Feb. 19, 2020

‘They knew what was right’: A restaurant sit-in and the story of the Richmond 34

Share this story

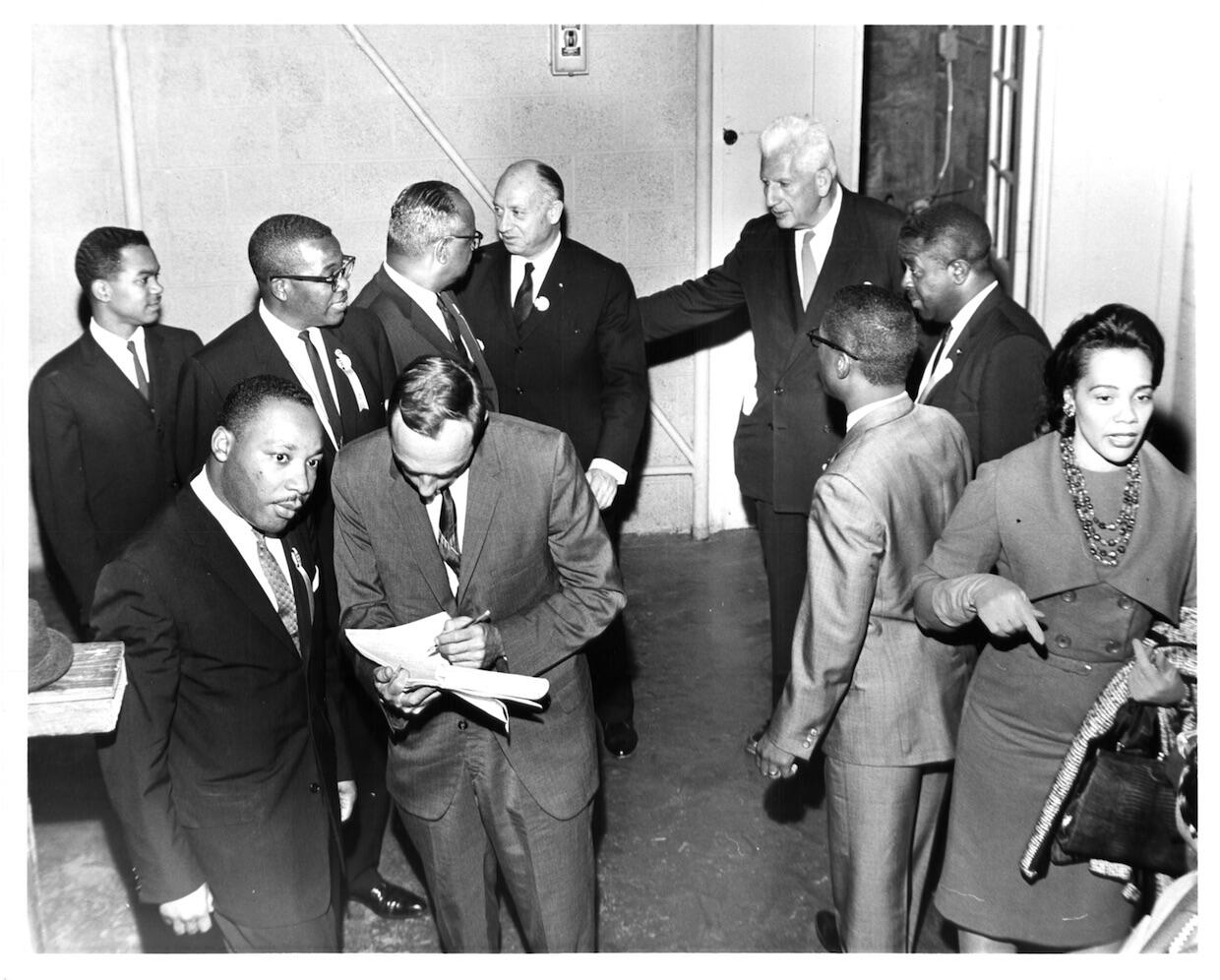

On Monday, Feb. 22, 1960, 34 Virginia Union University students were arrested at Thalhimers department store on Broad Street for refusing to leave its Richmond Room restaurant. The sit-in was just one of many that hundreds of students were taking part in that day in a stream of protests aimed at challenging the discriminatory practices that barred African Americans from certain Richmond businesses. The arrests and the impact of the student sit-ins helped to change those discriminatory practices.

“The Richmond 34 and the Civil Rights Movement” is being released this month to coincide with the 60th anniversary of those protests. The book was written by Kimberly Matthews, Ph.D., a professor in VCU LEAD, a living-learning program at Virginia Commonwealth University, in collaboration with Raymond Pierre Hylton, Ph.D., a history professor at Virginia Union University.

“The Richmond 34,” which provides a pictorial history of developments that led to the arrests, is Matthews’ second book in Arcadia Publishing’s Images of Modern America series. Her first was “The Richmond Crusade for Voters.”

Matthews shared with VCU News some of what she learned about the Richmond 34 and their context within the civil rights movement.

Why was it important to tell this story and tell it visually?

It was a little-known story because protests that happened after this became shockingly violent. [In Richmond] it was a very peaceful protest, and before some of these others. However, it became overshadowed because of some of the more violent arrests and protests that happened deeper in the South. The story kind of gets lost, but it was a huge deal at the time. And that's the reason for the book, to chronicle that. The chapter on Virginia Union [describes how] Union has always been a place where students were able to express themselves and fight for rights. It wasn't a surprise that the VUU students were a part of that, but then the story got lost. So that was really the catalyst for me wanting to work on this book and tell their story.

What did you uncover visually that you felt was important to tell in this format?

I love this format because you're able to see the people you're talking about. You're able to see the places that we're talking about. It's not just 34 names on the sheet, these are actual people and you can look at them and you can [make a connection].

These are the ages of the students I teach. Thinking about the sacrifices at that young age and what a huge event that was, I just loved the pictorial histories because people are able to connect. They can say, “I can drive down that street,” or “Yes, that was the Eggleston Hotel or the Hippodrome Theater or Broad Street.” Because when people think about the march, you can visualize going up Lombardy to Broad Street. And that's not an easy walk. It's not a quick walk. But they did it.

Can you share the origins of the Richmond 34 and activism at Virginia Union University?

Virginia Union University started as an educational institute in the former Lumpkin’s Jail building, and it had the feel of wanting to empower African Americans. They did that through education. But as the years went on, there was a lot of activism as well, looking at injustice in the city.

As a [historically black] university in the capital of the Confederacy during the Civil War, there were things they had to combat and overcome, so empowerment was part of the goals with Union, not just the educational part. The Richmond 34 had people come down and teach them [about protesting, effective activism and nonviolence]. The president and faculty knew and supported them. The VUU leadership didn't say, “Yes, go do it.” But they didn't say, “Don't go do it.” The support that they had from staff, faculty and administrators helped. They felt like, “OK, this is something we can do and we should do. We have support. And let's do it.”

There is lots of overlap with the Richmond Crusade for Voters movement. Most people were involved in the crusade as well as the NAACP. Those adults helped train some of the students for the sit-ins. Union, during the civil rights era, was very heavily activist-based. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. actually had some connections with people here in the city as well as at Union. [One of the Richmond 34 arrested], Elizabeth Johnson Rice, actually tells a story about how King came down and helped train students.

Did the students have a history of activism or was this their first foray?

I think for some, it may have been their first, but for a lot, there was activism at home as well as at school. I think a lot of it was instilled in them earlier, before they even probably came to Union, that they're going to fight for justice in some form or another. This came up and they're like, “OK, this is downtown, we're invited, but not quite invited. And this is something that could have long-lasting impact as well.”

When you start hitting people in their pocketbooks, that's when change starts. Sitting in at Thalhimers was not an accident. That was all planned because Thalhimers was the leading department store downtown at the time. So hitting them in the pocketbook really changed things.

Is there a connection to the subject you teach — leadership — and the way you approach your research on leaders?

There's really a leadership thread through both of these books that people took leadership of their own future and decided to make a change. These weren't easy changes because this was in Virginia in the Jim Crow South, with a lot of danger involved in making these decisions. With this group, they were students so they had a lot to lose as well. Not just that, they could have been expelled from school.

They were arrested, but it could have been a lot worse and knowing that they still did it. They knew what was right and what was wrong. But because of the circumstances, because of the context and situation, these laws had been in place for years. So just taking the risk is huge. I'm pretty sure they didn't realize what impact they had and that they were leaders and that this would change the face of Richmond. They probably thought, “OK, great, this is what we want.” Other protests around the state, and the country as well, led from that.

Who were the key figures?

Rice was one, but this guy on the front cover, Leroy M. Bray Sr., as well. This is really the iconic photo. He was the key figure really. I was just so glad to get this one from The Valentine museum. This photo really speaks to me because he looks like a grown man, as if he could have a family, and not the student he was. He's dressed up with a tie on and a suit. Typically, on campus, they dressed up. But when they were leaving campus, they dressed up as well. Because of the sentiments of Jim Crow, you had to look like you belonged. I just look at that and I think about my students, who are also 18-, 19- and 20-year-olds. I would say Bray was the face.

What happened to the students once they were arrested? And how did that affect them afterward?

They had a fine of $20. It was a trespassing fine. Through the appeals process, it went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The student named was Raymond B. Randolph Jr. versus the Commonwealth of Virginia. It was Raymond B. Randolph Jr. et all. It went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and was overturned in 1963. This was three years after the event.

I would say Randolph was a huge figure because he led the charge with the lawsuit. But you had athletes, you had students who were interested in pursuing politics and history. I think it was their status on campus that allowed them to take the lead.

Another key figure I would say would be Dr. Anderson Franklin. He went to get a passport in 2018 and was told, “No, you have charges still on your record.” So it was overturned, but it stayed on their records. They went to court last year to get all of that expunged from their records.

Can you say more about the impact of the sit-ins and the Richmond 34?

The desegregation did happen and it was because of the economic impact. They continued it beyond that one day. I wouldn't say that people were out there daily. The campaign for human dignity took many forms. This was just one form that hit them in the pocketbooks economically. That was probably one of the major factors of the [store owners] desegregating lunch counters. There were protests going on around Thalhimers, Miller & Rhoads and some of the other shops. What would happen was that the students would rotate. Some would stay at the counter, some would go out and protest. It just so happened that these 34 were the ones who were sitting at the Thalhimers lunch counter at the time. So they were arrested. But there were many other students. It's estimated between 200 and 300 students actually made the walk and were protesting downtown. It was part of a yearlong, or yearslong, effort that lasted to 1963. It was strategic.

Did you learn anything that surprised you about the Richmond 34, Virginia Union University or attitudes at that time?

Going on the journey, attaching names with photos and their experiences and then realizing that these 34 students who were arrested, and the 300 other students, had the bravery to take the risk for something they knew was right and knew that not only they could benefit from, but generations after them could benefit as well. … I would love to use them as examples for my students. To tell them, you are a student but you have an impact. As a group together, they had an impact on Richmond and how it was run at the time, what certain people could do and others couldn't.

|

Anything you would classify as a discovery?

I think that it affected people in different ways. Barbara Thornton Nero had to leave Union. Her father’s business had to close and they had to go out of state. She wasn't expelled, just the impact of the walk. Her father's business, which was lawn maintenance, suffered and she and her family had to move.

I think it's important to go back to tell the story that it wasn't just, “Oh yes, it's great. You all sat in and then there were these positive outcomes.” It took time. And for some people, it dramatically changed them.

That was one reason we couldn't find a yearbook photo of Thornton Nero. Our mindset is that these students were out there, they were changing the world, changing the status quo here in Richmond, Virginia. But it wasn't a positive impact for everyone and it wasn't seen as positive by everyone as well.

My mindset going in was that these were heroes. She’s one of the 34, so why would her father's lawn business be affected in a negative way? Now you think about how when people protest, and it's a positive thing, people will go to the store in support. But that didn't happen for everyone.

What about the impact the experience had on the students and their careers?

People graduated and went on and it was this huge thing for a while. But it’s gotten overshadowed. I think the major impact has been in wanting to celebrate the event and looking back at the courage they had to exhibit.

People will talk about being civically active, politically active and so forth, but never put themselves out there like they did. The experience really instilled in them the activism spirit, but also wanting to continue their educational path. They felt they'd be more impactful, at different levels and in different arenas, being role models for people. I think that also contributed to their determination to continue their education and to move forward with positive careers.

I know for me, I wanted to contribute to the legacy of the Richmond 34 by telling their story as well. The Richmond 34 had an impact on changing not just Richmond but Virginia with their laws and segregation. That one act, even though it was a huge act, it was one act with these students and on this day really had such a huge impact on the state.

Because of people that they will never meet or never know, because of them they could go to the lunch counter now and actually have a seat. So having that vision that was larger than themselves, I think, is the legacy.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.