Sept. 1, 2016

VCU social work students tour Richmond to explore ‘school-to-prison pipeline’

Share this story

Nearly 100 VCU School of Social Work students, faculty and staff members spent Wednesday engaging with Richmond community organizers, formerly incarcerated youth, Virginia policymakers and others about the school-to-prison pipeline that leads so many young people in the Richmond region — particularly African Americans — to end up in jail, or worse.

The students, part of the School of Social Work’s Black Lives Matter Student and Faculty Collective, were participating in the group’s second Richmond [Re]Visited event, in which they take a bus tour of Richmond and meet with community leaders to discuss and learn about the city’s history of segregation and discrimination, and to better understand the issues facing social workers and the community today.

This year, organizers decided to explore the impact and historical context of the school-to-prison pipeline, which refers to the policies and practices that push schoolchildren out of the classroom and into the criminal justice system.

“We want social work students to know that they have opportunities to work with children, families and adults at multiple points in the pipeline as well as be involved in advocacy and community organizing efforts aimed at dismantling the school-to-prison pipeline,” said Stephanie G. Odera, assistant professor in teaching at the School of Social Work.

As Richmond Re[Visited] got underway Wednesday morning, Odera told the students — which included social work undergraduates, master’s students and doctoral candidates — that the pipeline is a manifestation of systemic, institutional racism that disproportionately affects students of color, and particularly African Americans, and students with disabilities, through zero-tolerance policies that criminalize relatively minor misbehavior.

“The pipeline is a passion issue for me, not only because I’m a former Richmond City school social worker or that I’m raising a little black boy who will soon enter kindergarten, but also because I am a former truant,” Odera said. “I could have easily ended up further in the pipeline myself had it not been for protective factors that were present in my life.”

Virginia schools refer students to law enforcement agencies for misbehavior at a rate nearly three times the national average, making Virginia the No. 1 state in the country in terms of schools referring students to law enforcement, according to a 2015 analysis of U.S. Department of Education data by the Center for Public Integrity.

“The national rate was about 6 referrals for every 1,000 students. In Virginia, it was almost 16 referrals per 1,000 students,” she said. “Some of the individual schools in Virginia with the highest rates of referrals — [one was as high as] 228 students per 1,000 — were middle schools. We’re talking about 11- to 14-year-olds.”

African-American students, she added, accounted for 38.3 percent of Virginia students referred to law enforcement, though African Americans make up only 24 percent of the state’s student population.

“Thousands of Virginia students in one year were sent to the criminal justice system by school police, mostly on charges of disorderly conduct — which seems to have become a catch-all — assaults and resisting arrest,” she said. “So what kind of behavior are we talking about?”

A 4-year-old preschooler in Greene County was taken to the police station and shackled in handcuffs for throwing a temper tantrum, she said. A 14-year-old girl in Henrico County was suspended for more than a month and charged with assault and battery after throwing a baby carrot at a teacher. An 11-year-old with autism in Lynchburg left class without permission, and was handcuffed and arrested for disorderly conduct, as well as felony assault, when he struggled with police. A 14-year-old with depression and anxiety was locked in a seclusion room, and was charged with disorderly conduct and destruction of property after breaking a doorknob trying to get out, she said.

“Noticing similar trends in Georgia — which was 40th on the list of states that refer kids to law enforcement — a juvenile court judge asked: ‘Why is it that most of the kids referred to my courtroom are kids who make [adults] mad, not the kids who scare us?’” McClellan said. “Have we over-criminalized childhood?”

Eight bills dealing with school referrals to law enforcement were considered by the General Assembly this year, she said, and two passed.

One bill made it so that if a child with an IEP or mental or behavioral health disorder is arrested for disorderly conduct at school, the student may enter that as evidence to be considered by a jury. The second, which McClellan sponsored, took away a requirement that school resource officers had to enforce school codes of conduct.

“School resource officers are defined by the code as those who have to deal with truancy and school safety, but we have a grant program in the state that funds some of these officers that also says that as part of their job, they have to enforce school codes of conduct,” she said. “It is not a police officer’s job to decide if your skirt is too short. They don’t want to do it. And more often than not, with a kid who has a disability or who has other emotional challenges going on, it could lead to something else.”

Art by incarcerated youth

![The Richmond [Re]Visited group checked out art produced by incarcerated young people at ART 180.](/image/4264eae3-8812-4a50-ac31-27eb7d4fdabc)

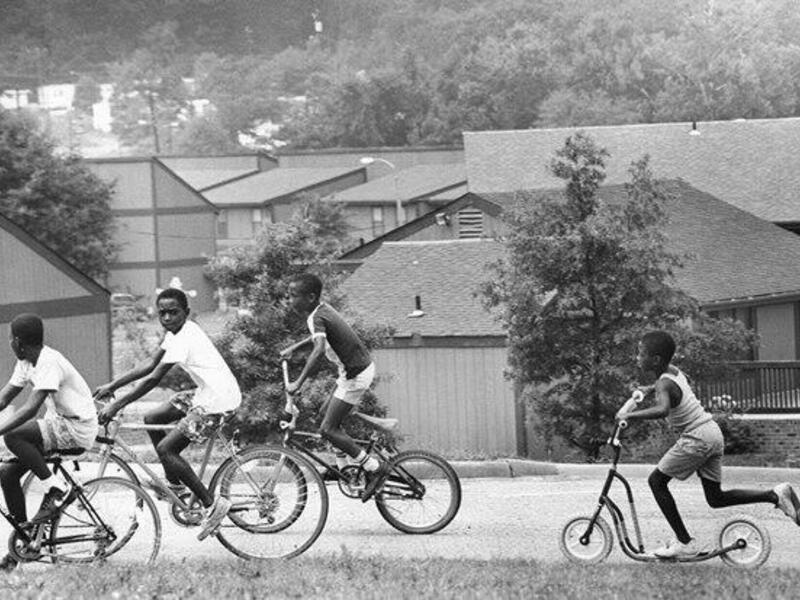

After McClellan’s talk, the students loaded onto two buses for a tour of Richmond, during which organizers pointed out and gave the history of public housing developments Gilpin Court and Mosby Court, the Richmond Justice Center, Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School, Richmond Alternative School, and the Richmond Juvenile and Domestic Relations District Court.

The group stopped by ART 180, a nonprofit that creates and provides art-related programs for young people living in challenging circumstances, encouraging personal and community change through self-expression.

Surrounded by art created by incarcerated young people, the VCU students heard about a project called Performing Statistics, in which youth incarcerated at the Richmond Juvenile Detention Center visit ART 180 to produce art that visualize their ideas for transforming the juvenile justice system.

Performing Statistics, a project of ART 180 in partnership with Legal Aid Justice Center, connects incarcerated teens with artists, designers, educators, and policy advocates to transform the juvenile justice system, and aims to empower them to become creative and civic leaders who can affect the laws and policies that affect the school-to-prison pipeline.

“We connect them with lawyers and artists and radio DJs and all kinds of people to talk about not only their own lives but also what their communities need and what our state needs — and we use art to amplify their voices,” said Mark Strandquist, co-director of Performing Statistics.

Marvin Brown, a 22-year-old from Richmond and an advocate with the Rise for Youth Network, told the VCU students how he worked with the incarcerated young people taking part in Performing Statistics, as well as his own experience with the criminal justice system.

“I was impacted by the justice system as a youth and an adult. As a youth, I did two months at James River Juvenile, and as an adult, altogether, I did like two-and-a-half years,” he said. “My first encounter in adult jail, I was 18 years old. I was incarcerated for unlawful entry and petty larceny. And I didn’t learn my lesson. The judge slapped my hand. I didn’t learn my lesson. So I came back in the next 10 months for a burglary and grand larceny.

“While I was in there, I transformed myself,” he said. “I realized this was not what I wanted in my life. God had given me a chance to make things right and help others. I don’t want anyone else to go through what I went through. I changed my way. I realized that my passion is giving back and speaking to the youth.”

The art produced this summer at ART 180, he said, gives a voice to incarcerated youth, and as well as an outlet to express what is going on in their lives.

“I feel as though if we were able to deal with our youth’s flaws and give them an outlet, we’d set them up for success,” he said. “Just because we made a mistake doesn’t mean that we have to be a statistic. Right now we are being judged every day. There’s a 73.4 percent reconviction rate. That means that within a span of three years, our youth are going back to [jail]. Prison doesn’t work.”

Understanding the past

The VCU students also visited Pilgrim Baptist Church, located in the historically African-American neighborhood of Whitcomb in the East End.

“If you’re going to be a social worker, you need to understand how the people you’re dealing with arrived at where they’re at,” he said. “It just didn’t happen overnight. And to be honest and specific, there was systemic, institutional and constitutional efforts to create the environment that the underserved live in.”

The church’s surrounding neighborhood, Turner said, was originally a blue collar, middle class community, with a high percentage of home ownership. In the 1950s, however, the city opened a dump across the street, causing property values to plummet.

“Homeownership is the first leg of wealth building,” he said. “Here we have a landfill placed in the heart of a stable, middle class community. Not only did it reduce the property value and the wealth of the community, it also created some ecological ills that produced societal ills.”

The city also opened a public housing development, introducing a variety of additional challenges.

“I’m a product of public housing myself,” Turner said. “But I also know the ills of public housing. When they brought public housing into the mix, not only did they further reduce the property value of the community, it also created additional social ills.”

Around the same time, Turner said, construction of the freeway displaced 10 percent of the city’s African American community and destroyed 50 percent to 60 percent of African American owned businesses.

“To go into communities as social workers, you have to understand what you are stepping into,” he said. “These ills were not just created yesterday. And, in many ways, they were intentional. They are systemic. What happened in the 50s, is [there was] a system that didn’t care about [this community] and imposed its will.”

Also at Pilgrim Baptist Church, Jamal Kelly, a counselor at the Richmond City Justice Center, told the VCU students that he considers himself a “key witness” to the school-to-prison pipeline, having worked for years as a counselor in East End schools and now in the city’s jail.

“We talk about the school-to-prison pipeline, which to my thinking is just a microcosm of a larger problem — deep-rooted racism,” he said. “I want to make sure that we understand that this didn’t happen overnight and it wasn’t circumstantial. I’m a firm believer that it was deliberate.”

During his first week at the jail, Kelly said, he was recognized by a countless number of former students from his schools.

“My director took me on a tour and so many residents, or inmates — we call them residents now — came up to me, saying ‘Mr. K, didn’t you used to work at my school?’ My director asked me, ‘Is there anybody in this building that you don’t know?’” he said. “I was happy to see that they were alive, but it disturbed me to see how comfortable they were [in jail]. Just smiling and happy and energetic. I had to take a step back and say, ‘This person has their freedom restricted. They live in a 5-by-9. They’re told when to eat, when they can go to the bathroom.’ There was a comfortableness that they had that disturbed me.”

When working with young people from neighborhoods like Whitcomb, he said, future social workers must try to understand the historical context of their experiences, and must also try to stay resilient in the face of adversity.

“You can’t take the backlash personally, because they’re going to lash out at you,” he said. “But once you show that you have some resilience, that you’re willing to work with them in spite of them calling you all sorts of names and threatening you, once you show some consistency, you’ll see how they start gravitating toward you.”

“The only thing I ask is that if you’re going to be in it, be in it for the long haul,” he said. “Because once they see that you’re not invested in them, it turns into depression, manifests into anger, and they start to turn to crime and it leads them into the pipeline.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.