June 18, 2015

Globalized health: VCU students lead the charge to deliver needed care in developing countries

Share this story

Note: This article originally appeared in the spring 2015 VCU Alumni magazine. Active, dues-paying members of VCU Alumni receive a subscription to the magazine as a benefit of membership. To read the whole magazine online, join today! For more information, visit vcualumni.org.

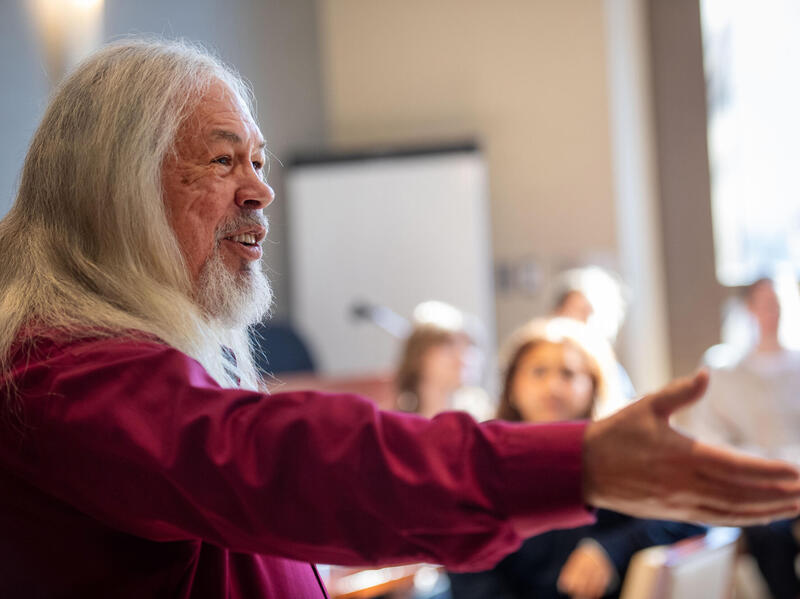

It was nearing evening in a remote mountain village in southwestern Honduras when Zack Lipsman, M.D. (M.D. ’15/M), spotted a young girl waiting with her friends outside of the makeshift clinic where he had been working all afternoon. He was there on a 10-day service trip in June 2012, the summer after his first year of medical school at Virginia Commonwealth University.

“She looked kind of sad and lost,” Lipsman says. He went outside with a few other medical students to ask if she needed to be seen by a doctor. As he got closer, he realized why she was there.

“When we saw she was pregnant, everyone kind of just froze for a minute,” he says. “She was so young, and she clearly had no concept of what her future would be like. We had to huddle together to think about how we could best help her.”

The 13-year-old was late in her second trimester and had never been seen by a doctor. The students arranged for her to have her first prenatal screening the next day.

“That was a turning point for a lot of students in realizing the gravity of what we were doing there,” Lipsman says.

Since 2006, VCU School of Medicine students have been traveling to Honduras to provide direct medical care and health care education to underserved populations in some of the poorest areas of the country. The Honduras Outreach Medical Brigada Relief Effort (HOMBRE) is one of many university-affiliated organizations that offer students international health care service opportunities. During the trips, students apply what they’ve been taught in the classroom to a clinical setting and learn invaluable lessons from the communities they serve.

“VCU faculty and students are not content to just theorize about making a difference. They want to roll up their sleeves and have a direct impact on what they see as crucial issues.”

“VCU faculty and students are not content to just theorize about making a difference,” says McKenna Brown, VCU Global Education Office executive director. “They want to roll up their sleeves and have a direct impact on what they see as crucial issues.”

University support through the Global Education Office and individual schools helps to fund a portion of the outreach trips, but most of them rely on donor gifts either through specific scholarships or to individual students to cover expenses such as flights, accommodations and medical supplies.

Brown estimates that more than a dozen noncredit international service trips take place a year, often supported by student-run organizations with representatives from both campuses at every level of the university.

“Global health is an issue of growing importance at VCU,” Brown says. “We have a student body that is exceptionally committed to community engagement.”

Vital checkups

No roads led to the village where Lipsman and a team of medical students and faculty would be volunteering on that June day, so they departed from Pinares, Honduras, before sunrise to hike through the mountains for three hours, arriving by late morning at a one-room school more than 4,600 feet above sea level.

“All of us brought backpacks,” Lipsman says. “We would fill them with as many supplies as we could carry.”

When they arrived, they set up eight stations where they checked vital signs such as blood pressure and hemoglobin levels. They also distributed anti-parasite medication and put dental varnish on children’s teeth.

During the 10-day trip, School of Medicine students treated about 350 children in seven villages. Students and faculty also volunteered in Pinares, where they saw patients at a 1,000-square-foot cinderblock clinic for conditions ranging from musculoskeletal complaints to acute appendicitis.

“You can’t go down there and just administer medicine,” Lipsman says. “You need to develop relationships with the folks in these villages.”

The School of Medicine organizes three trips a year to Pinares, where medical and pharmacy students and faculty volunteer on public health initiatives geared toward improving villagers’ quality of life. HOMBRE also hosts clinics in other areas of Honduras, as well as Peru and the Dominican Republic. The dean’s office at the School of Medicine helps pay for a portion of the students’ airfare to the sites, but most of the funding comes from donations to HOMBRE and personal contributions. The donations help pay for medications, equipment and educational materials.

Now in his fourth year of medical school, Lipsman returned to Pinares for eight days in February to volunteer at the clinics.

“I hope to involve myself in a project that is set up similarly to this as a doctor, where you can be a part of a team that goes down multiple times yearly to an established site,” he says. “For a lot of these things to be successful, they have to be sustainable.”

Sustained care

Success comes naturally to the VCU School of Dentistry’s Jamaica Project, which has hosted a clinic near Clark’s Town, Jamaica, for almost 30 years.

Since April 1986, fourth-year students and faculty have gone to a farming community near the Trelawny sugar belt every year to provide cleanings, extractions, restorations and oral health education.

Through the Jamaica Project, students see about 1,400 patients a year at a 500-square-foot minimal health clinic and at elementary schools throughout Trelawny Parish. Students pay for their own airfare and meals. In 2012 the Robert F. Barnes Jamaica Fund was established in honor of the former faculty adviser to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the project. The money from that fund is used to purchase portable dental equipment. The program also relies on individual donations to help pay for supplies, such as toothbrushes.

“You don’t realize how important it is to donate until you go down there and see what the people don’t have,” says Virginia Beach, Virginia-based dentist David Mueller, D.D.S. (D.D.S. ’90/D). In addition to donating financially every year since 1988, Mueller often travels to Jamaica with the school to volunteer his time. “When you go to the market and the cost of a toothbrush is equivalent to the cost of a week’s food, it’s easy to see which decision they make.”

“When you go to the market and the cost of a toothbrush is equivalent to the cost of a week’s food, it’s easy to see which decision they make.”

After the free dental exams, every patient receives a toothbrush, toothpaste and floss.

“There would be a line of people outside every day,” Courtney Schlenker, D.D.S. (Cert. ’10/M; M.S. ’11/M; D.D.S. ’15/D), says of the clinic that was housed in a rural area outside of the city. “They would literally wait all day until they could be seen.”

The recent graduate extracted about 80 teeth during the week she was there in October 2014.

“At school you might extract 10 teeth in four years,” she says. “Our confidence level for performing extractions is a lot higher than students who don’t do these projects.”

Schlenker recalls a 17-year-old patient who waited outside the clinic all day just to thank her for extracting a few teeth.

“That he would wait for hours just to thank me for getting him out of pain shows how grateful they are,” she says. “The trip reinforced the importance of giving back to people who don’t have the access to care that they need.”

Gratuity included

During a 2014 trip to Guatemala with Nursing Students Without Borders, Katherine Connell (B.S. ’15/N) was inspired by the thanks she received from the community members she was there to serve.

A little more than a year before Connell went to Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, the area had been hit by a 7.4-magnitude earthquake that killed 11 people in the mountain valley city and destroyed many homes.

Connell recalls one family in particular whose home was buried under a mudslide soon after the quake.

“They lost everything,” she says. The 22-year-old was there on a joint humanitarian aid trip between NSWB and the Highland Support Project, a Richmond, Virginia-based nonprofit organization.

In addition to conducting health screenings and hosting health care education workshops, students help build stoves for local families so that they would have a safer, cleaner method for cooking meals.

“The stove idea originated because families in the Highlands are used to cooking on open fires, so kids would get badly burned, and people would develop respiratory illnesses,” Connell says. “In a way, the stove is a preventative health measure.”

Connell helped to build a stove for the family who had been hit with the earthquake and mudslide. She worked in the family’s home for two days, assembling the stove from cement blocks, bricks and rocks.

“They were so grateful we were there,” she says. “It made building the stove that much more important for me. I felt like I gave something that is going to help that family for years to come.”

Donations to the university’s NSWB chapter help pay for the stove-building supplies as well as for medical supplies that students use during health screenings they host throughout the week.

“It’s a wonderful way for the students to be exposed to global health,” says former NSWB faculty adviser Victoria Menzies, Ph.D. The associate professor in the Department of Adult Health and Nursing Systems at the VCU School of Nursing has donated financially to the organization in past years in addition to helping organize the trips. “I believe in students giving back,” she says. “Who knows what will come of their careers because of that experience.”

During the health screenings, Connell would check weight, height and glucose readings for the community, in which diabetes and hypertension are common health concerns.

“Tortilla and corn are the staples of their diet because that’s what is available,” Connell says, adding that a swath of new convenience stores has contributed to the already unhealthy diet in the community. “It’s cheaper to buy a Coke than grow a cabbage in the field.”

Practicing nursing in a community and seeing how the patients live underscored Connell’s commitment to preventive health and provided her with a perspective beyond the confines of a classroom or hospital.

“It’s OK to sit down and have a conversation with your patient,” she says. “In the hospital we get used to doing the same assessments and asking the same questions. When you’re in the community, you see things you wouldn’t otherwise consider.”

Beyond the lab

Biomedical engineering graduate Shruthi Muralidharan (B.S. ’15/En) credits the experience she had working in the field, and out of the classroom laboratory, for helping her develop real-world skills.

While working at a small, rural hospital outside of Esteli, Nicaragua, last summer, Muralidharan encountered an aging electrocardiogram machine that needed to be repaired.

The former president of VCU’s Engineering World Health chapter worked with a fellow student volunteer to open the machine and examine the connections. She discovered that one of the machine’s leads had a severed point, which she fixed by salvaging a replacement part off an old, unused EKG. Muralidharan also noticed that a lead that connected to a patient’s chest was not staying attached, so she retrieved an old blood pressure cuff from the hospital maintenance staff and used it to fashion a makeshift connector.

“I learned how to troubleshoot and not be afraid to look into the machine,” Muralidharan says. “When you’re here in lab and you’re working on different circuits, if you don’t get it you can ask the teaching assistant. There, you have two months to work with something, and if you don’t fix it, they’re stuck with nonfunctional equipment.”

Muralidharan spent her first month in Nicaragua taking Spanish and engineering classes in Granada and volunteering at the city’s hospital once a week, where she would do preventive maintenance and repairs on the hospital’s mostly donated equipment. During the second month, she worked more independently at a remote hospital in Esteli, repairing much-needed medical equipment and training doctors to operate the machines.

“We would sit at Wi-Fi cafes on days off and find manuals for specific machines that we’d translate into Spanish,” Muralidharan says. “The doctors were grateful for that. They said it helped a lot because they could understand how to use the machine properly.”

Muralidharan, who graduated in May, hopes to work at a medical device company. She believes that direct experience she got from working on machines at the hospitals will help her feel more confident as a young engineer.

“I feel like I’m more courageous to be able to troubleshoot and take on problems head on,” she says.

Committed to serve

In addition to donations from individuals and businesses in the Richmond community, the Global Education Office helps to fund international health service opportunities for students through various grants, including the Quest Global Impact Award and the VCU Global Health Fund. The money raised from the awards helps enhance the recruitment of students into global health research and practice careers by providing them the means to attain international clinical or other field experiences.

As a research university with a commitment to advancing human health, VCU makes it a priority to help fund them.

“Our responsibility as a university is to prepare the students of Virginia for success in an increasingly globalized world,” Brown says. “Even if a student never intends to leave their home community, having the knowledge, skills and experiences to navigate across differences in language and culture is going to give them a competitive edge and prepare them for greater professional and personal success.”

Featured image at top: Zack Lipsman, M.D. (M.D. ’15/M), checks the eyesight of a young boy during a 10-day service trip to Honduras.

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Thursday. VCU students, faculty and staff automatically receive the newsletter. To learn more about research taking place at VCU, subscribe to its research blog, Across the Spectrum at http://www.spectrum.vcu.edu/

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.