Nov. 18, 2025

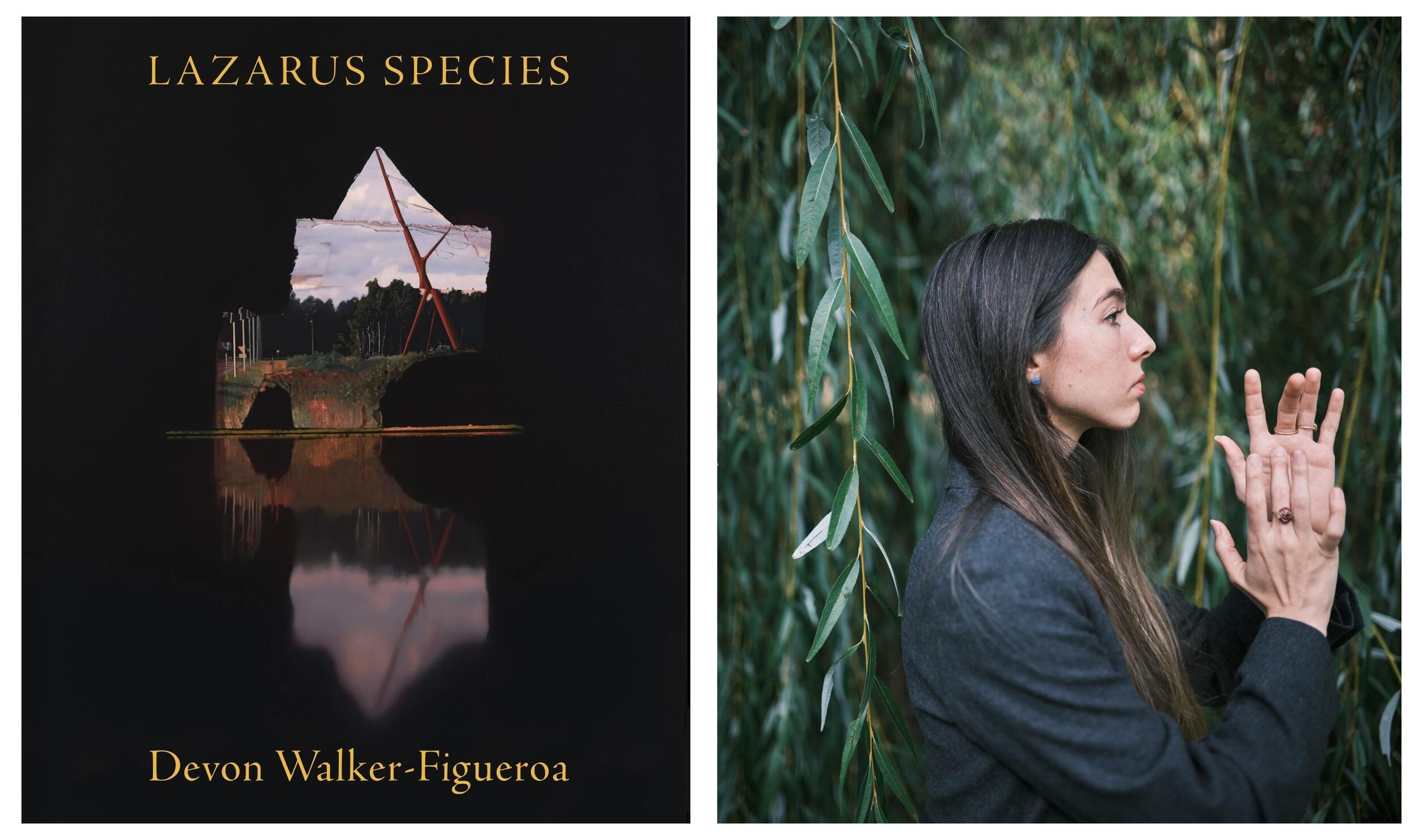

Devon Walker-Figueroa embraces the ‘odd bird’ that is ‘Lazarus Species,’ her new poetry collection

Share this story

In her second book, Devon Walker-Figueroa went to the roots of her most enduring fascinations and found a connective force among them: resurrection and the inextricability of endings and beginnings.

With her poetry collection “Lazarus Species,” Walker-Figueroa, an assistant professor in the Department of English in Virginia Commonwealth University’s College of Humanities and Sciences, explores themes that cover space and time. Her influences ranged from Sumerian and Babylonian myths to neuroscience, from historical figures to hydroelectric and aerospace technologies.

In the end, she said, “what arose from this wandering was a network of conversations, of calls and responses – all across time, space, language, culture and poetic form.”

Walker-Figueroa spoke with VCU News about her “odd bird of a book” and its meshwork of themes.

With such a broad array of influences, how did you pull everything together to create your unique vision?

I would say the sense of line, from poem to poem, keeps the sonic weave tight enough that I could take leaps and liberties in other areas, such as concern or location or even register. All to say, if the reader has something to hold on to – whether it’s music or a series of images, the thread of a meditation or even a mood or quality of voice – you can stray in other ways: They won’t get lost if they have that compass point, that pattern, to keep them with you and to offer them sufficient familiarity that they might feel poised for the task of reckoning with novelty or a swerve in attention.

Many of these poems were initially drafted in classical forms but took on a new life through revisions. Why?

Classical forms have always attracted me. I have a background in classical harp and ballet, and formal rigors, far from feeling restrictive to me, feel like permission to deeply inhabit a technique and then meaningfully transform and disobey it.

In this collection you’ll find an assortment of forms, including ghazals, sonnet crowns, sestinas, villanelles, a pantoum, some husks of englynion and even a few that I sort of just came up with on my own.

As I wrote into these strict patterns, I wanted to see how they warped under the weight of modern anxieties.

Modern anxieties? Tell us more.

For example, in a moment with such a fraught and relative and technologically mediated relationship to history, why not have the villanelle mis-remember its own refrain? So the line “repeats,” but it really only sounds as if it repeats – through metrical and consonantal mimicry – while something, such as the words themselves, has been changed.

In another example, during the height of the pandemic, I wrote a crown – or corona – of sonnets and thought, “Why not allow the form to be incomplete?” In the sense that it’s not activated or proliferative without a host, RNA is incomplete, just like the poem is incomplete without a reader, or in the context of the poem’s subject, the speaker is incomplete without the beloved who has fallen gravely ill with COVID-19. With all this in mind, I strategically corroded the crown form down, collapsing it to a fraction of its former full-length self so that it sits dormant until someone picks it up and reads it, allowing it to be “transmitted.”

Additionally, many of the ghazals practice a great deal of fidelity to the original form; however, they all have a lot of caesurae, or intra-line spaces, breaking up the flow of the discrete and normally orderly couplets. They end up feeling shattered, scattered, decoupled – which, while not my initial goal, seems an apt result in such a fragmented, if not neo-futurist, moment as our own.

Among those forms you came up with is what you call the ‘polyphase sestet.’ What inspired you?

When I was studying Nikola Tesla’s patents for the rotating magnetic field dynamo (or induction motor), I thought, “Oh, this point falls nil right as its counterpoint takes over the charge – I can use this to alternate between points of view between Nikola and his older brother, Dane,” who tragically died in an equestrian accident at the age of 12.

In essence, a rather mechanical and predetermined motion back and forth becomes charged as it crosses the threshold between the brothers’ consciousnesses but also the threshold between life and death, activation and nullity.

How does this new collection – and your recent novella, “Hold Harmless” – build on your previous work?

Since I began working on “Lazarus Species” at the same time as I began work on my first book, “Philomath,” I can’t say that one follows from the other. But I do think that the two books share a common fascination with abandoned places, with history and with the huge distances – emotional, generational, spatial, ideological, technological and more – that we as sentient beings are constantly traversing in order to reach one another.

“Hold Harmless,” released in October in the new issue of Ploughshares, specifically deals with found family and how individuals who have divergent and even competing drives can come together to create, however briefly and even perilously, a sense of belonging in a world that is increasingly hostile to human interconnectivity.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.