Feb. 12, 2019

International sex tourism is a booming industry. It’s also been happening since the 18th century.

Share this story

Alongside the rise of globalization has been an increasing growth of international tourism for the purpose of “exotic” sex.

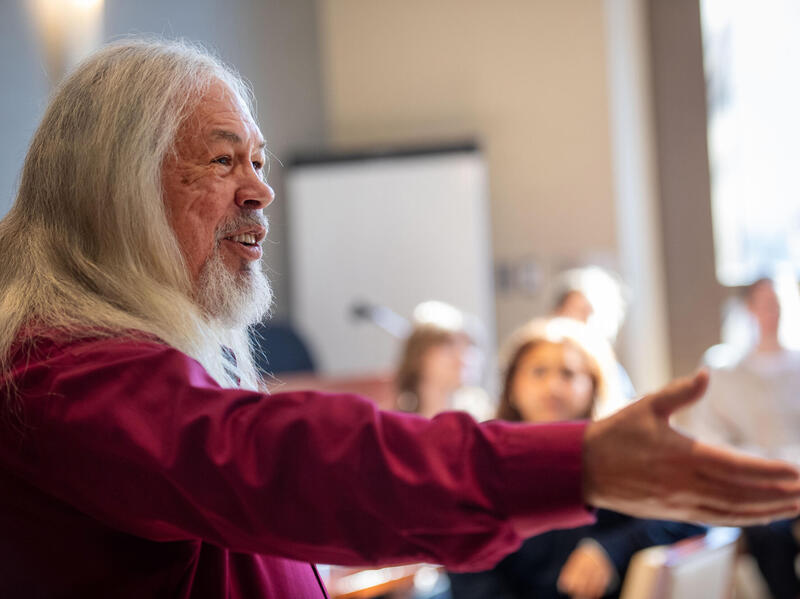

International sex tourism has become a booming industry, but it is not a new phenomenon. A new course taught by Christopher Ewing, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of History in the College of Humanities and Sciences, explores the history of international sex tourism from the second half of the 18th century — when European powers dramatically expanded colonization efforts in the Eastern Hemisphere — up to the modern era.

Ewing, an expert on LGBTQ+ history and modern European history, recently discussed his course in an interview with VCU News. International Sex Tourism 1750-Present investigates how travel has provided a means for middle- and upper-class Europeans and North Americans to realize sexual fantasies that hinge on the racialization and exoticization of people in the Global South, while simultaneously generating new forms of labor migration as populations move in pursuit of sex and work.

What led you to teach the history of international sex tourism and what is the course’s objective?

What I wanted to do with this course is bring my own research — which looks at West German gay sex tourism after the Second World War — into conversation with other trends in international sex tourism that have a lot to do with colonialism.

That’s why we start around 1750, specifically in 1763, after the end of the Seven Years War, [when] we begin to see a shift in focus in western European colonialism from the Western Hemisphere toward the Eastern Hemisphere, specifically looking at the French occupation of Algeria beginning in 1830 and the English occupation and entrenchment in India.

What I wanted to do is look at: OK, how does colonialism structure sexual desire? How does colonialism structure travel in pursuit of sex abroad? And build from there, using colonialism as a framework to look at these international trends in racialized sexual desire that continue today.

Because we’re still living with the legacies of colonialism and how people think about sex, both within Western Europe and abroad.

What overarching themes do you see with respect to the history of international sex tourism?

One theme that comes up both in my research and in this class is orientalism and how it’s both remarkably durable and incredibly malleable because you can’t pin it down to [the idea that] all Western Europeans thought about people of color, particularly people from North Africa, the Middle East and South Asia, in one particular way over time.

But what they did do is bring that knowledge of what they categorize to be the “Orient” into conversation with their sexual desires. Thinking about, OK, what we know about the so-called Orient at a particular moment in time is going to inflect desires in many different ways. And so, at least in my research, what you see is a weird shift, where in the ’50s and ’60s West German gay men are going to North Africa, drawing on those old ideas of so-called Arabic sexual perversity and being like, “Oh wow, there are so many opportunities for homosexual contact here because of that.” Now, at least in Western Europe, you see the opposite where Islam specifically as linked to racial conceptions of Middle Eastern and North African people is seen as antithetical to homosexuality.

Both are linked to Orientalism. Both are linked to a certain knowledge of this vague geographical area. But it can take on different forms at different times depending on who you’re talking to.

What do you hope the students get out of this class?

I want them to take an approach to contemporary issues around sex tourism that are historically rooted and also complex: On the one hand, we have to think about exploitation that goes on. On the other hand, we have to allow room for agency of people of color, sex workers abroad or people engaged in other forms of transactional sex or people who aren’t engaged in transactional sex but are sleeping with people that we might call sex tourists.

So taking both and thinking about: What are ways in which we can talk about exploitation while allowing room for agency and not being moralizing about sexuality? And how do we think about that as connected to the past

What are some ways in which international sex tourism has changed during the period you’re looking at? What are some of the ways it has evolved?

You have a couple of things that are conceptual shifts and also material shifts.

When we’re looking conceptually, you definitely see a change from the way in which travelers during the Enlightenment conceived of where they were going. They had this idea of, “Let’s go out and let’s categorize things.” Part of that categorization is also, “Let’s go have sex.” That kind of undermines it, but also supports it.

Around the Romantic period at the turn of the 19th century, you have a new understanding that going abroad is going to be something that’s transformative. That continues into what we might call the Victorian period, but that then comes into conjunction with an idea that Northern Europe is urbanized and gross and industrial and everywhere else is fun and sexy and clean, but also falling apart in weird ways.

By the 20th century you have major shifts in terms of thinking about race, where scientific racism comes into play, social Darwinism and eugenic thinking — that’s the idea of Western Europeans as being scientifically racially superior, but that doesn’t preclude possibilities for sex abroad.

And then just jumping through into the post-[WWII] period with decolonization. You have new ways of thinking about that, where leftist activists are starting to make the claim that going abroad and sleeping with anti-colonial revolutionaries constitutes anti-racist anti-colonialism, when in fact, it’s linked to this longer history of colonialism and it’s always going to be racially tinged.

You have this long timeline of large conceptual shifts that go back to this underlying current of Orientalism. At the same time, gradually over time, sex tourism becomes increasingly more accessible to people.

With technological innovations in the 19th century, with the advent of steam ships, things like that, it becomes easier to travel. In the 20th century, particularly by the 1960s and 1970s, jet travel becomes really easy. So that also changes where people are going.

In the Enlightenment era, it was all about the “grand tour” — going across Europe to Italy and Greece. That still exists today. I talk to my German friends, not necessarily about sex tourism, but they love Italy, they love Greece. They’ll still go there. But at the same time, now Southeast Asia is more accessible than it ever would have been in the 18th, 19th or early 20th century.

At the same time, with the emergence of European colonialism in these places, these also open up new spaces for sex tourists that weren’t necessarily accessible prior to European colonization.

So you see shifts happening in that material way where it’s like: OK, what becomes more accessible at a different movement because of geopolitics and technology?

What does sexual tourism look like today? And how has it been influenced by the history you’re describing?

Today you still have an ongoing trend of people with money — not necessarily even from Western Europe or North America, but East Asian countries and [Persian] Gulf states — who will go abroad in pursuit of transactional sex. At the same time, because tourism is so easily accessible to middle- and upper-class people around the world, you have people who will go abroad to tour and then use sexuality and sexual encounters as a way of exploring a new place.

You might have sex tourism [in which] students from the United States go to Southeast Asia and want to get access to the culture and then find locals to sleep with or build relationships with or fall in love with. Those are also forms of sex tourism, if we take a very broad definition.

Really it’s just any form of tourism that you can imagine where sexuality comes into play, where there is sexual contact. I encourage my students to think broadly about what sex tourism could be, because we have the conception that sex tourism is Western European and North American white men going abroad in pursuit of transactional sex with women of color. That does happen and we have to talk about that and we have to think about that, but at the same time, that happens alongside all these other different forms of travel and sex together.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.