Dec. 4, 2023

‘Remember and Commit': School of Medicine researchers tackle obstacles and developments in HIV treatment

Share this story

When HIV/AIDS was declared an epidemic 42 years ago, patients had little hope. As AIDS, the illness caused by the human immunodeficiency virus, killed more than 100,000 Americans between 1981 and 1990, researchers raced to develop a treatment for the rapidly spreading disease.

Now, the fight against HIV represents the power of medical progress. Thanks to advancements in early detection and antiretroviral therapy (ART), the highly effective but costly medication regimen for the virus, what was once fatal in young, otherwise healthy people is now a treatable, chronic illness.

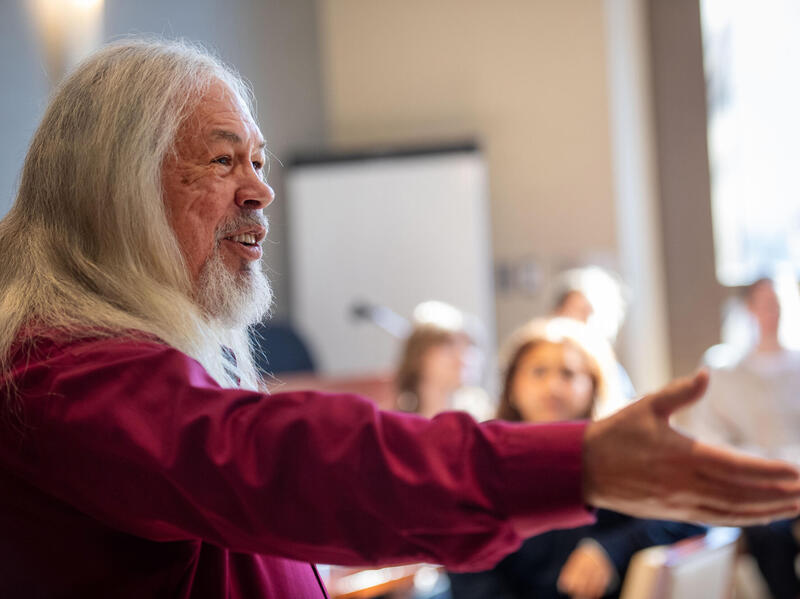

As more people with HIV live longer and healthier lives, medical professionals and scientists such as Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine’s Suzanne Lavoie, M.D. and Susie Turkson have turned their attention to other HIV-related challenges, including improving accessibility to treatment during pregnancy and understanding the impact of the virus on cognitive decline.

Eliminating barriers to care

Lavoie, a professor in the Department of Pediatrics and chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Children's Hospital of Richmond at VCU, joined the VCU faculty in 1993, near the peak of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and quickly realized the need for a specialized approach to treating children with HIV.

Lavoie said an early revelation for the team was that pediatric HIV was “primarily a family disease” — if a pregnant person who’s HIV positive is not on antiviral medication, the virus can be passed to the child in utero via the placenta, by exposure to HIV-infected blood during birth or through breastmilk. This motivated Lavoie to establish the first family HIV center in the region, where she and her team still treat patients today.

According to the CDC, pregnant HIV-positive birth parents on ART with a suppressed viral load have less than a 1% chance of transmitting HIV to their babies. Lavoie said it has been 10 years since a baby born at CHoR was infected with HIV at birth. However, she said CHoR has seen two instances of perinatal transmission and infection in the past two years, which she said emphasizes the need for continued commitment to education, awareness and health care access.

“HIV is a classic example of a disease that preferentially affects people who are in marginalized communities,” Lavoie said. “That includes those experiencing lower socioeconomic status and racial inequality, and things like language barriers and less access to physician hours.”

In this effort, Lavoie serves as the principal investigator of VCU’s Ryan White HIV/AIDS Clinic, a federally funded program that provides services to HIV/AIDS patients from marginalized communities. This clinic participates in the 340B Drug Pricing Program, a federal program created in 1992 that allows providers to purchase medications at a decreased price from manufacturers, which they can then dispense to patients cost-free or at a reduced price.

According to the Health Resources and Services Administration in 2023, access to free or reduced-cost drugs under 340B has resulted in almost 90% of RWC patients being virally suppressed, higher than 66% of the general population of those in HIV treatment.

“The goal is to decrease disparities in care, improve access and really ensure that people who are HIV-infected know their status and are able to get the medication they need to become undetectable,” Lavoie said.

VCU RWC is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ HIV National Strategic Plan to decrease new HIV infections by 90% by 2030, an effort Lavoie said is achievable with continued funding and dedication to addressing disparities in access and awareness.

“It’s a huge decrease, but we have the tools to do it,” Lavoie said. “HIV medication is excellent, and if we can get people to know their status and get on medication, that goes a long way in ending transmission.”

New solutions to persisting problems

Turkson, an M.D.-Ph.D. student, said she has always been interested in the brain and considered studying Alzheimer’s disease or traumatic brain injuries before finding her focus in chronic stress and brain function. This led her to?the lab of?Gretchen Neigh, Ph.D., in the Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, where she investigates peripheral biomarkers and their correlation with cognitive decline in women with HIV. ?

?“People with HIV are living much longer, but there are a lot of additional health conditions that we didn’t realize they were experiencing because in prior decades they weren’t making it to their 40s, 50s or 60s,” Turkson said. “They’re experiencing the health issues we’d typically associate with older individuals.”?

According to the National Institutes of Health, prior to the widespread use of antiretroviral therapy, HIV/AIDS often resulted in dementia as it progressed and attacked the brain. While?modern therapies?can prevent more severe premature cognitive decline, HIV-positive individuals can still develop HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders, or HAND. Symptoms include memory loss, irritability, depression and difficulties with attention and concentration.?

In Neigh’s lab, Turkson uses cognitive assessments and blood samples from populations of women with and without HIV to determine how changes in blood markers correlate to cognitive changes. The goal, according to Turkson, is to find a less-invasive way to predict disposition to cognitive impairment.?

“If this pans out, detection could eventually be as simple as getting blood drawn during a clinic visit and comparing cognitive function,” Turkson said. “Then we can start to target individuals at risk of decline with treatments and therapies. That may look like cognitive training, or lifestyle interventions.”?

Now in her sixth year of the Medical Scientist Training Program, Turkson said she is looking forward to translating the principles she has learned during her research to her medical practice.?

“The work I am doing right now is allowing me to look at clinical questions through a different lens,” Turkson said. “It allows me to get to the root of the problem and consider noninvasive ways to get to that root.”

This story was originally published on the VCU School of Medicine’s news site.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.