VCU News asked them to stitch together some notable thoughts about the evolution.

Hawa, as a designer as well as an educator, give us a quick sense of how AI is impacting fashion design — and how you teach the discipline itself?

AI has impacted everything. Like others, the fashion industry has been integrating AI in various forms for some time. For the most part, it has been used to accelerate research and development and streamline production. Both the creative and business sides of the industry want to improve efficiency.

From an educational perspective, I always want to equip students and young designers with tools that help them expand their creative potential.

Jennie, what are the broad strokes of AI’s emergence in fashion merchandising?

AI didn’t emerge all at once in fashion merchandising. First, AI was implemented behind the scenes as infrastructure for merchandising decision-making. Long before students were prompting chatbots, brands were using machine learning to improve demand forecasting, size/fit predictions, allocation, dynamic pricing and product recommendations.

The second wave was the expansion of AI into consumer-facing experience and marketing systems. Personalization became the default expectation – i.e. what you see, what you’re served and what you’re nudged toward.

The third wave, the wave that most consumers could really “see,” was generative AI, which moved from analytics into creation: imagery, copy, concept boards, styling and early-stage ideation. It changed not just how work gets produced but how we define originality, skill and credibility in professional portfolios.

And now I think we’re in a fourth wave, where we’re seeing impacts to humans, and it’s leading to a socio-technical shift. The questions in merchandising aren’t only “Can we use it?” but “What does it optimize for?” and “At what cost?”

Hawa, what do you consider the biggest risks of AI in fashion design — but also, what might be its biggest reward?

Ethical and environmental issues come to mind as risks. I believe originality and authenticity can be compromised if the designer lacks a unique vision or voice.

The reward lies in rethinking consumption, waste, production and the core flaws of the system, which have exhausted resources and exploited communities.

Jennie, from your industry experience and your studies — including your master’s degree in product innovation from VCU’s da Vinci Center — what lessons from fashion and/or business provide good context for assessing AI’s emergence?

A lesson I carry from both industry and the da Vinci Center is that innovation rarely shows up as a single “genius idea.” It’s almost always ideation plus disciplined iteration – i.e. a cycle of generating possibilities, testing them against constraints and refining until something genuinely new and viable emerges. That’s a really useful lens for assessing AI right now, because AI is excellent at accelerating the front end of innovation: volume, variation, recombination. The risk is confusing more options with better ideas.

From a business of fashion perspective, competitive advantages usually come from what’s hard to copy: taste, curation and relationships. AI makes generic outputs easier to produce, which means differentiation shifts even more toward the things that aren’t easily automated – like a distinct brand identity, deep customer empathy and iterative refinement against real constraints.

I do not see AI as a shortcut but as a catalyst, a tool that helps us explore more territory early so we can spend our human time doing what innovations require — judgment, discernment and iteration — all of which can move something from “interesting” to truly distinct.

For both of you: Are you starting to see trends among your students in how they use or misuse — or understand or misunderstand — AI in the fashion space?

Hawa: Students in my design courses are very wary of generative AI. Initially, they are concerned about authorship, future career prospects, environmental ramifications and the value of creativity and talent. But after our class discussions and conversations weighing the benefits against perceived dangers, there is a shift toward a more nuanced understanding of how AI can be leveraged responsibly in the design process.

Jennie: Two big (and somewhat contradictory) trends are showing up at the same time.

First, according to a Google survey we conducted and our own lived experiences in the classroom, students almost universally don’t “like” AI, but a large percentage are using it anyway. They voice a real distaste for AI because it can feel like the opposite of what they value in fashion: authorship, craft, originality and the human story behind making. At the same time, they’re increasingly using AI.

Second, they have strong environmental concerns and fear being accused of AI hypocrisy. Fashion students tend to have a sophisticated understanding of sustainability (supply chain complexity, overproduction, waste, energy use), so they’re quick to connect AI to environmental harm — especially data center energy use and the broader “more tech = more consumption” pattern.

In terms of misunderstandings, some students collapse the entire conversation into “AI is always bad for the environment,” without distinguishing between low- and high-impact uses (e.g., light text help vs. heavy image/video generation at scale). And many don’t understand that even if they’re not using ChatGPT, they are still passively using AI in many ways throughout the day.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.