Feb. 15, 2010

VCU Rice Center Part of Effort to Restore Atlantic Sturgeon to the James River

Share this story

On a chilly, windswept day on the James River recently, Virginia Commonwealth University’s Rice Center joined with community and corporate partners to embark on a landmark project to restore the Atlantic sturgeon to the James River.

If the project succeeds, it could be a bellwether signaling that the ecosystem of the James, and perhaps the entire Chesapeake Bay, is taking a turn for the better.

The ambitious effort began with piles of rocks.

The rocks – more than 2,000 cubic yards of them donated by Goochland County-based Luck Stone Corp. – were dropped from a barge into the James River near Presquile National Wildlife Refuge in Chesterfield County to form a 300-foot-long artificial sturgeon reef, the first of its kind for the Chesapeake Bay watershed and the entire East Coast.

It is hoped that the Atlantic sturgeon, a fabled prehistoric species of fish that has been sighted in the area, will spawn and deposit their eggs on the reef. Sturgeon merit an historic footnote in Virginia history, because they are credited with being a critical food source that helped the Jamestown colonists survive when there was little else to eat.

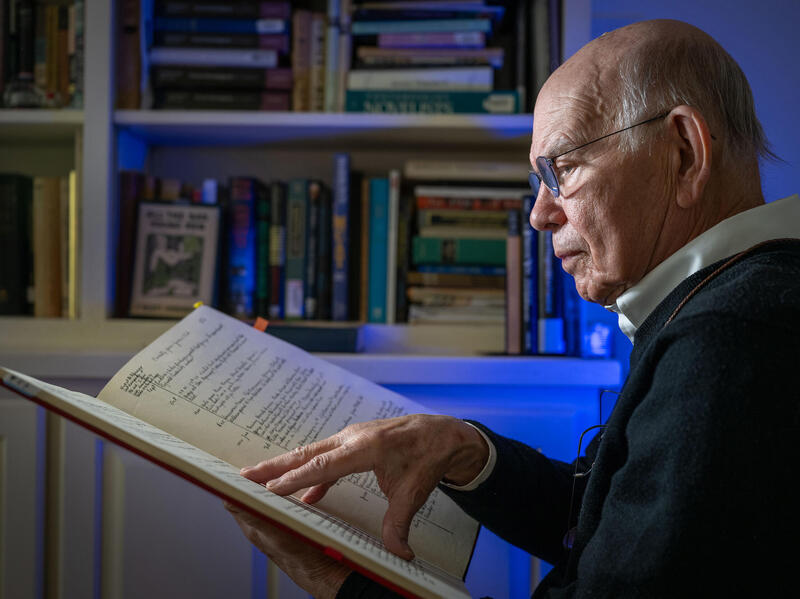

Greg Garman, Ph.D., director of VCU’s Center for Environmental Studies and research director of the Rice Center, watched intently from a small boat as the reef was being formed.

Keeping watch from another location were Chuck Frederickson, lower riverkeeper for the James River Association, and Mark Williams, environmental manager at Luck Stone Corporation.

The project took four years to coordinate and is a partnership between VCU, the James River Association -- a 3,000-member conservation group -- Luck Stone and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, which assisted with a $50,000 grant. They are all part of a larger Virginia Sturgeon Restoration Team.

The sturgeon itself is one of the most exotic fish on the planet with bony, armorlike plates instead of scales. The fish easily can grow more than 10 feet long and weigh more than 300 pounds and can live more than 50 years.

Sturgeon have dwindled precipitously near extinction in the James River because of overfishing and habitat changes brought on by development and by agricultural runoff that created silt, which smothers sturgeon eggs.

If sturgeon can breed themselves back into large numbers starting from the artificial reef, their return could spark a revival of commercial and recreational fishing, tourism and perhaps even a caviar industry – from sturgeon eggs.

That doesn’t mean that caviar will be on the menu for VCU’s Shafer Court and Larrick dining centers anytime soon.

“The potential is certainly there to have a caviar fishery in the James River, but we’re at least 20 years away from that,” Garman said with a laugh.

Right now, everyone’s eyes are on the science.

If all works well, there will be a lot to be learned about habitat restoration, the migration of sturgeon from the ocean to fresh water, the ecology of the James River and the Chesapeake Bay, and how science can work in communion with nature to foster a better environment.

Happily, VCU is strategically positioned as both a major contributor and a beneficiary of all that might occur.

“Because the Rice Center is in the middle of the sturgeon’s spawning habitat, VCU is in a great position to take a lead role in this restoration effort. We’ve got the facilities, we’ve got the folks and just geographically we’re in the perfect place to do this work,” Garman said.

Perfect for the science and perfect for being in a front-row seat for the often spectacular antics of sturgeon in the wild.

Garman said it is one of nature’s great moments to be on the Rice Center’s pier in Charles City County and experience the thrill of watching a sturgeon – the size of an extra-large sumo wrestler with the leaping ability of a ballet dancer – explode out of the water full-length and become airborne.

“This is one of the most exciting critters I’ve had a chance to work with. It really gets the adrenaline going,” Garman said.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.