May 30, 2018

Since Ancient Greece doctors have relied on patients to tell them what medications they are taking. They may no longer need to.

Share this story

Every day, in thousands of emergency rooms around the world, doctors face a daunting mystery: What medications are in a patient’s body?

That question can be one of life or death, and since the days of Hippocrates doctors have relied on the same method for answers: They ask the patient.

Now, thanks to collaborative research at Virginia Commonwealth University, they may soon have a much better option.

The presence of drugs such as blood thinners or heart medications can dramatically affect the way a patient reacts to wounds or medical treatment. Unplanned withdrawal from medication can lead to medical crises in patients who are hospitalized. Drugs used in emergencies could interact badly with those that are already in a patient’s system.

“In emergencies, we have to depend on the patients or their families to tell us what they are taking,” said Sudha Jayaraman, M.D., a VCU Health surgeon who specializes in trauma and other emergency cases.

There are major drawbacks with that approach, particularly in emergencies. Patients may be unconscious or incoherent or simply unsure. Family members may not know what medicines have been prescribed, much less taken. The patients’ doctors and pharmacists may be hard to reach on short notice.

And while paramedics transporting patients to the hospital are trained to “grab all the meds and bring them in a bag,” Jayaraman said, that information is of limited use if there is no way to know which of those drugs might be in a patient’s system.

A national problem

More than half of hospitalized patients have at least one unintended drug interaction while under medical care, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Of the unintended interactions, 39 percent had potential for severe or moderate harm.

“Those kind of things happen all the time,” said Gretchen M. Brophy, Pharm.D., professor of pharmacotherapy and outcomes science and neurosurgery at the VCU School of Pharmacy. Brophy is also a practicing neurocritical care clinical pharmacist at VCU Health and president of the national Neurocritical Care Society.

She offered an example: “A patient might go into a seizure in the emergency department and no one knows why,” Brophy said. “It turns out he is supposed to be on anticonvulsant or anti-epilepsy drugs, but he no longer has the medication in his system.”

The process of ferreting out which medicines are affecting patient health is called medication reconciliation. It is an important part of health care in general. In emergencies, the mystery can rise to a crisis level.

Standard blood tests for medications can take up to two weeks to process. Emergency department physicians, sometimes making decisions in seconds, need answers quickly.

With more than 130 million emergency department visits a year in the U.S. — 12 million of them serious enough to warrant hospital admission, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — a lot of patients are potentially at risk for dangerous medication interactions.

A new approach

A few years ago, the situation got Jayaraman thinking. How can modern emergency medicine, with its wondrous technology, still be using the same medication-reconciliation techniques it has for centuries — even as drugs have become more common? It was like a modern crime-scene investigator forced to use 18th-century technology rather than current forensic science.

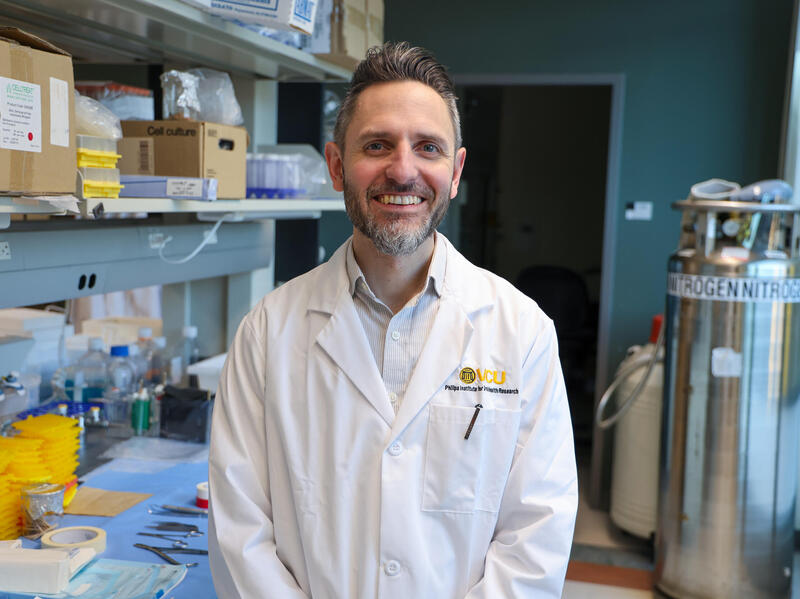

Jayaraman, an associate professor of surgery in the School of Medicine, mentioned the mystery to a colleague, Dayanjan “Shanaka” Wijesinghe, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Pharmacotherapy and Outcomes Science at the VCU School of Pharmacy.

Wijesinghe was intrigued: “Basically, the doctors are working blind when it comes to medications,” he said.

But Wijesinghe quickly connected the issue to a technology he knew well. “I told her, ‘We have been doing this in the lab for a long time,’” he recalled.

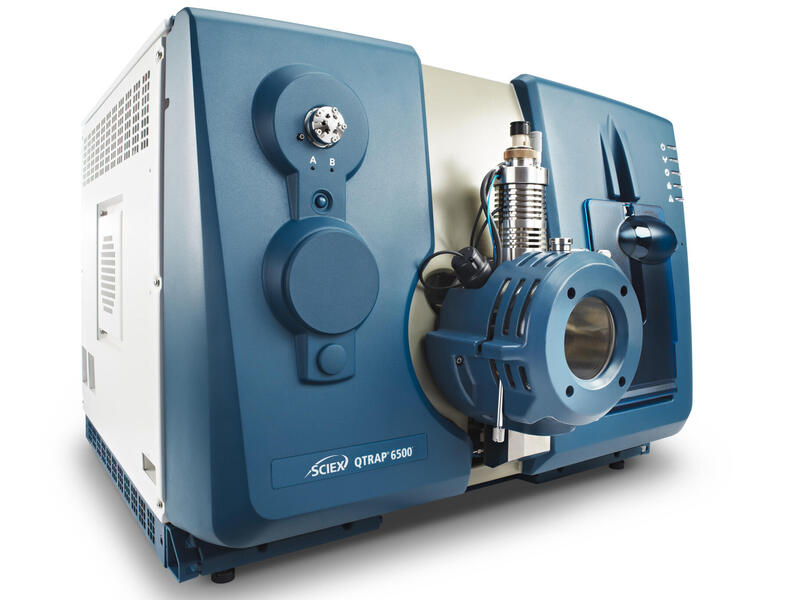

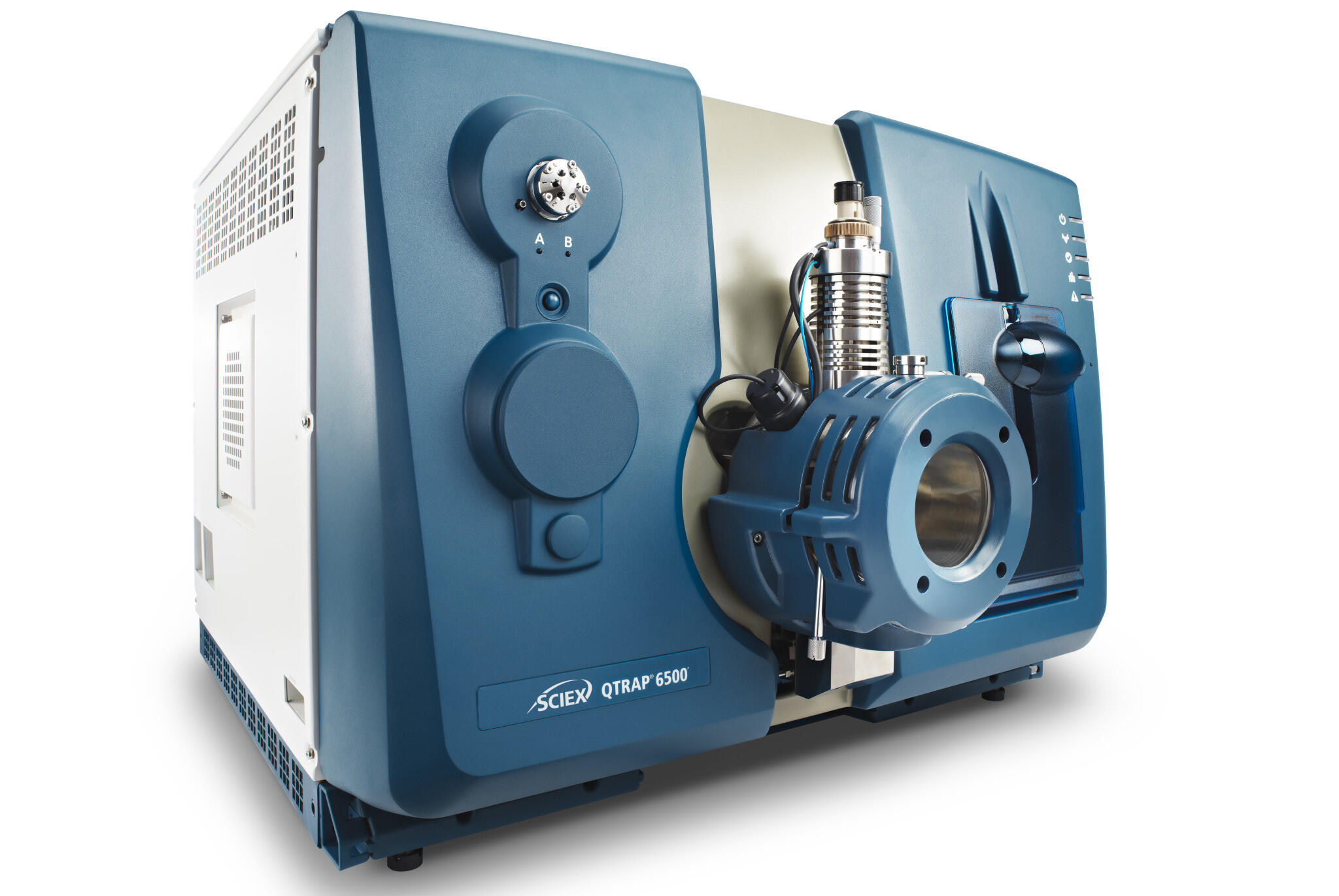

The technology was mass spectrometry.

Mass spectrometry is a term used to describe an umbrella of technologies that allow the identification of a molecule by measuring its mass and then breaking those molecules apart and also measuring the masses of the fragmented components. The information gleaned from the technology can be compared to a database of intact and fragmented component masses of known compounds of interest to find the identity of the mystery molecule.

With this approach in mind, Wijesinghe and Jayaraman obtained grants from VCU’s C. Kenneth and Dianne Wright Center for Clinical and Translational Research and the Commercialization Fund, which is intended to advance VCU inventions to a more mature stage and improve their chances of being brought to market. Their objective was to assess the feasibility of using mass spectrometry in a clinical setting. With support from VCU Innovation Gateway, they have applied for a patent on the application and set up a company to market it, Mass Diagnostix.

In this early phase, the project aims to catalog 50 common drugs; so far, they have molecular signatures for 45, Wijesinghe said.

The future of patient care?

The interdisciplinary VCU team hopes the use of mass spectrometry to analyze patients’ medications will become common practice. They predict in a few years, use of the machines — which cost about $500,000 — will be standard practice for hospital laboratories.

The next step will be to expand the catalog of molecular signatures to many more medications — at least 100, Jayaraman said.

Wijesinghe suggests other possible uses. For example, he said, these instruments could record subtle changes in patients’ metabolisms that could predict life-threatening health crises before they happen.

Jayaraman and Wijesinghe are among the co-authors of a recent paper in the medical journal Shock that examines the possibility that mass spectrometry, along with other tests, could reduce deaths from trauma and its ensuing complications. Almost 200,000 trauma-related deaths occur every year in the U.S., most as a result of complications arising after the injury itself.

If this expansion of the technology into diagnosing future problems proves fruitful — and the researchers caution that years of study remain before that is determined — the effort to solve the mystery of what medications hide inside a patient’s body could have major advantages.

“We are hoping that this test will improve patient care,” Jayaraman said.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.