Aug. 17, 2017

What is the psychology behind violence and aggression? A new VCU lab aims to find out

Share this story

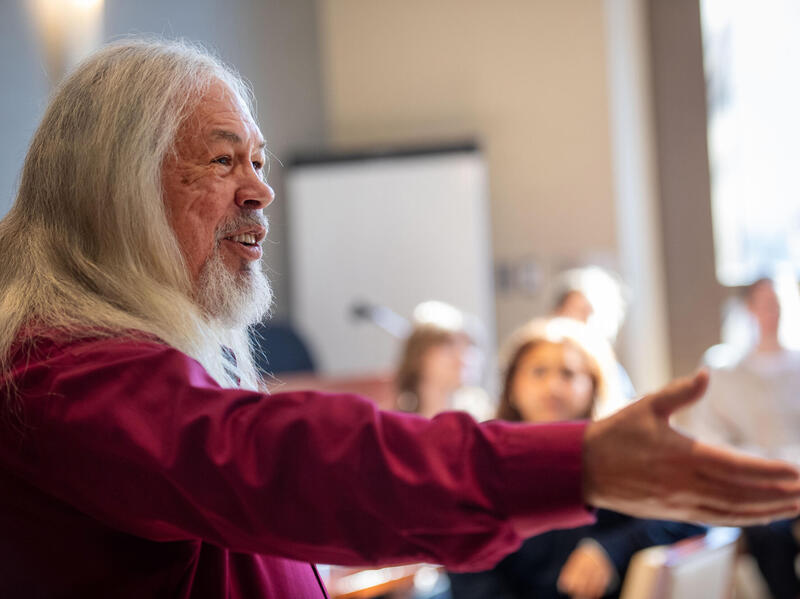

For his entire life, David Chester, Ph.D., has been driven by a single question: Why do people seek to harm others?

“As a kid, I’d see these news articles and local TV news showing murders and assaults and things like that,” said Chester, an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology in the College of Humanities and Sciences. “It always perplexed me because we’d done such a great job of moving forward as a species and building this great society, but we still kept one part of our prehistoric past — we kept this tendency to be violent and aggressive.”

Chester, a leading scholar in aggression research, is a recent addition to VCU’s faculty. His Social Psychology and Neuroscience Lab is launching a series of studies this fall that aim to further our understanding of violent behavior, exploring the role of the brain and human psychology behind topics such as revenge, domestic abuse, psychopaths, and much more.

“The goal of our lab is to reduce violence in the real world. That’s our mission statement. That’s what we’re here to do,” he said. “By laying bare these psychological and neurological processes behind aggression, we can gain some serious traction in how to go about doing that.”

Can violence be an addiction?

Chester’s recent research, in collaboration with Nathan DeWall, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Kentucky, has focused on whether violence might actually be addictive. And, if that’s true, could an addiction to aggression be treatable, similar to how alcoholism or opioid dependence is treated?

Conventionally, violence is understood to be often driven by negative emotions, such as anger or fear. For example, a person might become aggressive because they were enraged at another person, or they were afraid the other person might hurt them.

“Our lab has really shown that that’s true — negative emotions are there,” Chester said. “But positive emotions actually also play a pretty big role in aggressive behavior as well. So aggression can feel good. And that pleasure — and the associated, what we call hedonic reward — is a really potent motivating force.”

In other words, he said, aggressive behavior can be reinforced by positive feelings of power and dominance.

“So aggression isn’t just about ‘I’m angry and I want to hit someone,’” Chester said. “It’s also about how it feels good sometimes to get revenge on someone who has wronged you or who you perceive as having wronged you.”

That positive sensation, Chester has found, works on the same neural circuits as other addictive behaviors, such as cocaine, gambling and engaging in risky sexual behavior.

“It follows this trajectory where negative and positive emotion fit together,” he said. “So, ‘I feel bad, I don’t want to feel bad, so I’m looking for things that make me feel good.’ Well, we’ve always known that drugs and risky behavior are in that group. We’re saying that aggression belongs in that group too. And that people seek it out when they’re feeling bad. And that they use it like a tool to help themselves regulate their mood state. And when they do that, it activates these addiction circuits in the brain and it reinforces this behavior.”

In the months ahead, Chester’s lab is planning to launch a trial of a drug called Naltrexone to test whether aggression can be treated as an addiction.

“What [Naltrexone] basically does is it blocks pleasure,” he said. “It keeps you from feeling good from things that would normally make you feel good. It’s used commonly to treat alcohol dependence. These individuals, when they want to have a drink, they get a drink and they feel good. If you have a Naltrexone implant, which they replace every six weeks or so, you have a drink, you’re waiting for the buzz to kick in, you might get a little but you’re not really getting the same bump that you used to. Because this drug blocks the typical pleasure enhancing neurotransmitters and neurochemicals from doing their job. It stands in their way.”

So if aggression works on these same reward circuits, he said, it’s very possible that Naltrexone might also curb an addiction to violence.

“We’re looking forward to really testing this idea over the next year and see if we can’t leverage this idea and go out into the real world and maybe reduce aggressive behavior,” he said.

Understanding the psychopath’s brain

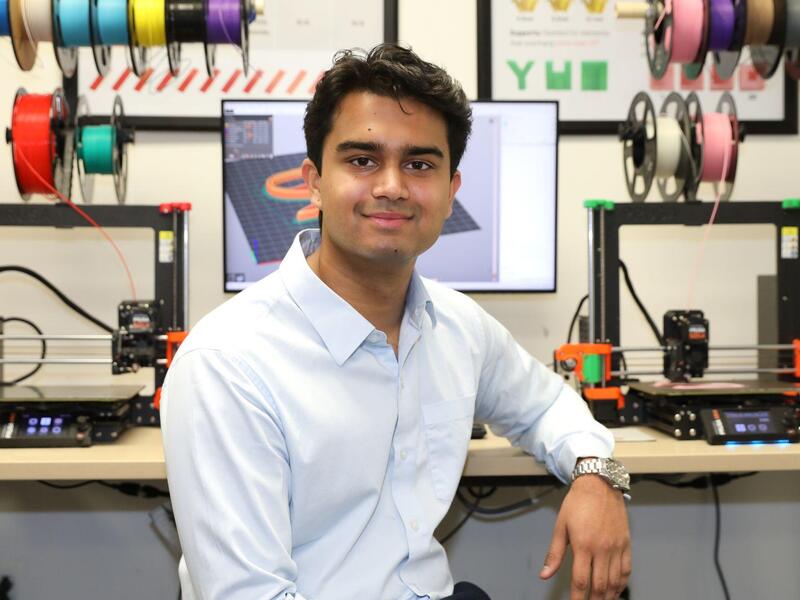

Emily Lasko is one of three doctoral students working in the Social Psychology and Neuroscience Lab. Her research focuses on the neurological connections between psychopathy, empathy and aggression.

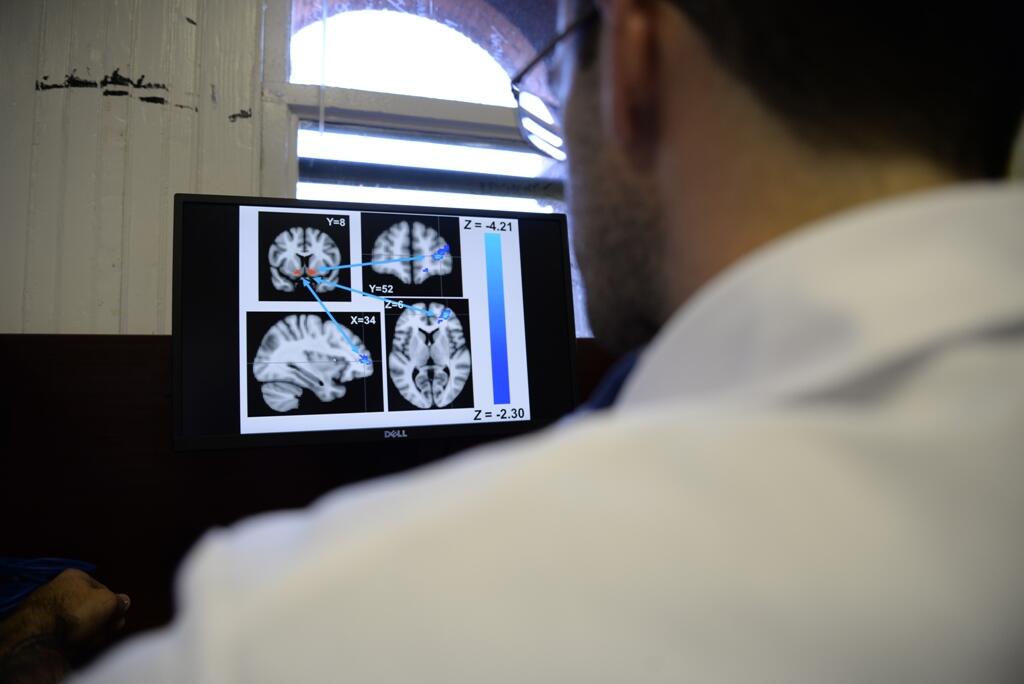

Specifically, Lasko has been investigating brain scans of people with psychopathic traits and finding that those traits may be related to gray matter density in regions of the brain involved in emotion processing and behavioral control.

“By gaining a deeper understanding of the biological markers of aggression, empathy and ‘dark’ personality traits, as well as understanding the ways in which such traits can emerge to be both maladaptive and potentially adaptive, we can be better equipped to develop early intervention strategies and rehabilitative programs for aggressive and antisocial behavior,” she said. “This knowledge will also facilitate efforts to target and foster potential strengths or adaptive features of the ‘darker’ personalities.”

Psychopaths are commonly understood to lack empathy, Chester said, but they frequently also have other traits, such as charisma and the ability to get what they want.

“There’s this notion of successful psychopaths, so think of like a CEO. Well, it’s not just that they’re walking around without empathy and that’s letting them get what they want. They also have these abilities to manipulate others. So that’s got to correspond to something in the brain,” Chester said.

“So we see that they have this increased gray matter density — and gray matter where information processing happens, that’s where the work gets done — in these parts of the brain called the lateral pre-frontal cortex, which is really involved in self-control, self-regulation.”

Lasko’s data suggests that psychopaths’ gray matter density may give them greater control over how they regulate themselves, allowing them to adapt to different situations more easily and to manipulate others.

Aggression and romance

Another doctoral student, Alexandra Martelli, is exploring intimate partner aggression and is currently running a study in which she observes the brain activity of couples who are actively acting aggressively toward one another.

“Close relationships are vital for our well-being and overall happiness and when we have unresolved conflict with close others it can have devastating intrapersonal consequences on our health and well-being,” Martelli said. “Especially in relationships where one or both partners suffers from various psychopathology — such as depression, anxiety, addiction or alcoholism — which can put additional stress on the relationship.”

Previous studies have looked at the consequences of intimate partner aggression and how that affects the brain. Martelli’s experiment is believed to be the first to involve watching that brain activity in real time, as the conflict is occurring.

“We’re really trying to explore what neural mechanisms, what brain processes are promoting and causing people to harm their romantic partners,” Chester said. “What we’re looking at is, that given that intimate partner aggression is kind of a unique flavor of aggression, it’s its own kind of thing. What is the brain doing to create that, as opposed to just being aggressive?”

Martelli’s research interests include mindfulness training and how that can help healthy relationships function.

“My main interests involve better understanding how mindfulness training can improve relationship functioning in distressed couples, as well as to better understand the neural mechanisms involved in mindfulness mediation and its impact on emotion regulation and relationship outcomes,” she said.

Why do some serve revenge cold?

Doctoral student Sam West is looking at provoked and unprovoked aggression in an inter-temporal context — meaning, people sometimes want to hurt someone immediately, whereas other times they might choose to wait a while in order to exact a greater revenge.

“We know like nothing about that,” Chester said. “We do not understand the motivational properties behind why some people choose to get aggressive sometimes right now in the moment versus why they’re sometimes willing to wait and exact revenge at a later time.”

West, who has conducted research on social rejection, aggressive behavior, disgust, and dehumanization, is developing a new research paradigm for examining aggressive behavior as a reward in the context of delayed gratification and socio-economic status.

He is adapting an experiment used in addiction research, in which people who are, say, cocaine dependent are offered an immediate bump of cocaine, or a greater amount if they wait a certain amount of time.

“The people who choose the immediate bump, that’s the trajectory you really don’t want to be on. These are the people who have the worst outcomes,” Chester said. “It’s this idea of rewards — you can have a small reward now, or a bigger reward later. And so we’re doing the same thing with aggression.”

West’s findings could hold implications for addressing violent crime.

“What we're seeing from very preliminary work is that it does appear to make a similar pattern of responding (e.g., most people prefer the immediate reward) when compared to simply receiving money,” West said. “A recent study we conducted indicated that perhaps self-control is the strongest predictor of this as a higher ability to pause before acting in order to inflict more damage in the future.”

Understanding aggression

In order to reduce violence, Chester says, we must first gain a deeper understanding of why people are violent.

“To use a metaphor, there’s a lot of mechanics who are working on a car, but they don’t know how the car works,” he said. “There’s thousands of people working to reduce violence every day, trying to make the world a less violet place, but we don’t know how it works, you know?”

“So what we’re doing in the lab is we’re studying the car,” he said. “We’re studying the brain and human psychology, trying to understand what motivates people to be aggressive. That way, we know where to look when we’re trying to fix the problem.”

Each issue of the VCU News newsletter includes a roundup of top headlines from the university’s central news source and a listing of highlighted upcoming events. The newsletter is distributed on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. To subscribe, visit newsletter.vcu.edu/. All VCU and VCU Health email account holders are automatically subscribed to the newsletter.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.