Jan. 11, 2019

The centuries-old practice of exorcism is on the rise. Why now?

Share this story

The cover story of this week’s London-based Catholic Herald explores a surprising surge in exorcisms — the act of expelling demonic forces from a possessed person — throughout the world, including in the United States.

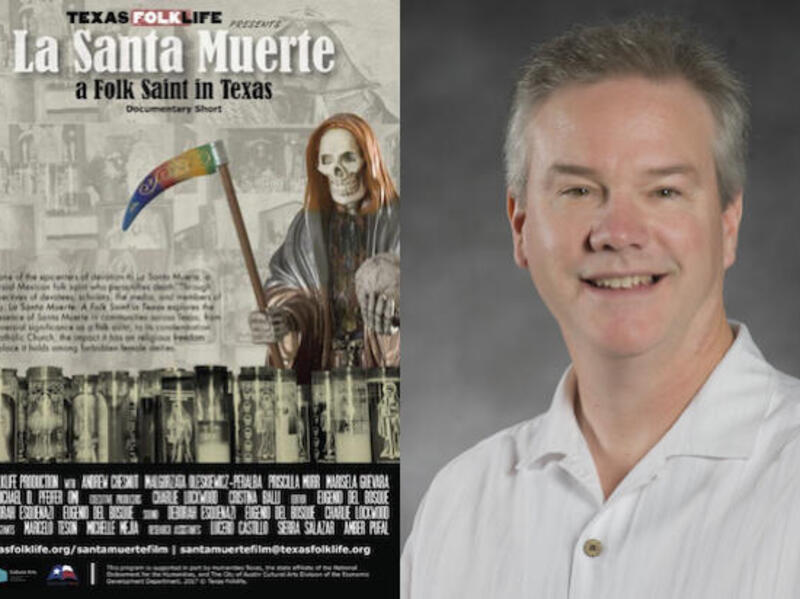

The article, “Driving out the Devil: what’s behind the exorcism boom?,” is co-authored by R. Andrew Chesnut, Ph.D., the Bishop Walter F. Sullivan Chair of Catholic Studies and professor of religious studies in the School of World Studies in the College of Humanities and Sciences at Virginia Commonwealth University, and Kate Kingsbury, Ph.D., an anthropology professor at University of Alberta.

Chesnut, author of “Born Again in Brazil: The Pentecostal Boom and the Pathogens of Poverty,” “Competitive Spirits: Latin America's New Religious Economy” and “Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint,” discussed the article and the resurgence of exorcisms with VCU News.

In your article, you describe not only how Pope Francis has personally performed an exorcism, but he also convened an exorcism workshop at the Vatican last year that was attended by 250 priests from 51 countries. Do you think people would be surprised to know how mainstream the practice of exorcism has become?

Yes, I think most Americans and Europeans, in particular, would be very surprised to know how widespread the practice of exorcism has become over the past few decades. Many Americans and Europeans of my generation were influenced by the seminal film, “The Exorcist,” which presents demonic deliverance as an extraordinarily rare, almost covert, Catholic rite. As my co-author Dr. Kate Kingsbury and I point out in the article, exorcism has become so commonplace today that some exorcists even expel demons remotely, via cell phone.

What do you see as the driving factors behind this resurgence?

One of the most important factors driving the exorcism boom is the Pentecostalization of Christianity, especially in the Global South. Pentecostalism has mushroomed in Africa and Latin America since the 1970s to the extent that Brazil is now home to the largest Pentecostal population on Earth. With its emphasis on the spirits, both the Holy Spirit and demons, Pentecostalism is the branch of Protestantism that thrust exorcism to the front and center of its practice in the 1970s.

In order to compete with the dynamic Pentecostals, especially in Africa and Latin America, the Catholic Church has had to step up its exorcism game, thus the recent Vatican conference and flurry of training courses for clergy interested in becoming exorcists.

On the demand side, I don't think much has changed as there has always been significant desire for both spirit possession and expulsion among large sectors of the global Christian population, particularly in Latin America and Africa where pre-Christian indigenous religious practices tended to center on spirit possession.

Your article notes that different regions of the world believe people are possessed by different entities. In Brazil and the Caribbean, you write, possession is attributed to liminal trickster spirits of Candomblé, Umbanda and other African diasporic religions. In Mexico, it is often attributed to the folk saint Santa Muerte. In the United States and Britain, the belief is people are possessed by demons. What links all of these possession beliefs?

In the cases of African religions, African diasporic faiths and Latin American folk saints there is a literal demonization of their spirits by Pentecostal and Catholic exorcists who claim that they are all evil regardless of their identities in their native traditions. For example, many devotees view Santa Muerte as a powerful curandera, or healer of illness.

In stark contrast, Catholic exorcists in Mexico see nothing but the satanic antithesis of Jesus Christ in the figure of the skeletal Grim Reapress that is Santa Muerte. Apart from immigrant churches in the U.S. and Britain, the demons that possess Americans and the British are often identified as “vices,” such as alcoholism and gambling. The commonality here of course is a shared belief in the spirit world inhabited by both the Holy Spirit and demons.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.