Jan. 31, 2023

Is a return to the office inevitable? Should it be?

Share this story

Is it time to literally get back to work? Some major employers think so. COVID-19 has reached the endemic stage, meaning it is here to stay, and everyone is weighing how to live with the ebbs and flows of the virus. Against that backdrop, many major corporations are ready for employees to return to the office more often. Disney’s Bob Iger and Starbucks’ Howard Schultz are among numerous CEOs requiring their workers to spend a dedicated number of days per week in the workplace.

While this hybrid work week has become standard across the country, some companies are presenting it as a perk. KPMG calls it “Flex with Purpose.” General Motors Co. asks its employees to “Work Appropriately.” And 3M Co. asks its staff to “Work Your Way.”

Some employees are balking at the idea of changing out of their sweatpants or jeans and commuting to work. Others may not be as appeased by a “fun” new designation that means giving up the autonomy they have gained in recent years.

Has remote work been working? Are employers who are pushing for a return to the physical workplace trying to fix something that isn’t broken? VCU News turned to three business experts to explain what the “new normal” may look like.

Why are employers doing this now?

Susan M.T. Coombes, Ph.D., associate professor in the VCU Department of Management and Entrepreneurship: There can be a lot of reasons behind this. In many cases, organizations tend to want to revert back to “normalcy,” when given the first opportunity to do so. Even under typical circumstances, most organizations fight against changing in meaningful ways and will do so only when forced. When you have something in the environment that pushes organizations to significantly modify what they do, they’ll do that to survive. That’s what we saw with the pandemic – the need to physically distance and the consequent adaptation of people working from home.

If that force starts to subside? You’ll see a lot of organizations — a LOT of them — automatically take pains to revert to previous practices. It’s a matter of them thinking, “Oh, good, now we can get back to normal,” instead of assessing if that actually needs to be done or not. Remember, organizations are run by humans, and the majority of humans tend to like a sense of stability, even if it’s not necessarily the best choice for them — or their employees. In this case, that perception of “stability” is tied to a traditional measure that some employers still want to use: the eight-hour workday, five days a week, with people physically in their offices. Many employers want to “see” employees, to better trust that they are being productive. It’s not the most effective and efficient arrangement, in many cases, and employees themselves are realizing it’s an outmoded way to operate an organization.

Has there been any research — empirical or anecdotal — about how worker productivity fares in the office versus from home?

Coombes: If we look at the responses — either from personal experiences, or in general — you see a lot of push back from employees (even if it’s not always verbalized to employers). Given the option, there are many workers that would be more than happy to continue remote work, or very willing to convert to a hybrid arrangement (where they work from home at least a few days each week). Productive people don’t want to work remotely so that they can start ignoring their work responsibilities. Instead, they can be just as (if not more) productive, while also potentially developing an increased sense of well-being and work-life balance.

In reality, does productivity slide? Overall, the research says “no.” In fact, there is a lot of evidence that productivity generally increases when working remotely. As people have gotten used to working remotely, they’ve become more adept and efficient at it. In some cases, for better or worse, some employees might actually work longer hours from home (because, in essence, they never leave their “office”). At the same time, remote-workers may also have less traditional “stressors” — such as a daily commute, having to be “seen” toiling away in their offices, etc. — to worry about. While some workers may still prefer to work in the office, we should really start to consider remote and hybrid arrangements as long-term, viable options.

Where do you see remote work heading?

Coombes: Going back to the office, full-time, represents an unnecessary burden for many employees. We’ve seen the proof that working from home can be done, and it can be done well — in some cases, it can be done better. While employers have their reasons for not converting to a total remote work arrangement, it would make a lot of sense to create flexible hybrid — if not full-time — options for those who want to continue working remotely. To keep employees happy — and happier employees are more productive employees — organizations need to find ways that more meaningfully cater to their evolving needs. Employers will need to become more emotionally intelligent, rather than sticking with traditional norms. Those that can do this well — those who support and facilitate it — will set themselves up to be the organizations that people want to work for.

Why is there a need to rebrand the hybrid work schedule? What's the purpose?

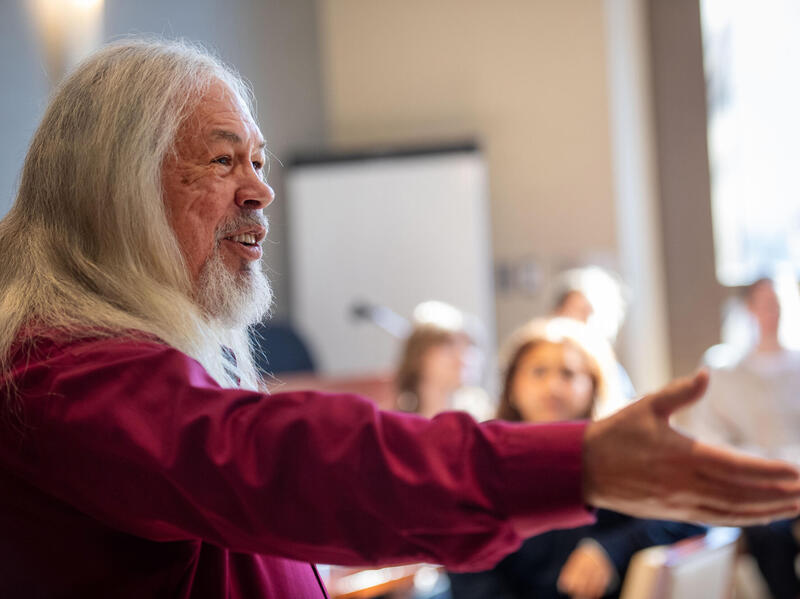

Caley Cantrell, professor and concentration chair, strategy and creative brand management, Brandcenter at VCU:

If some companies are choosing to adopt flexible/hybrid schedules, the current threshold for the majority of potential hires is “I'm going to have flexibility and choice — regardless of any future situation facing this company/organization.” I don't know if we'll always be wondering if a new variant is right around the corner, but in some sense a hybrid work schedule is becoming as important as a health plan — or possibly should be considered as part of a health plan rather than a job perk. Most folks would not want to give up health benefits and I believe that is what hybrid schedules are almost seen as.

I don't know whether we are “rebranding” (meaning, to me, “hybrid” seems like a definition or description, not a brand). However, by having a name or identity for your work plan/schedule/freedom of choice may be putting it on the same level as or a “kissing cousin” to the health (insurance) plan or “unlimited vacation days.” The hybrid work schedule is quickly becoming an expectation so why not brand it, especially if a prospective employee is choosing between two comparable jobs? Why do we need so many different brands of bottled water? Because.

Are employees going to be resentful about returning to the office?

Christopher S. Reina, Ph.D., executive director of the Institute for Transformative Leadership and associate professor in the VCU Department of Management and Entrepreneurship: Employees want it all! They want the flexibility of working remotely when it suits their schedule, and they want the option to connect with coworkers in the office when they crave human connection. Employees have become accustomed to having meetings canceled, agendas being shortened and/or adapted for modality pivots (i.e., in-person to remote), and they have also gotten accustomed to multitasking when on virtual calls (i.e., doing some monotonous tasks or filing emails while listening in on a Zoom call in which they are not the key presenter).

Attending in-person meetings again and showing “face-time” in the office to many now may seem like a burden, and one that diminishes their ability to advance family/home goals as well as work goals throughout the day (i.e., take care of small chores/tasks around the house as well as complete their workday).

When top leaders demand that workers return to the office four days a week as Disney's Bob Iger has done, employees likely immediately perceive a reduction in their autonomy as well as feelings that perhaps their competence or work ethic has been drawn into question. Autonomy and competence highly inform two core aspects of employee well-being, and being required to go back to the office on a set schedule thus produces palpable reductions in employee well-being.

How has remote work benefited companies and how has it been detrimental?

Reina: While there are many aspects of work that can be done remotely, there is no denying that something is lost in terms of depth or richness of connection when employees rarely spend time together face-to-face in person. However, it will be up to CEOs like Iger to redefine the post-pandemic workplace by finding new ways to instill a sense of autonomy and competence into employees' work lives if such demands on employees will be sustainable as far as retaining top talent who have grown accustomed to having the flexibility and autonomy that the switch to remote work has provided.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.