Oct. 17, 2025

VCU research in action: Teaching patients to take a deep breath

Share this story

Research in Action is a VCU News series that highlights how faculty, students, labs, community-engaged programs and other VCU initiatives are improving life through an unwavering quest for discovery.

In 2012, Meghan Varner felt like her body was falling apart.

“I had just begun my career as a physical therapist when I started to experience all sorts of interesting symptoms,” she said. “I came home exhausted every day. I felt lightheaded, I couldn’t think straight for periods during the day, and I struggled to keep up at work.”

After three years, Varner, D.P.T., was ultimately diagnosed with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, a condition in which the heart rate dramatically increases after a person stands or sits up. The result is often fatigue, poor exercise tolerance and brain fog.

When exercise, lifestyle changes and medications weren’t enough, Varner was introduced to a therapy – a controlled breathing technique, paired with heart rate variability biofeedback – to help manage her heart rate and shift her nervous system into a calm, healing state. Based on how much this technique alleviated her symptoms, she pursued further training in HRV biofeedback as a clinician to be able to offer it to her clients.

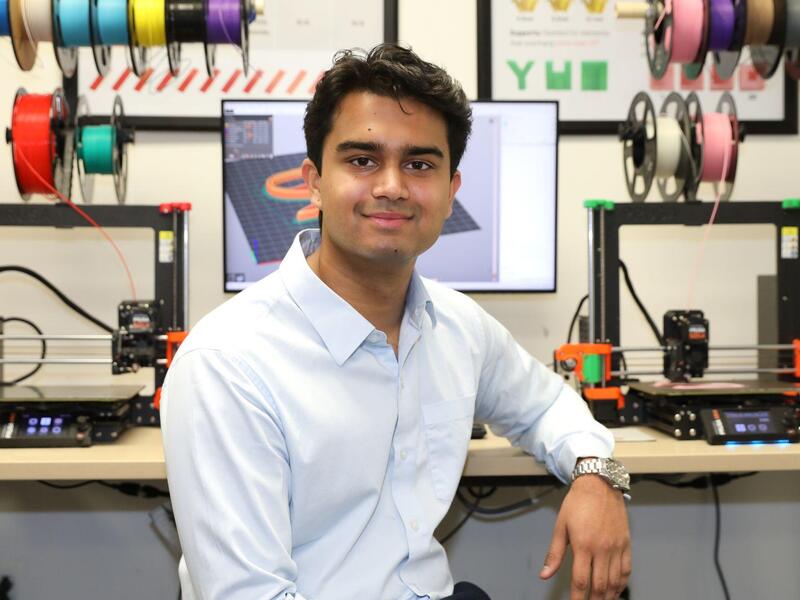

Varner is also part of a team of researchers and clinicians at Virginia Commonwealth University working to better understand and spread awareness of how HRV biofeedback can treat chronic conditions related to stress, fatigue and burnout. The overarching goal is to identify low-cost, noninvasive treatment options outside of surgery and pharmaceutics.

“We hope that this research opens more doors for those who have already exhausted their options for managing their symptoms,” said James Burch, Ph.D., a professor in the VCU School of Public Health’s Department of Epidemiology and one of researchers leading the work.

Stuck in threat mode

The team is focused on treating health issues connected to the autonomic nervous system, which plays a key role in how the body handles stressful situations.

During periods of heightened stress, the system’s “flight or fight response” is activated, causing blood pressure to increase while the heart beats faster and digestion slows. This system also helps the body return to a state of calm following such events. In this state of “rest and digest,” blood pressure decreases, the heart rate slows, and digestion starts.

Sometimes, though, the autonomic nervous system becomes disrupted, causing the fight-or-flight response to shift into overdrive. This can lead to poor sleep, fatigue, chronic pain, dizziness and trouble with memory or concentration, among other symptoms.

“There are a thousand ways that can cause a person to be stuck in persistent threat mode, whether that’s infections, injuries, emotional trauma, chronic stress or burnout from work,” said Raouf “Ron” Gharbo, D.O., a professor in the VCU School of Medicine’s Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation and one of the research leaders. “As a result, patients often feel stuck in a situation where they are hypervigilant and exhausted at the same time.”

Pausing to take a deep breath

There is growing evidence that patients can alleviate such symptoms by using a type of deep breathing exercise to control their heart rate. The HRV technique works by increasing the variation in heart rate over time, which increases cardiovascular capacity and resilience, or the body’s ability to manage stress.

“Deep breathing activates the vagus nerve, which carries signals between your brain, heart and other major organs in your body. It plays a major role in how the autonomic nervous system promotes relaxation, digestion, resilience and recovery,” Burch said.

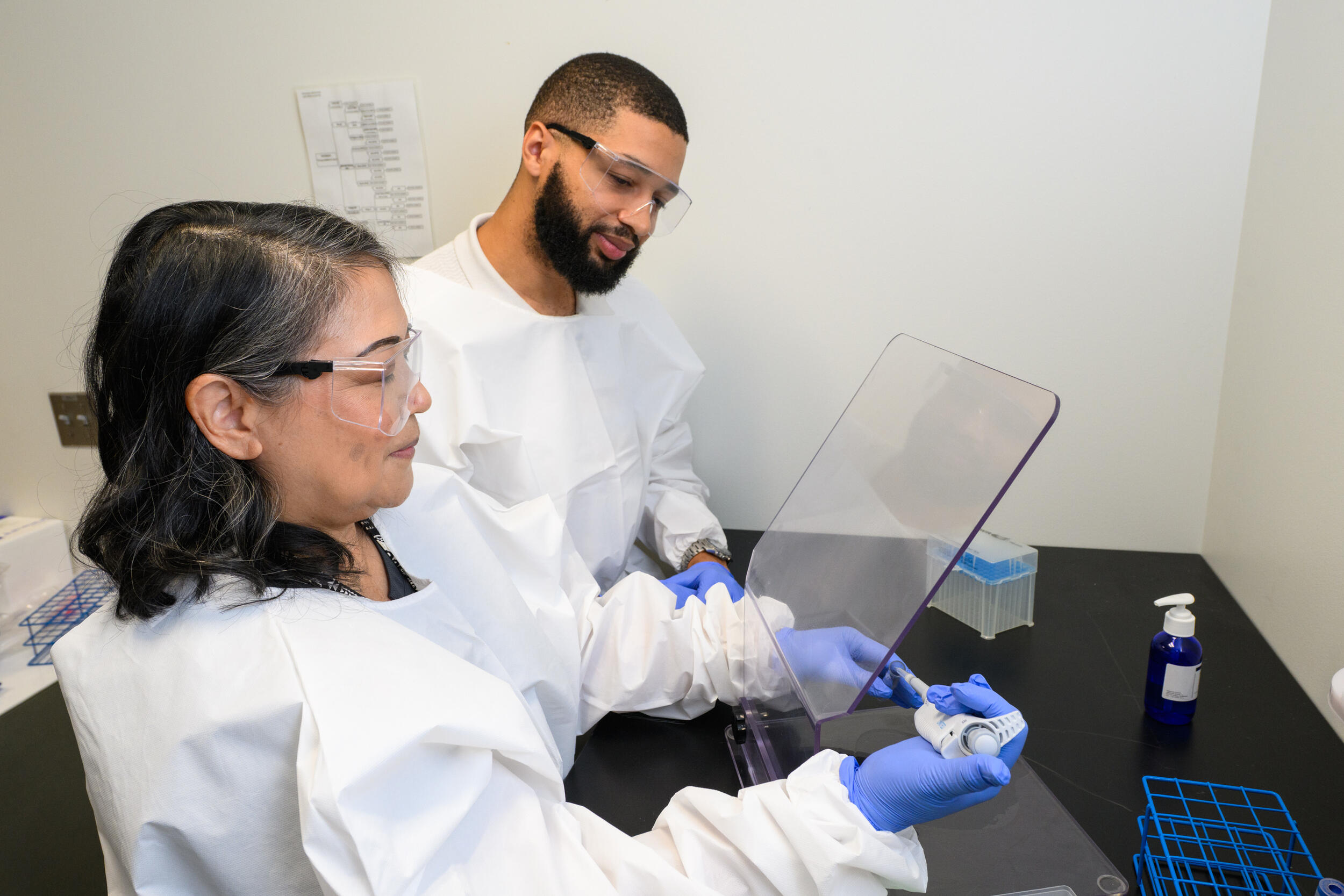

HRV biofeedback combines controlled breathing with real-time feedback on heart rate and breathing patterns. Patients are connected to heart rate monitoring devices and trained to breathe through their diaphragm in a specific pattern: typically around five seconds in and five seconds out. If done properly, the patient’s heart rate will become more variable, oscillating between higher rates while inhaling and lower rates while exhaling.

“I tell patients that we’re looking to create nice smooth ocean waves on the heart rate monitor,” Varner said.

By helping people control their breathing and, consequently, the variability of their heart rate, HRV biofeedback can reduce stress and improve heart health. The ultimate goal is for people to feel equipped to use this method to manage their symptoms, such as trying to get to sleep or dealing with stressful situations.

“When people learn this technique, they can use it whenever they need it. It’s not like they need a prescription for it,” Gharbo said. “You already have your diaphragm; you just have to learn how to use it.”

Advancing concussion research and military health

Studies have shown that HRV biofeedback can help with a number of health issues, such as chronic pain, PTSD and depression. But more research is needed to understand what other conditions may also benefit from this treatment.

Gharbo and Burch have played key roles in bringing HRV biofeedback research and clinical care to VCU since their arrival in 2021.

Their research team is currently assessing whether HRV biofeedback could be an effective therapy for veterans and service members with lingering health issues from concussions. Supported by a $6 million grant from the Department of Defense, the four-year HERO study will evaluate whether HRV biofeedback helps address long-term symptoms, such as difficulty sleeping, headaches and concentration issues.

Participating veterans and service members will attend six weekly HRV biofeedback sessions, as well as engage in controlled breathing practices twice a day on their own time. To compare HRV biofeedback against current treatments for post-concussion symptoms, another group of participants will receive information on how to manage stress and concussion symptoms while improving mental well-being.

Military service members face an especially high risk of concussion from blasts or other service-related injuries. Jennifer Weggen, Ph.D., a clinical research scientist with the Department of Epidemiology who is involved in the work, is also a Navy veteran, and she said the research is an extension of her service.

“I never had to go to war or fight in combat when I was in the military, but I know a great number of people who did,” she said. “Being involved in this research is my way of giving back and helping people recover from trauma.”

Expanding HRV biofeedback’s clinical impact

The researchers are also exploring the treatment’s potential for other groups facing high rates of chronic stress and burnout. The team will soon launch a pilot study, called SHIFT, to assess the impact of HRV biofeedback sessions via telehealth for first responders – including law enforcement officers, firefighters, emergency medical technicians and paramedics – who often face long shifts, sleep deprivation and traumatic situations.

The research group also launched an initiative aimed at training health care workforce members in providing HRV biofeedback to their patients. In the HRV STAR study, through four to six weekly sessions, clinicians at VCU Health are learning the skills and receiving technical support to bring the therapy into their own practices. The training program has brought in a wide range of health professionals, including physical therapists, nurse practitioners, social workers and psychologists.

“Our goal is to help as many people as we can, but our team can only see so many patients,” Burch said. “We want to show that this form of treatment can easily be put into your toolbox for lifelong health.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.